Developers of digital storytelling systems, take note: The call for papers for the Fifth International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling is now out. Conference to be held November 12-15, 2012 in Spain.

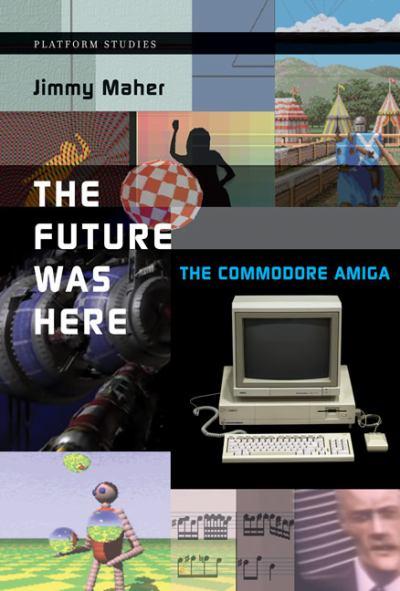

The Amiga Book: Maher’s The Future Was Here

Congratulations to Jimmy Maher on his just-published book, The Future Was Here: The Commodore Amiga. As you might expect, Amazon has a page on it; so does Powell’s Books, for instance.

This MIT Press title is the third book in the Platform Studies series. Jimmy Maher has done an excellent job of detailing the nuts and bolts of the first multimedia computer that was available to consumers, and connecting the lowest levels of this platform’s function to cultural questions, types of software produced, and the place of this system in history. The book considers gaming uses (which many used to brand the Amiga as nothing but a toy) but also media production applications and even, in one chapter, the famous Boing Ball demo.

The Platform Studies series (which also has a page at The MIT Press) is edited by Ian Bogost and yours truly, Nick Montfort, and now has three titles, one about an early videogame console, one about a console still in the current generation and on the market, and this latest title about an influential home computer, the Amiga. We have a collaboration between two digital media scholars and practitioners of computational media; a collaboration between an English professor and a computer science professor; and this latest very well-researched and well-written contribution from an independent scholar who has, for a while, been avidly blogging about many aspects of the history of gaming and creative computing.

Jimmy Maher, not content with his book-writing and voracious, loquacious blogging, has created a website for The Future is Here which is worth checking out. If you were an Amiga owner or are otherwise an Amiga fan, there’s no need to say that you should run, not walk, to obtain and read this book. But it will be of broader interest to all of those concerned with the multimedia capabilities of the computer. Really, even if you had an Atari ST – do give it a read, as it explains a great deal about the relationship between computer technology and creativity, exploring issues relevant to the mid-to-late 1980s and also on up through today.

Star Wars, Raw? Rats!

Un file de Machine Libertine:

Star Wars, Raw? Rats!

… is a videopoem by Natali Fedorova and Taras Mashtalir. The text is a palindrome by Nick Montfort that briefly retells “Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope,” making Han Solo central. The soundtrack is a remix of Commodore 64 music by Sven Schlünzen & Jörg Rosenstiel made by Mashtalir.

The palindrome is a revised version of the one Montfort wrote in 75 minutes for the First World Palindrome Championship, held in Brooklyn on March 16, 2012:

Wow, sagas!

Solo’s deed, civic deed.

Eye dewed, a doom-mood.

A pop …

Sis sees redder rotator.

Radar eye sees racecar X.

Dad did rotor gig.

Level sees reviver!

Solo’s deified!

Solo’s reviver sees level …

Gig rotor did dad!

X, racecar, sees eye.

Radar rotator, redder, sees sis …

Pop a doom-mood!

A dewed eye.

Deed, civic deed.

Solo’s sagas: wow.

Machine Libertine: http://machinelibertine.wordpress.com/

The big-screen premiere of Star Wars, Raw? Rats! will be at MIT in room 32-155 on Monday, April 30, 2012. The screening, which includes a set of films made by members of the MIT community, will begin at 6pm.

