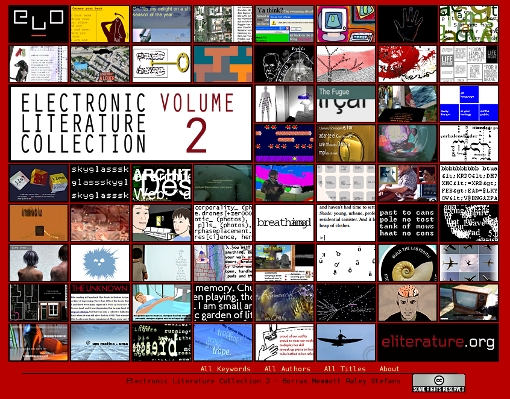

##### The blog edition of my presentation at the Electronic Literature Organization’s ELO_AI Conference, Brown University, 5 June 2010

The process of writing and programming the first two full-scale interactive fiction pieces in the new system I have been developing, Curveship, has been a part of my poetic practice that I have found interesting and has also been a useful activity from several perspectives. Here I focus on the project _Adventure in Style_. I will also mention _The Marble Index_, a project that contrasts with _Adventure in Style_ in an important way. These two pieces, still in progress, are initial explorations of the potential of Curveship and of the automation of narrative variation. My hope has been that these two games will serve as provocative interactive experiences, whether or not those who interact with them are interested in Curveship as a research project or as a development system. Of course, it will be very useful if they also serve as demonstrations of how Curveship works. I have, additionally, used these two projects to help me determine what additional development is critical before I release Curveship.

While Curveship has functioned as a research system for several years and has been previously discussed from the standpoints of computer science, artificial intelligence, and narrative theory, this is my first attempt to discuss the specific pieces of interactive fiction that were conceived as aesthetic projects, rather than primarily for research or demonstration purposes.

#### Curveship

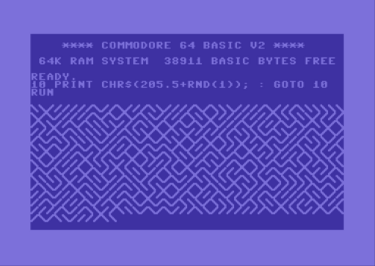

The system used to implement these pieces, Curveship, is an interactive fiction development system that provides a computational model of a physical world, as do existing state-of-the-art systems such as Inform and TADS. Curveship does something significant that other systems do not: It allows author/programmers to write programs that manipulate the telling of the story (the way actions are represented and items are described) as easily as the state of this simulated world can now be changed. It has been straightforward to simulate a character and to have that character move around and change the state of the world. In addition to this, Curveship provides for control over the _narrator_, who can speak as if present at the events or as if looking back on them; who can tell events out of order, creating flashbacks or narrating what happens by category; and who can focalize any character to relate the story from the perspective of that character’s knowledge and perceptions.

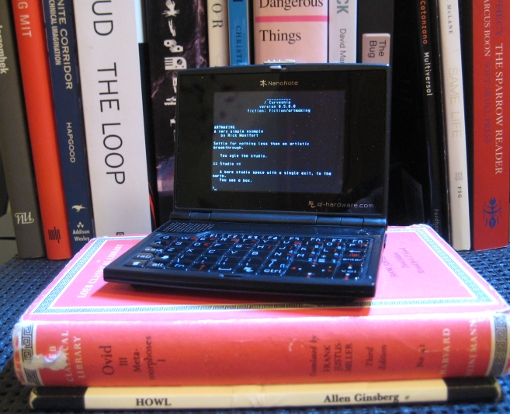

Curveship is a Python framework which will run on any computer that runs Python; I intend to release it under a free software license when it the core aspects of it are complete, well-tested, and well-documented. Rather than repeat what is already online about the system, I’ll just mention here that information about Curveship is available in several papers and in my 2007 dissertation. The best place to begin reading about the system is [my blog, _Post Position_](http://nickm.com/post/tag/curveship/), where papers and my dissertation are linked. My blog posts use the same (simplified) terminology as does the code; these terms (such as “spin” to refer to the specification for narrating) are the current, official ones. Some of my earlier publications, although they represent many aspects of Curveship well, use out-of-date terms.

#### _The Marble Index_

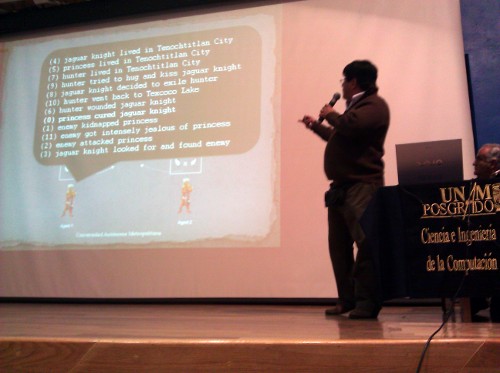

_The Marble Index_ simulates the experiences of a woman who, strangely disjointed in time and reality, finds herself visiting ordinary moments in the late twentieth century; the narration accentuates this character’s disorientation and contributes to the literary effect of incidents. So far, only a few sketches of parts of _The Marble Index_ have been done. In _The Marble Index_, the narrative style is controlled by the interactive fiction program. I am not very far along on this project, but I mention it because I anticipate that, just as the interactive fiction programs takes care of simulating the world in current IF, the program will usually take care of modifying the narrative style in a less direct way. _The Marble Index_ will probably be more representative of how the narrating will be controlled in a “typical” Curveship piece.

