February 14 is Valentine’s Day for many; this year, it’s also Ash Wednesday for Western Christians, both Orthodox and unorthodox. Universally, it is Harry Mathews’s birthday. Harry, who would have been 94 today, was an amazing experimental writer. He’s known to many as the first American to join the Oulipo.

Given the occasion, I thought I’d write a blog post, which I do very rarely these days, to discuss my poetics — or, because mine is a poetics of concision, my “poetix.” Using that word saves one byte. The term may also suggest an underground poetix, as with comix, and this is great.

Why write poems of any sort?

Personally, I’m an explorer of language, using constraint, form, and computation to make poems that surface aspects of language. As unusual qualities emerge, everything that language is entangled with also rises up: Wars, invasions, colonialism, commerce and other sorts of exchange between language communities, and the development of specialized vocabularies, for instance.

While other poets have very different answers, which very often include personal expression, this is mine. Even if I’m an unusual conceptualist, and more specifically a computationalist, I believe my poetics have aspects that are widely shared by others. I’m still interested in composing poems that give readers pleasure, for instance, and that awaken new thoughts and feelings.

Why write computational poems?

Computation, along with language, is an essential medium of my art. Just as painters work with paint, I work with computation.

This allows me to investigate the intersection of computing, language, and poetry, much as composing poems allows me to explore language.

Why write tiny computational poems?

Often, although not always, I write small poems. I’ve even organized my computational poetry page by size.

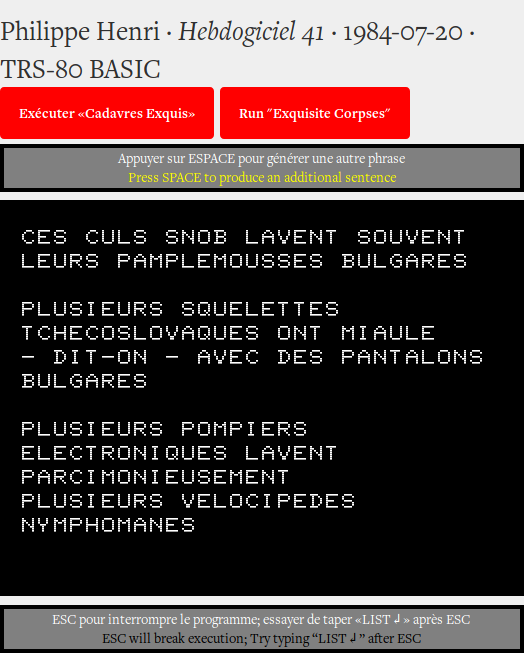

Writing very small-scale computational poems allows me to learn more about computing and its intersection with language and poetry. Not computing in the abstract, but computing as embodied in particular platforms, which are intentionally designed and have platform imaginaries and communities of use and practice surrounding them.

For instance, consider the modern-day Web browser. Browsers can do pretty much anything that computers can. They’re general-purpose computing platforms and can run Unity games, mine Bitcoin, present climate change models, incorporate the effects of Bitcoin mining into climate change models, and so on and so on. But it takes a lot of code for browsers to do complex things. By paring down the code, limiting myself to using only a tiny bit, I’m working to see what is most native for the browser, what this computational platform can most **essentially* accomplish.

Is the browser best suited to let us configure a linked universe of documents? It’s easy to hook pages together, yes, although now, social media sites prohibit linking outside their walled gardens. Does it support prose better than anything else, even as flashy images and videos assail us? Well, the Web is predisposed to that: One essential HTML element is the paragraph, after all. When boiled down as much as possible, there might be something else that HTML5 and the browser is really equipped to accomplish. What if one of the browser’s most essential capabilities is that of … a poetry machine?

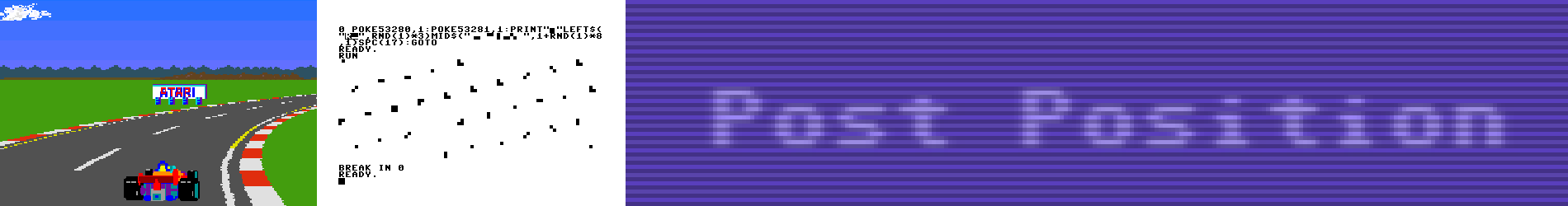

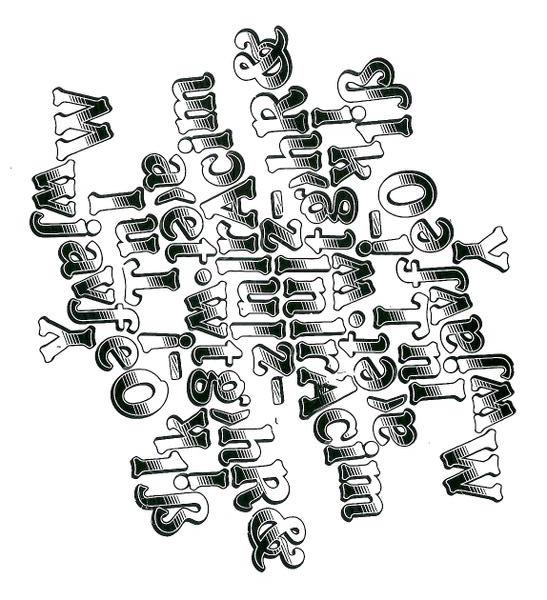

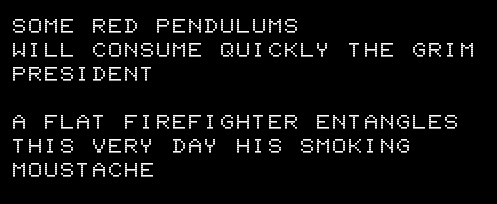

One can ask the same questions of other platforms. I co-authored a book about the Atari VCS (aka Atari 2600), and while one can develop all sorts of things for it (a BASIC interpreter, artgames, demos, etc.), and I think it’s an amazing platform for creative computing, I’m pretty sure it’s not inherently a poetry machine. The Atari VCS doesn’t even have built-in characters, a font in which to display text. On the other hand, the Commodore 64 allows programmers to easily manipulate characters; change the colors of them individually; make them move around the screen; replace the built-in font with one of their own; and mix letters, numbers, and punctuation with an set of other glyphs specific to Commodore. This system can do lots of other things — it’s a great music machine, for instance. But visual poetry, with potentially characters presented on a grid, is also a core capability of the platform, and very tiny programs can enact such poetry.

I’ve written at greater length about this in “A Platform Poetics / Computational Art, Material and Formal Specificities, and 101 BASIC POEMS.” In that article, I focus on a specific, ongoing project that involves the Commodore 64 and Apple II. More generally, these are the reasons I continue to pursue to composition of very small computational poems on several different platforms.