Borsuk, Bök, Montfort – May 5, 7pm, Lorem Ipsum

I’m reading soon with our Canadian guest Christian Bök and with my MIT colleague Amaranth Borsuk, who will present _Between Page and Screen_ (published by Siglio Press this year). The gig is at:

Lorem Ipsum Books

1299 Cambridge Street

Inman Square

Cambridge, MA

Ph: 617-497-7669

May 7, 2012 at 7pm

Amaranth Borsuk is the author of _Handiwork_ (2012), the chapbook _Tonal Saw_ (2010), and a collaborative work _Excess Exhibit_ to be released as both a limited-edition book and iPad application in 2012. Her poems, essays, and translations have been published widely in journals such as the _New American Writing, Los Angeles Review, Denver Quarterly, FIELD, and Columbia Poetry Review._ She has a Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing from USC and is currently a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Comparative Media Studies, Writing and Humanistic Studies at MIT where she works on and teaches digital poetry, visual poetry, and creative writing workshops.

Christian Bök is the author of _Crystallography_ (2003), a pataphysical encyclopedia, and of _Eunoia_ (2009), a bestselling work of experimental literature. Bök has created artificial languages for two television shows: Gene Roddenberry’s _Earth: Final Conflict_ and Peter Benchley’s _Amazon._ Bök has also earned accolades for his virtuoso performances of sound poetry (particularly _Die Ursonate_ by Kurt Schwitters). Currently, he is conducting a conceptual experiment called _The Xenotext_ (which involves genetically engineering a bacterium so that it might become not only an archive for storing a poem in its genome for eternity, but also a machine for writing a poem as a protein in response). He teaches English at the University of Calgary.

Nick Montfort writes computational and constrained poetry, develops computer games, and is a critic, theorist, and scholar of computational art and media. He teaches at MIT and is currently serving as president of the Electronic Literature Organization. His digital media writing projects include the interactive fiction system Curveship; the group blog _Grand Text Auto;_ _Ream,_ a 500-page poem written on one day; _2002: A Palindrome Story,_ the longest literary palindrome (according the Oulipo), written with William Gillespie; _Implementation,_ a novel on stickers written with Scott Rettberg; and several works of interactive fiction: _Winchester’s Nightmare, Ad Verbum,_ and _Book and Volume._ His latest book, _Riddle & Bind_ (2010), contains literary riddles and constrained poems.

Straight into the Horse’s Mouth

My word-palindrome writing project (being undertaken as @nickmofo) has been boosted by Christian proselytizing, by Bök’s page. I am delighted to be featured in Christian Bök’s post on Harriet as an instance of conceptual writing on Twitter – named, in fact, right after @Horse_ebooks.

This makes it particularly apt that Christian describes my writing as potential poetic “fodder.” Why not treat this feed of texts as the gift horse that keeps on giving? Please, feel free to make the tweets of @nickmofo into your chew toy.

Steve McCaffery Reading Carnival at Purple Blurb

Steve McCaffery read at MIT in the Purple Blurb series on March 19, 2012. A recording of part of that reading (his reading of Carnival) is embedded above; the text of my introduction follows.

Thank you all for braving the cold to come out today. Did you know that today is officially the last day of Winter? Ever! Winter is officially over forever!

But I come not to bury Winter, but to praise Steve McCaffery, and to introduce him. Steve McCaffery is professor and Gray Chair at the University of Buffalo in the Poetics Program. He comes to us from there, and before, from Canada, where he did much of his pioneering work in sound and concrete poetry. He is one of those people who is know for his non-digital work but without whom the current situation of electronic literature, of digital writing, could not exist. He is in that category, for instance, with Jorge Luis Borges.

You would have me institutionalized for loggorrhea if I attempted to read Steve McCaffery’s entire bibliography and discography to you.

Know, however, that McCaffery was one of the Four Horsemen, along with bpNichol, Rafael Barreto-Rivera, and Paul Dutton. This groundbreaking group of sound poets, numbering almost as many mouths as there are vowels, released several albumbs: “Live in the West,” and “Bootleg,” and “caNADAda.”