#### _Adventure in Style_

_Adventure in Style_ is in part a port of the first interactive fiction, the 1976 _Adventure_ by Will Crowther and Don Woods – one which adds parametric variations in style that are inspired by Raymond Queneau’s _Exercises in Style_ (_Exercises de style_, 1947). For several years, I have been beginning my presentations about Curveship by showing that the goal of the project is to combine _Adventure_ and _Exercises in Style_, because the two pieces show what is essential and compelling about interactive fiction (simulating a storyworld with a text interface) and about narrative variation. Now, in working on a creative project which is supposed to be effective as a stand-alone piece, not only as a demo, I am trying to combine these two much more literally.

In _Adventure in Style_, the player can rather directly control the narrative style by commanding the player character to manipulate an in-game object. The critical object here is the lamp, which the adventurer almost always needs to be holding in the cave. A special case, in which the player chooses to use the standard style throughout an entire traversal, gives the player an experience much like that of running the original _Adventure_ program. The fictional work of _Adventure in Style_ is almost complete, with the cave laid out as in _Adventure_ and many of the treasures and other objects implemented. Although the fiction file has not been fully tested, the map of and most of the puzzles in _Adventure_ are in place. Several of the possible variations in style, but not all the ones that are planned, have been implemented as well.

Several of my interests flow together, and then underground, in _Adventure in Style_. It is a port, and during my investigation of the Atari VCS (Atari 2600) with Ian Bogost as we worked on _Racing the Beam_, I found that ports are fascinating because they involve thinking about the essential aspects of a game and how they can be expressed in different ways across different platforms. When played in the standard narrative mode, one can see that _Adventure in Style_, in reimplementing a previous game, aspires to the unoriginality of Kenneth Goldsmith’s practice of uncreative writing, in which a writer simply transcribes or retypes text, such as a year’s worth of radio weather reports or a particular issue of _The New York Times_. Since narrative variation, the only aspect of the project that doesn’t come from _Adventure_, comes from _Exercises in Style_, _Adventure in Style_ is thoroughly uncreative: neither the original game nor the concept of variation sprang from my fictive forehead. Nevertheless, or perhaps because I have avoided trying to make any real contribution of my own, I find that these two great tastes taste great together. They serve as a way to understand the computer’s power to control the telling of a story and to model an underlying story world.

#### Grue Street

I took _Adventure in Style_ to the first meeting of Grue Street, an interactive fiction writers’ group that I started in Cambridge, Massachusetts as an offshoot of the local IF organization, The People’s Republic of Interactive Fiction. (In the tradition of Infocom’s _The New Zork Times_, we named the group to riff on a local writing center, “Grub Street.” Hopefully this organization won’t follow the lead of the Grey Lady and threaten us with a lawsuit.) Grue Street got off to a good start with six games and seven authors – one game was a collaboration. We required each attendee to bring something playable to the meeting, a “situation” of some sort:

> “Situation” can mean something like a puzzle, task, or conversation, which may take place in one room (or scene) or in several. The term is meant to be pretty open; it’s mainly to encourage authors to have more than just an empty setting (with nothing to do in it) or a lone character or collection of objects (with no reason to interact). You don’t need to have your whole game completed or even sketched out to participate.

The writers interacted with each piece as a group. On the one hand, this left each of us with only one transcript of play to study, but, on the other, it gave authors the opportunity to hear players thinking out loud and talking with each other.

I didn’t come away from the meeting with any ideas for major revisions to _Adventure in Style_, but the group’s reaction did help me think about frame the game, creating a useful welcome message, and choosing a good variation to introduce initially. It also made me realize that it will be hard for some people to see the project as anything more than a demo of Curveship.

#### Three Goals

My work on Curveship has been directed toward three major goals:

1. To advance and support research in natural language generation, narratology, computational creativity, and related fields.

2. To create a functional IF development system that allows authors to create games for players.

3. To enable new, compelling literary and aesthetic experiences.

“Shimmer,” advertised during the first season of _Saturday Night Live_, was a substance designed to be both a floor wax and a dessert topping. To update this for the 21st century, we might image a substance that is a floor wax, a dessert topping, and a hand sanitizer. While the three goals of Curveship do work together in certain ways, in other ways they make the research, development, and creative project seem a bit like “Shimmer Plus.”

An IF development system needs a reliable way for players to download games and probably for them to play games online, and, among other things, it needs a start-of-the-art parser. These are useful for goal 3 but unnecessary for goal 1. Generally, goal 1 and goal 3 involve pushing the envelope in some ways that are similar and some ways that are different, while goal 2 requires stability, documentation, and ease of use.

There are projects that have taken on two major and distinct goals at once. _Façade_ by Michael Mateas and Andrew Stern was an attempt to create a highly distributable, playable, and enjoyable experience that also advanced the state of the art of interactive drama. It was not itself a platform or development system, however. Graham Nelson’s co-development of Inform and _Curses_ involved creating a literary work and the now-dominant IF development system, but Inform (which has since been developed in very intriguing new directions) was not initially focused on expanding the possibilities of IF. Daniel Howe’s RiTa and Ben Fry and Casey Reas’s Processing have been developed first and foremost as general platforms, but have contributed along other lines. Nevertheless, projects that strive toward all three of these goals are rare.

I will be re-opening activity on Curveship this summer and would be glad to hear from people interested in using the system, as this will help me focus my efforts and create a release that works for the community interested in the system’s capabilities.