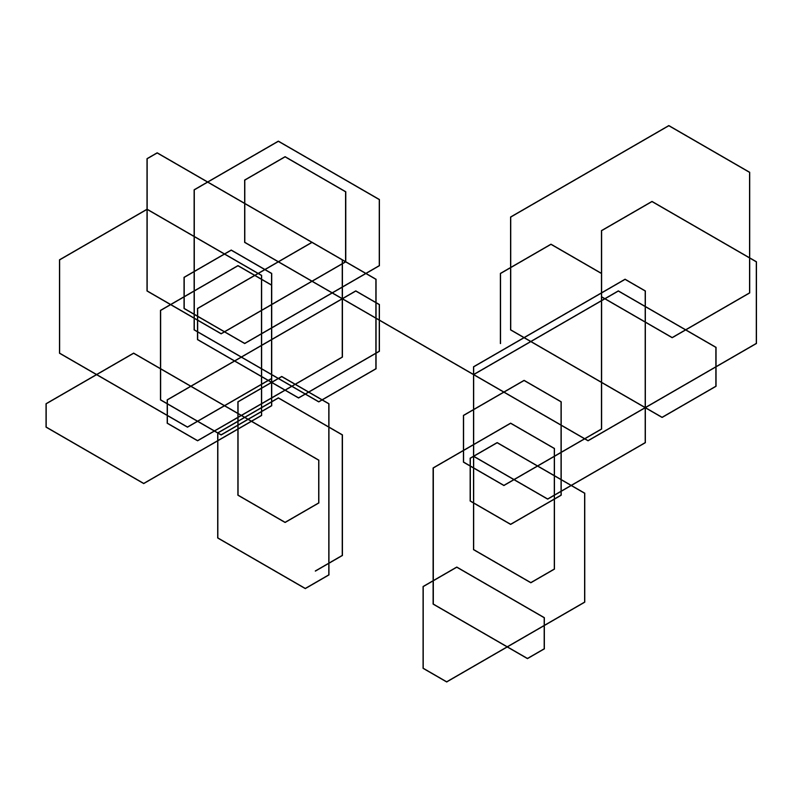

The Library of Babel – Hexagonal Drawing in English

Christian Bök

2020

828px × 828px JPEG

FLY PIECE

Cabaret #7

Panthéon

SOMEONE: Amanda

“Am well. Thinking of you always. Love.”