McCaffery’s critical writing can found in “North of Intention: Critical Writings 1973-1986” and “Prior to Meaning: The Protosemantic and Poetics” His two-volume selected poems, “Seven Pages Missing,” was published in Coach House in 2000. It earned him his second Governor General’s Awards nomination; his first was for his 1991 book “Theory of Sediment.” More recently, there’s his “Verse and Worse: Selected Poems 1989-2009,” which he and Darren Wershler edited.

And, I’ll mention two other books, his “The Basho Variations,” published in 2007, which consists of different translations and version of Matsuo Basho’s famous haiku, which could be rendered clunkily as “old pond / frog jump in / water sound.” A digital version of this haiku can be seen in Neil Hennesy’s “Basho’s Frogger,” a modified version of the game Frogger in which the first row of floating items is missing so that one can only … you know … jump in. McCaffery is pond and frog and sound, placid and salient and resonant, and we are very lucky to have him here with us tonight.

Finally, I want to mention his extraordinary poem “Carnival.” I’ve taught the first panel to dozens of students here at MIT, so it’s black and red and read all over. The two panels of “Carnival” are incredible documents. If only fragments of them survive in three thousand years, that will be adequate for archaeologists to reconstruct the functioning and history of the typewriter completely. Of course, there’s more to “Carnival” than that material writing technology. But instead of saying more, I should simply let our guest give voice to “Carnival” and other works of his. Please join me in welcoming Steve McCaffery…

On Reading

I was asked to discuss reading (and reading education) from my perspective recently. Here’s the reply I gave…

The students I teach now, like other university students I have taught, have the ability to read. They are perfectly able to move their eyes over a page, or a screen, and recognize the typographical symbols as letters that make up words that make up sentences or lines.

The problems they face usually relate to a narrow concept of reading, which includes an unwillingness to read a wider variety of texts. These are not problems that are restricted to well-qualified, well-educated university students who are expert readers. As the networked computer provides tremendous access to writing and transforms our experience of language, all of are asked to rethink and enlarge our reading ability.

One problem with reading too narrowly is the view that reading is only instrumental. People who spend a significant portion of their lives speaking to their friends and family members about nothing – simply because they enjoy company and conversation – will sometimes refuse to believe that reading can a pleasure in and of itself. Reading is too often seen only as a tool, to allow one to follow instructions, determine the ingredients in packaged food, or to learn about some news event or underlying argument.

To try to enlarge a student’s idea of reading, I might present a text that, whether said aloud or imagined to one’s self, communicates almost nothing and is simply beautiful. To take a very conservative example:

Glooms of the live-oaks, beautiful-braided and woven

With intricate shades of the vines that myriad-cloven

Clamber the forks of the multiform boughs,—

Emerald twilights,—

Virginal shy lights,

Wrought of the leaves to allure to the whisper of vows,

When lovers pace timidly down through the green colonnades

Of the dim sweet woods, of the dear dark woods,

Of the heavenly woods and glades,

That run to the radiant marginal sand-beach within

The wide sea-marshes of Glynn;—

This is from an American poem, Sidney Lanier’s The Marshes of Glynn, published in 1878. It shows that it is not necessary to turn to some almost unrecognizable avant-garde poem to see how sound can overflow meaning, providing a pleasure that has almost nothing to do with communication. Lanier had a very musical view of poetry, but this poem does not need to be sung or played by an expert musician. Anyone who can read English can bring it alive.

Another problem with a narrow concept of reading is not understanding the full range of what can be read. Students are comfortable reading pages and feeds, and reading emails and IMs, but it is not always as clear how they might read around in the library to explore as researchers, how they might read an unusual Web site or other complex digital object, or how they might read their daily urban environment. Those of us familiar with art and literature will habitually “view” something in the former category, perhaps not even noticing that it may be legible.

