_I delivered this as the opening keynote at DiGRA Nordic 2012, today, June 7._

#### 1. The World of the Scene

Welcome to the world of the scene, to the summer of 2012, to that Earth where the demoscene is pervasive. Computers are mainly part of our culture because of their brilliant ability to produce spectacles, computationally generated spectacles that are accompanied by music, all of which is produced from tiny pieces of code, mostly in assembly language, always in real time. The coin of the realm is the demoscene _production,_ which includes graphics and chiptunes but is principally represented by demos and their smaller cousins, intros. The coin of the realm – although these are not exchanged commercially, but freely shared with all lovers of computation and art, worldwide.

The ability of these programs to connect the affordances of the computer with people’s capabilities for aesthetic appreciation, and the ability of programmers to continually uncover more potential in machines of whatever vintage, is the leading light in our world’s cultural activity and in the development of new technology as well. And it burns so brightly.

Computers, originally imagined as instruments of war, as business machines, as scientific apparatus, now are seen as platforms for beauty, as systems that can be rhythmical and narrative and can present architectural and urban possibilities as well as landscapes. One plays with the computer not by picking up a controller that is ready to receive one’s twitches but by thinking and typing at great length, by loading and storing, by writing programs.

People congregate in immense gatherings to program together and to appreciate intros, demos, and other productions running on the appropriate hardware. Of course they attend the classic parties such as Assembly in Helsinki, where they fill the Hartwall Areena. They come as well to the edgy and artsy Alternative Party in Finland. They also travel every summer to this world’s largest American demoparty, Segfault, which takes place at the Los Angeles Convention Center. Few of the sceners are even aware that a small but dedicated group of gamers is meeting at the same time in the same city, in a hotel, for their so-called “E3” gathering.

To exchange creative computer programs with one another, to annotate them and discuss them, a number of widely-used social media platforms have sprung up in our scener world. Some people used the video sharing service YouTube, but it is far less popular than YouCode, which allows the full power of the computer to be tapped and facilitates the exchange of assembly language programs.

In our scener world, a vibrant group of game developers and game players remains, of course, although they are not much talked about in the popular press, in the art world, or in academic discourse. California is something of a backwater in this relatively small pond of game development. Some development of games is still done there – first-person shooters, moderately multiplayer online role-playing games, and so on – but the games that have gained some purchase with the public come from elsewhere.

The two most prominent game developers are from Japan and Wales: Tetsuya Mizuguchi and Jeff Minter. Mizuguchi’s _Rez,_ as with with his many other excellent games, connects music and actions in a way that mainstream computer users – sceners – find particularly compelling. Minter’s graphical prowess, seen in _GridRunner_ and many other games, appeals to the popular crowd of sceners, too, as does his whimsical inclusion of ungulates in his games. The games by these two consistently have earned the highest level of praise from the world at large: “that could almost be a production.”

#### 2. Scener vs. Gamer

Now, as enjoyable as this vision is, let’s put this scener world on hold for a moment – not, of course, by pressing select on our XBox 360 controller, but by pressing the freeze button on our Commodore 64’s The Final Cartridge III – or, if we must resort to emulation, by selecting File > Pause from the VICE menus.

How does the scener world that can be glimpsed in the real Summer Assembly in Helsinki relate to this other universe we have surely heard about, the gamer world of Winter Assembly and this summer’s DiGRA Nordic in Tampere? How do the origins of computer and videogaming relate to the origins of the scene?

To relate gaming and the scene, something of course must be said about the nature of the demoscene. I am not here to provide a history of the scene, which is, of course, almost entirely a Northern European phenomenon and which is particularly strong in Finland. It would be absurd for me to come here and pretend to be an authority on the scene, ready to tell you the special things that I know and that you should know about it. It would be as absurd as my coming to tell you about how to properly use a sauna or about the strategic virtues of land mines. I come not to bury the scene in a dense, pedantic explanation – I come to praise it and to offer it my imagination, to embrace and extend it in the most non-proprietary way. My interest is in making the scene mine – and everyone’s. To do so, I will describe a bit about how the scene originated.