Outtake

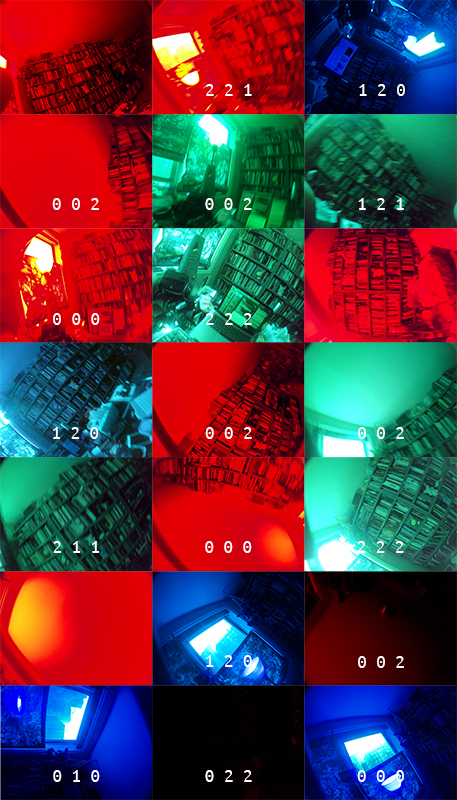

Visual Entanglement, 2020

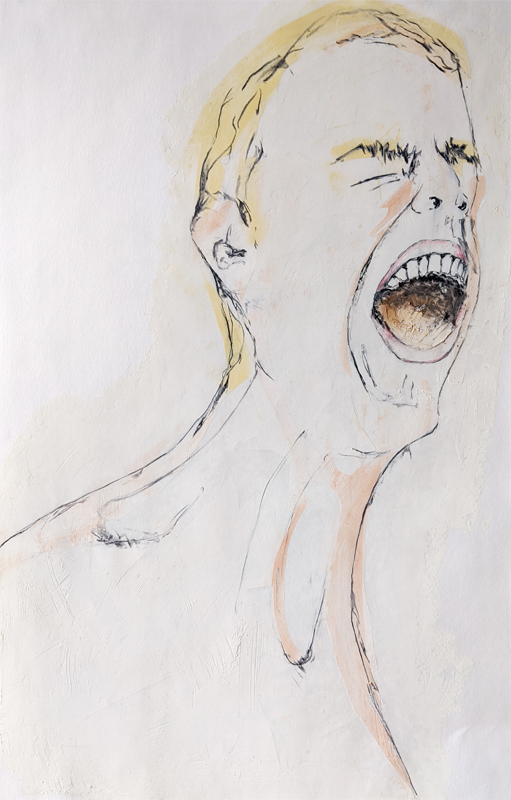

Head 4.054

Yellow Melting Like a Firework Petal

THESE N—-S IS WATCHING

Devil May Care

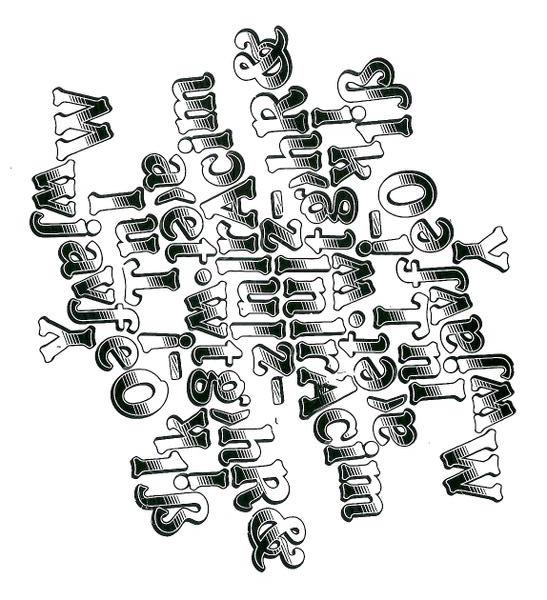

WordHack Book Table

This May 21, 2020 at 7pm Eastern Time is another great WordHack!

A regular event at Babycastles here in New York City, this WordHack will be fully assumed into cyberspace, hosted as usual by Todd Anderson but this time with two featured readings (and open mic/open mouse) viewable on Twitch. Yes, this is the link to the Thursday May 21, 2020 WordHack!

There are pages for this event up on Facebook and withfriends.

I’m especially enthusiastic about this one because the two featured readers will be sharing their new, compelling, and extraordinary books of computer-generated poetry. This page is a virtual “book table” linking to where you can buy these books (published by two nonprofit presses) from their nonprofit distributor.

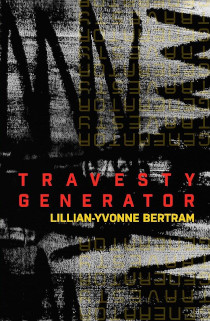

Lillian-Yvonne Bertram will present Travesty Generator, just published by Noemi Press. The publisher’s page for Travesty Generator has more information about how, as Cathy Park Hong describes, “Bertram uses open-source coding to generate haunting inquiring elegies to Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner, and Emmett Till” and how the book represents “taking the baton from Harryette Mullen and the Oulipians and dashing with it to late 21st century black futurity.”

Lillian-Yvonne Bertram will present Travesty Generator, just published by Noemi Press. The publisher’s page for Travesty Generator has more information about how, as Cathy Park Hong describes, “Bertram uses open-source coding to generate haunting inquiring elegies to Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner, and Emmett Till” and how the book represents “taking the baton from Harryette Mullen and the Oulipians and dashing with it to late 21st century black futurity.”