To address this issue, I do turn to an almost unrecognizable avant-garde poem, Steve McCaffery’s Carnival, the first panel. This Canadian concrete poem, typed in a red and black in an amazing configuration of characters, seems to many to be an artwork but was created by a poet and published as poetry. Unlike the most famous Brazilian concrete poems, this is an example of “dirty concrete” that many do not even see, initially, as legible. Students who are able to assume the attitude of readers find that it can be read, however, and that it has an amazing ability to disclose things about reading: Our assumptions in how to trace words and letters in space, our ability to fill in partly-missing and entirely missing letters, the question of how to sound fragments of words and patterns of punctuation marks.

The first page of Carnival, panel one, is from the

Coach House online edition.

When people learn how to speak a language – whether as an infant or later in life – they sometimes simply babble or chat. Everyone would agree that a learner should be allowed to enjoy speaking and listening, to enjoy making and hearing the sounds of a language, in addition to caring about the purposeful uses of that language. I believe it’s the same for reading. Reading is more than just a process of decipherment that provides an information payload. It gives us special access to the pleasures of language and to its complexities. Any sighted person, with or without any English, can look at the first panel of Carnival. But only a reader can both view it and read it, comprehending it as a visual design and as language. If a reader is unwilling to hear The Marshes of Glynn, it could be understood simply as a botanical catalog with some lovers traipsing about here and there. To hear, instead, the play of sound and sense, is to encounter something new, to understand another aspect of words and how they work.

Interactive Fiction Hits the Fan

Although a recent IF tribute to a They Might Be Giants album might help to delude some people about this, interactive fiction these days is not about fandom and is unusually not made in reference to and transformation of previous popular works.

An intriguing exception, however, can be found in the just-released Muggle Studies, a game by Flourish Klink that takes place in the wonderful wizarding world of Harry Potter. The player character is of the non-magical persuasion, but gets to wander, wand-free, at Hogwarts, solve puzzles, and discover things that bear on her relationship with her ex-girlfriend. You can play and download the game at the Muggle Studies site.

Apollo 18+20, a Tribute to an Album in Interactive Fiction

The organizer of the People’s Republic of Interactive Fiction, Kevin Jackson-Mead, has organized and co-written a tribute to the 1992 They Might Be Giants Album, Apollo 18. At the PR-IF site, you can play and download 38 short games corresponding to every song (including the “Fingertips” songs) on the album. With its retro cachet, it may be today’s version of Dial-a-Song:

Big Reality

I went last weekend to visit the Big Reality exhibit at 319 Scholes in Bushwick, Brooklyn. It was an adventure and an excellent alternative to staying around in the East Village on March 17, the national day of drunkenness. The gallery space, set amid warehouses and with its somewhat alluring, somewhat foreboding basement area (I had to bring my own light source to the bathroom), was extremely appropriate for this show about tabletop and computer RPGs and their connections to “real life.” Kudos to Brian Droitcour for curating this unusual and incisive exhibit.

A few papers of mine are probably the least spectacular contribution to the show. There are three maps of interactive fiction games that I played in the 1980s and my first map of nTopia, drawn as I developed Book and Volume. The other work includes some excellent video and audio documentation of WoW actions and incidents; fascinatingly geeky video pieces; the RPGs Power Kill, Pupperland, and Steal Away Jordan; player-generated maps; a sort of CYOA in which you can choose to be a butcher for the mob or Richard Serra; and an assortment of work in other media. Plus, the performance piece “Lawful Evil,” in which people play a tabletop RPG in the center of the gallery, is running the whole time the show is open.

Which, by the way, is until March 29.

And, the catalog is excellent, too, with essays and other materials that bear on the question of how supposedly escapist role-playing tunnels into reality.

Palindrome “Sagas”

Marty Markowitz, borough president of Brooklyn, said his borough was “the heart of America” in welcoming the 35th Annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament. My heart was certainly in Brooklyn last weekend, both literally and figuratively. I was there to participate in the First Annual World Palindrome Championship on Friday and, on Saturday, to visit Big Reality, a wonderful, scruffy art show that included some of my work. More on Big Reality soon; here’s a belated note about the WPC.