The idea of creating an impressive demo that will do something pleasing, playful, and impressive, and that will make use of computing technology, is probably a good bit older than the general-purpose computer. In the early days, it made no sense to divide the category “demo” from that of “game.” Consider the amazing computational project by Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo. This individual, who as part of his day job devised a type of semi-rigid airship that still excites steampunks, created a special-purpose automatic electronic chess player. This system was like the famous mechanical Turk, but with no dwarf inside. Torres y Quevedo’s incredible demo could play a chess endgame perfectly and even had a voice synthesis system – a phonograph – that enabled it to annouce check and checkmate. Since there were no demo parties at the time, his system was permiered at the World’s Fair, in 1914. Possibly the first demo (not on a general-purpose computer, to be sure, but an incredible and impressive demo nonetheless) was executed almost one hundred years ago, and was also possibly the first computer game. If World War I had not ensued the demoscene might have begun in full force the early years of the twentieth century, anticipating and perhaps inspiring general-purpose computers.

There were other demos and other game-demos in the days before the demoscene proper. In the former category were “recreational computing” programs developed at MIT to convert numbers from Arabic numerals to Roman numerals and back and the remarkable joke called “Expensive Typewriter,” which is possibly the first word processor; in the latter were _Tennis for Two,_ perhaps the playful TX-0 demo _Mouse in the Maze,_ and certainly the PDP-1 program _Spacewar._ The scene would have certainly applauded projects like these, along with the work of those who made the line printer produce music and who made pleasing sounds with radio interference on their Altair 8800.

While demos – usually what would be called “wild” demos and would do not fit into any standard demoscene category – abound throughout the twentieth century, the modern-day demoscene has a specific origin. This community, this constellation of creative practice, exists thanks to commercial game software and to the copy protection techniques used on it. The demoscene begins in the confluence of a computer game industry and the impulse to enforce legal restrictions on copying with technical ones. First, certain microcomputer disk drives working in certain modes can be used to _read_ data slightly better than they can _write_ data. Producers of video games – to be honest, not massive horrifying hegemonic corporations, in the early days, but often literaly mom and pop operations such as Sierra On-Line (Ken and Roberta Williams), Scott Adams games, Jordan Mechner, and so on – joined with early videogame publishers to implement so-called _copy protection_ for games delivered on floppy disc.

Copy protected discs could not be copied using the typical methods that one might employ to back up one’s own data. But they could be copied, sometimes using bit copiers with particular parameters and sometimes thanks to the efforts of early digital preservationists who performed an operation upon them known as _cracking_. By reverse-engineering these games and their protection schemes, and by twiddling a few bytes, crackers were able to liberate copy-protected games and allow ordinary users to make the legitimate backup copies to which they were entitled. While I was content to sector-edit my Apple II discs and change my _Bard’s Tale_ characters to have abilities of all 99s, and satisfied myself with placing my Apple //e and my duodrive and monitor in the trunk of my car and heading off to a copying party where warez could flow “the last mile” to end users, others, fortunately, did the difficult and elite work of liberating games in the first place.

This was another time, you understand – 1983-84 – and we had not recieved Bill Gates’s open letter to hobbyists that, had we read it, would have explained to us that we were stealing software. People would have ceased to crack and copy software if they knew that they were killing the game industry. And all the home computer software that is available and runnable today _only_ in cracked versions – now that the companies that were responsible for such software are gone completely or are nothing but a few confused lines on legal documents – all that software would be gone, immolated, left on the ash heap of history, like tears in rain.