Jörg Piringer will present Data Poetry, just published in his own English translation/recreation by Counterpath. The publisher’s page for Data Poetry offers more on how, as Allison Parrish describes it, Jörg’s book is a “wunderkammer of computational poetics” that “not only showcases his thrilling technical virtuosity, but also demonstrates a canny sensitivity to the material of language: how it looks, sounds, behaves and makes us feel.”

Jörg Piringer will present Data Poetry, just published in his own English translation/recreation by Counterpath. The publisher’s page for Data Poetry offers more on how, as Allison Parrish describes it, Jörg’s book is a “wunderkammer of computational poetics” that “not only showcases his thrilling technical virtuosity, but also demonstrates a canny sensitivity to the material of language: how it looks, sounds, behaves and makes us feel.”

Don’t Venmo me! Buy Travesty Generator from Small Press Distribution ($18) and buy Data Poetry from Small Press Distribution ($25).

SPD is well equipped to send books to individuals, in addition to supplying them to bookstores. Purchasing a book helps SPD, the only nonprofit book distributor in the US. It also gives a larger share to the nonprofit publishers (Noemi Press and Counterpath) than if you were to get these books from, for instance, a megacorporation.

Because IRL independent bookstores are closed during the pandemic, SPD, although still operating, is suffering. You can also support SPD directly by donating.

I also suggest buying other books directly from SPD. Here are several that are likely to interest WordHack participants, blatantly including several of my own. The * indicates an author who has been a featured presenter at WordHack/Babycastles; the books next to those asterisks happen to all be computer-generated, too:

- Articulations, Allison Parrish *

- Mexica: 20 Years-20 Stories [20 años-20 historias], Rafael Pérez y Pérez *

- The Truelist, Nick Montfort *

- Encomials: Sonnets from Pentametron, Ranjit Bhatnagar *

- Machine, Unlearning, Li Zilles *

- A Noise Such as a Man Might Make, Milton Läufer *

- Ringing the Changes, Stephanie Strickland *

- #!, Nick Montfort *

- How to do Privacy in the 21st Century, Peter Burnett

- 2×6, Nick Montfort *, Serge Bouchardon, Andrew Campana, Natalia Fedorova, Carlos León, Aleksandra Mal/ecka, Piotr Marecki

- Hackers, Aase Berg

Thanks for those who want to dig into these books as avid readers, and thanks to everyone able to support nonprofit arts organizations such as Babycastles, Small Press Distribution, Noemi Press, and Counterpath.

Sonnet Corona

“Sonnet Corona” is a computer-generated sonnet, or if you look at it differently, a sonnet cycle or very extensive crown of sonnets. Click here to read some of the generated sonnets.

The sonnets generated are in monometer. That is, each line is of a single foot, and in this case, is of strictly two syllables.

They are linked not by the last line of one becoming the first line of the next, but by being generated from the same underlying code: A very short web page with a simple, embedded JavaScript program.

Because there are three options for each line, there are 314 = 4,782,969 possible sonnets.

I have released this (as always) as free software, so that anyone may share, study, modify, or make use of it in any way they wish. To be as clear as possible, you should feel free to right-click or Command-click on this link to “Sonnet Corona,” choose “Save link as…,” and then edit the file that you download in a text editor, using this file as a starting point for your own project.

This extra-small project has as its most direct antecedent the much more extensive and elaborate Cent mille milliards de poèmes by Raymond Queneau.

My thanks go to Stephanie Strickland, Christian Bök, and Amaranth Borsuk for discussing a draft of this project with me, thoroughly and on short notice.

Against “Epicenter”

New York City, we are continually told, is now the “epicenter” of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Italy is the world’s “epicenter.” This term is used all the time in the news and was recently deployed by our mayor here in NYC.

I’m following up on a February 15 Language Log post by Mark Liberman about why this term is being used in this way. Rather than asking why people are using the term, I’m going to discuss how this word influences our thinking. “Epicenter” leads us to think about the current global pandemic in some unhelpful ways. Although less exciting, simply saying something like “New York City has the worst outbreak” would actually improve our conceptual understanding of this crisis.