I made into New York in time to meet at Jon Agee’s sister’s house in Brooklyn with him and several other palindromists who would be competing that evening. (Agee is a cartoonist whose books include Go Hang a Salami! I’m a Lasagna Hog! and Palindromania!) The other competitors included a fellow academic, John Connett, who is professor of Biostatistics at the University of Minnesota and an extremely prolific producer of sentence-length palindromes. Martin Clear, another author of many, many sentence-length palindromes, came from Australia. Barry Duncan, a Somerville resident and thus practically my neighbor, also joined us. Another competitor was Mark Saltveit, editor of The Palindromist and a stand-up comedian. And Douglas Fink, who won a celebrity palindrome contest with his now-famous entry “Lisa Bonet ate no basil,” was the audience contestant selected to join us.

I met Barry and Doug later that day, and had a great time sitting around and discussing palindromes with the others over lunch. We had plenty to talk about. It was interesting to see that we also had different perspectives, interests, and terms associated with the art. Jon thought “Er, eh – where?” was a good palindrome, probably in part because he was imagining how to illustrate it or frame it in a cartoon in a funny way. The others generally thought this one was bogus. A sentence was the desired outcome for most of us, while I was a fan (and writer) of longer palindromes. And, as we found out that night, the audience had their own tropisms and aesthetics when it comes to palindromes.

We had 75 minutes to write up to three palindromes that we’d read to the crowd, which was to vote for their two favorite. There were three possible constraints given: Use X and Z; Refer to events in the news in the past year; or refer to the crossword tournament itself. Here’s what I came up with, using the first constraint:

The Millennium Falcon Rescue

by Nick Montfort

Wow, sagas … Solo’s deed, civic deed.

Eye dewed, a doom-mood.

A pop.

Sis sees redder rotator.

Radar sees racecar X.

Oho! Ore-zero level sees reviver!

Solo’s deified!

Solo’s reviver sees level: ore-zero.

Oho: X, racecar, sees radar.

Rotator, redder, sees sis.

Pop a doom-mood!

A dewed eye.

Deed, civic deed.

Solo’s sagas: wow.

All of the results (and the text of the palindromes) are up on The Palindromist site – take a look!

Mark Saltveit became champ with a short palindrome about acrobatic Yak sex. John Connett got 2nd, Jon Agee 3rd, and yours truly 4th.

Which is the longest?

In mine, I count 54 words, 237 letters, and 327 characters. If “doom-mood” and the like are single words, we’d have 50 words. Mark says on The Palindromist site that it’s 57 words long; I’m not sure how the counting was done there.

In Barry’s, the only other possible contender, I count 70 words (as does Mark), 184 letters, and 311 characters. Some of those words are “7” and have no letters in them, as you’ll note if you check out the results page.

So, they’re both the longest: Barry’s has the most words, while mine has the most letters and characters.

It’s a sort of odd comparison, because the constraint I used (employ only palindromic words, counting things like “ore-zero” as words) let me reframe the problem as that of constructing a word palindrome with a restricted vocabulary. Of course, you should be very very impressed anyway, with my general cleverness and so on, but I think Barry chose a more difficult feat at the level of letter-by-letter construction.

Does length matter?

Yes. A palindrome should be the right length. 2002 words is a good length if you’re trying to write a palindromic postmodern novel. For a snappy statement, a short sentence is a good length. I think some of the best palindromes are longer than a sentence and much shorter than 2002. My last edits to “The Millennium Falcon Rescue” were to cut several words (an even number, of course), and maybe I should have cut more? And, should I revise this one, I might cut the word that was included for the sake of the Z.

What about those palindromists?

The most interesting thing about this event, for me, was a gathering focused on palindrome-writing. Kids know what palindromes are, the form of writing has been around for more than a thousand years, many people have palindromes memorized, and there are a handful of famous books … but as I see it there hasn’t even been a community of palindrome-writers, discussing writing methods, coming up with common terms and concepts, sharing poetic and aesthetic ideas.