“Epicenter” (on the center) literally means the point on the surface of the earth nearest to the focus of a (below-ground) earthquake. It can be used figuratively — Sam did not keep the apartment very tidy; Upon entering the kitchen, we found that it was the epicenter — but there’s only the one literal meaning.

One effect of the term is a sort of morphological pun: There’s a COVID-19 “epi-center” because this is an “epi-demic,” a disease which is “on the people.” But on March 11, the World Health Organization said that COVID-19 is worse than an epidemic, it’s a pandemic. Indeed, it is a global pandemic, spreading everywhere. So what might have been a useful pun back in February is now an understatement.

Beyond that, “epicenter” is metaphorical in the sense of directing us to a particular conceptual metaphor (see George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By, 1980, and Lakoff’s article “The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor,” 1993). This sort of metaphor is not just a rhetorical figure or flourish, not a surface feature of language like the “epi-” pun. It is a fundamental way of understanding a target domain (the pandemic) in terms of a source domain (an earthquake).

To give this complex metaphorical mapping a name, we can call it A HEALTH DISASTER IS A SEISMOLOGICAL DISASTER or more simply A PANDEMIC IS AN EARTHQUAKE. But these are just names; we’d need to explore what is being mapped from our earthquake-schema to our pandemic-schema to really think about what’s going on there.

I will note that this metaphor usefully emphasizes some things about the pandemic: its unexpected onset, the extensive devastation, and the cost to human life. While such mappings are always incomplete, if we try to make a more extensive mapping, we can find ourselves more confused than helped.

Earthquakes are localized to a certain place (unlike a global pandemic) and they occur during a short period of time (unlike a global pandemic). So the metaphor incorrectly suggests that our current disaster is happening once, in one place, and thus we will be able to clean up from this localized, short-term event with appropriate disaster relief.

The most critical aspect of our current crisis is not part of the earthquake metaphor at all. There is no entailment or suggestion from the earthquake metaphor that we are dealing with something that can be transmitted or is communicable. Instead of rallying to an earthquake meeting point, we now need to remain apart from each other to slow the spread of disease.

I’d going to go even deeper in thinking about the “epicenter” concept. Why does a global pandemic (a disease affecting “all the people”) have any sort of center at all?

Metaphor, as it is now understood, is based on ways of thinking that are grounded in bodily experience, including those cognitive structures called image schemas. One of these, detailed by Mark Johnson in The Body in the Mind, 1987 and also discussed by George Lakoff in Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, 1987, is the CENTER-PERIPHERY image schema. It relates to body, and our recognition of the heart, for instance, as being central and one of our toes as being more peripheral. We worry less if we’ve cut a toe than if we’ve cut our heart. Even if lose a toe, we can keep living, which we can’t do without our heart.

So, since this pandemic has one or more CENTERS, does that mean that it’s not so important to worry about the PERIPHERIES of COVID-19? Do we need to be concerned about the center but, if we are somewhere on the margins, is it okay to have parties or get into other situations that may foster transmission of the virus? Is that the way to think about a global pandemic, where outbreaks are occurring everywhere? Obviously, I feel that it’s not best.

The alternative image schemas we can use to develop alternative metaphors are CONTAINMENT and LINER SCALE. “Outbreak” is pretty clearly based on the CONTAINMENT image schema. Some places do have outbreaks that are worse and more serious than other places. Hence, LINEAR SCALE. This would mean saying that, for instance:

Italy has the “worst outbreak of the global pandemic”

NYC has the “worst US outbreak of the global pandemic”

These statements indicate that COVID-19 is a global outbreak that must be CONTAINED, and the implication is that it must be contained everywhere. It isn’t something that hits one place at one time, and doesn’t have a CENTER people can simply flee from in order to be safe. It also admits that the various outbreaks around the world are on a SCALE and can be worse in some places, as of course they are.