Well, perhaps there has been, in the Bletchley Park codebreakers. But I only learned about them because I met Mark, who is one of the people researching the origins of famous palindromes. And that was, due to wartime security, a very secretive group.

It was great having the Championship hosted by Will Shortz at the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, with many puzzle-solver and -constructors who are interested in formal engagements with language. Of course, palindrome events would fit will at other sorts of gatherings that are focused on poetry and writing, too.

Whether or not we have another championship (which would be great), it would be nice to have another summit of some sort and to build a community of practice around this longstanding practice. Particularly if we can get someone named Tim to join us: Tim must summit!

What If

was making a movie starring

Robert “can’t stop sparkling” Pattinson

based on a novel by

Don “say the word” DeLillo

…

Cosmopolis

…

about a fantastically wealthy guy trying to cross Manhattan in his limo to get a haircut

…

(Thanks to Mark Sample for alerting me to the trailer.)

An Image Is Worth a Thousand Midi-Chlorians

Digging beyond Data

Noah Wardrip-Fruin, a friend and collaborator, has a great editorial in Inside Higher Ed today. It’s called “The Prison-House of Data” and addresses a prevalent (if not all-inclusive) view of the digital humanities that focuses on the analysis of data and that overlooks how we can understand computation, too.

The Purpling

I was recently notified that “The Purpling” was no longer online at its original published location, on a host named “research-intermedia.art.uiowa.edu” which held The Iowa Review Web site. In fact, it seems that The Iowa Review Web is missing entirely from that host.

My first reaction was put my 2008 hypertext poem online now on my site, nickm.com, at:

http://nickm.com/poems/the_purpling/

Fortunately, TIWR has not vanished from the Web. I found that things are still in place at:

http://iowareview.uiowa.edu/TIRW/

And “The Purpling” is also up there. Maybe I was using a non-canonical link to begin with? Or maybe things moved around?

CS and CCS

Here’s a post from a computer scientist (Paul Fishwick) that not only embraces critical code studies (CCS), it suggests that collaborations are possible that would be a “remarkable intersection of culture and disciplines” – where the object of study and the methods are shared between the humanities and computer science. Radical.

1st Annual World Palindrome Championship

It’s this Friday in Brooklyn, and I’ll be one of six competitors.

This Friday night I’ll be competing in the First Annual World Palindrome Championship. If you insist, you can call it the First or the Inaugural World Palindrome Championship, but that’s the name of the event.

Er, Eh – Where?

The event will take place in Brooklyn at the New York Marriott at the Brooklyn Bridge. The competition, with a 75-minute time for palindrome composition based on a prompt, will kick off the 35th Annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament and will start at 8pm. (Those cruciverbalists like to stay up late.) It’s all run by Will Shortz, crossword puzzle editor for The New York Times. The championship is the first thing on the tournament schedule.

Name no one man!

Actually, one man is almost sure to be named. The five competitors already selected are Jon Agee, Martin Clear, John Connett, humble narrator Nick Montfort, and Mark Saltveit. Jon Agee has authored books of cartoons illustrating palindromes, including Palindromania! Martin Clear penned “Trade life defiled art” and is making a trip from Australia for the event. John Connett is a fellow academic whose wonderful palindromic quips include “Epic Erma has a ham recipe.” Mark Saltveit is a stand-up comedian and found and editor of The Palindromist, the only magazine specific to this form that I know. And I suppose I got into this by writing the 2002-word palindrome 2002: A Palindrome Story with William Gillespie. The whole list, with pictures and further links, is up on Saltveit’s page for the event.

A competitor will be selected from the audience on Friday based on a palindrome written and submitted that day. If this is a woman or a pair of identical twin collaborators, there is some chance that no one man will be named. Unless one of these miraculously appears and is selected, though, we will unfortunately miss the company of my collaborator William, Mike Maguire (author of Drawn Inward and Other Poems), Demetri Martin, Harry Mathews, and many other top practitioners of the art. For a first gathering of palindrome-writers, though, who can complain?