I shouldn’t need to explain that I have no expertise or background in public health; What I know, and the information I trust, comes from reading official public health sources (the WHO and CDC). It may seem silly to some (even if you’ve read this far) that I’ve gone off at such length about a single word that’s in the current discourse. I’ve bothered to write this because I’m a poet and have been studying metaphor (in the sense of conceptual metaphor) for many years. I believe the metaphors we live by are very important.

In George Lakoff and Mark Turner’s More Than Cool Reason, 1989, they make the case that metaphor is not what it was assumed to be in poetry discussions for many centuries. It is completely different, certainly not restricted to literature, and indeed is central to everyday thinking. However, in their view, the role of poets is extremely important: “Poets are artists of the mind.” They argue that we (poets) can help to influence our culture and open up more productive and powerful ways of thinking about matters of crucial importance, via developing and inflecting metaphors. I believe this, and hope that other poets will, too.

Sea and Spar Between 1.0.2

When it rains, it pours, which matters even on the sea.

Thanks to bug reports by Barry Rountree and Jan Grant, via the 2020 Critical Code Studies Working Group (CCSWG), there is now another new version of Sea and Spar Between which includes additional bug fixes affecting the interface as well as the generation of language.

As before, all the files in this version 1.0.2.are available in a zipfile, for those who care to study or modify them.

Sea and Spar Between 1.0.1

Stephanie Strickland and I published the first version of Sea and Spar Between in 2010, in Dear Navigator, a journal no longer online. In 2013 The Winter Anthology republished it. That year we also provided another version of this poetry system for Digital Humanities Quarterly (DHQ), cut to fit the toolspun course, identical in terms of how it functions but including, in comments within the code, what is essentially a paper about the detailed workings of the system. In those comments, we wrote:

The following syllables, which were commonly used as words by either Melville or Dickinson, are combined by the generator into compound words.

However, due to a programming error, that was not the case. In what we will now have to call Sea and Spar Between 1, the line:

syllable.concat(melvilleSyllable);

does not accomplish the purpose of adding the Melville one-syllable words to the variable syllable. It should have been:

syllable = syllable.concat(melvilleSyllable);

I noticed this omission only years later. As a result, the compound or kenning “toolspun” never was actually produced in any existing version of Sea and Spar Between, including the one available here on nickm.com. This was a frustrating situation, but after Stephanie and I discussed it briefly, we decided that we would wait to consider an updated version until this defect was discovered by someone else, such as a critic or translator.

It took a while, but a close reading of Sea and Spar Between by Aaron Pinnix, who considered the system’s output rather than its code, has finally brought this to the surface. Pinnix is writing a critique of several ocean-based works in his Fordham dissertation. We express our gratitude to him.

The result of adding 11 characters to the code (obviously a minor sort of bug fix, from that perspective) makes a significant difference (to us, at least!) in the workings of the system and the text that is produced. It restores our intention to bring Dickinson’s and Melville’s language together in this aspect of text generation. We ask that everyone reading Sea and Spar Between use the current version.

Updated 2020-02-02: Version 1.0.2 is now out, as explained in this post.

We do not have the ability to change the system as it is published in The Winter Anthology or DHQ, so we are presenting Sea and Spar Between 1.0.1 1.0.2 here on nickm.com. The JavaScript and the “How to Read” page indicate that this version, which replaces the previous one, is 1.0.1 1.0.2.

Updated 2020-02-02: Version 1.0.2 is the current one now and the one which we endorse. If you wish to study or modify the code in Sea and Spar Between and would like the convenience of downloading a zipfile, please use this version 1.0.2.

Previous versions, not endorsed by us: Version 1 zipfile, and version 1.0.1 zipfile. These would be only of very specialized interest!

Incidentally, there was another mistake in the code that we discovered after the 2010 publication and before we finished the highly commented DHQ version. We decided not to alter this part of the program, as we still approved of the way the system functioned. Those interested are invited to read the comments beginning “While the previous function does produce such lines” in cut to fit the toolspun course.