But I am not discussing guilt, innocence, or disappearance; I am mentioning how the demoscene came to be. This activity of cracking software led those who were removing copy protection to enhance the software they were dealing with in certain ways. It was possible to tidy programs up and compress them a bit for easier copying. (This tradition is alive and well in many circles, including even electronic literature. Jim Andrews told the story at the Modern Language Association electronic literature reading of how, when one of his works was being translated into Finnish, Marko Niemi returned not only the translation but also a version of his program that was bug-fixed and tidied up.) If there was a little space on the disc, either to begin with or as a result of this compression, one could add a sort of splash screen that credited those who did the cracking and that pilloried the crackers’ enemies.

This sort of crack screen or “intro” to the game has to fit in a small amount of space; it was sometimes a static image, sometimes animated. Most importantly, it was the mustard seed that grew into the various elaborate productions of the demoscene, almost always non-interactive and no longer introducing any commercial game. Rather, the intros and longer demos that are shown nowadays, like the graphics and chiptunes that are also featured at demo parties, are there for their own sake. They do not introduce games, they do not introduce and flog new technologies, they simply demonstrate, or show, purely. Initially, they demonstrated one trick or a series of tricks tied together by very little – perhaps music, perhaps a certain graphical style. Now, in the era of design, demos tend to offer unity rather than units and often treat a theme, portray subjects, evoke a situation or narrative.

Certainly, the productions I am talking about demonstrate what they demonstrate to a technically adept, pseudonymous audience, groups that assemble or gather at events such as Assembly or the Gathering, mostly in Northern Europe. There are demo parties and parties featuring demos elsewhere, however, such as Block Party in the United States. In Boston, the recently-minted @party even has support from a local arts organization that runs a new media gallery and the Boston Cyberarts Festival.

But enough background; time to figure. The method I have used is not anthropological; I have not gone to ask sceners what they have already clearly said in one book, several articles, and a pair of documentaries. I am instead going to use a method where one talks not to people but to objects, where one reads and interprets specific computational texts. I am going to describe what these demos demonstrate, not technically, or not only technically, but culturally. Mackenzie Wark in his book _Gamer Theory_ argues that games offer us only an atopia, a blank placelessness; the productions of the demoscene, on the other hand, I argue, project utopias – not flawless ones, not ideals beyond critique, but utopias nonetheless. Instead of reading these visions as examples simplistic technofuturism devised by Pollyannas, I look at them as imagining new possibilities.

[I showed three demos running on a borrwed Windows computer – thanks to the conference organizers – and then showed them again without sound, discussing each of them.]

### 3. Computer Candy Overload

Gamers and sceners have often come to the same events — for instance, to Finland’s famous Assembly, up until 2007, when the event split into a gamer-oriented winter gathering here in Tampere and a scener-oriented summer one in Helsinki.

Let’s wait for this to explode …

This demo offers a great deal of junk food, of candy canes. Christmas in July, or, more precisely, in August. We progress, if it’s right to call it progress, backwards – in a retro-grade motion, powering into the past with today’s technology.

The demo we are now experiencing, “Computer Candy Overload” by United, is a special type of production that serves to invite people to an upcoming demo party. It advertises Summer Assembly 2010, of course, but is also an interesting starting point for discussion because it has many typical elements of modern-day demos, showcasing certain technical feats while being brought together by a contemporary concept of design. It took first place at @party the first year of that event, in 2010.

In this part of the demo, the flying clusters of objects that were seen earlier are still hurlting backwards through the air, but now, a generated city – an immense city, like a planar version of Issac Asimov’s planet-wide Trantor – is not only scrolling by as we fly backwards above it. The city is also rocking out, pulsing with the beat of the music, as much character as setting. The city, and then the planet.

Now, the direct address to @party, where this demo was released …

Now, the shout-outs, the naming of the most famous demoscene groups that will show themselves, and show their productions, at Assembly …

The shapes of the city again, first radial, then rotating on cubes …

This demo also offers us a flatted female image, a silhouette of the stereotypical hot chick licking a 9 volt battery – bringing together adolescent erotocism with, perhaps a titilating adolescent memory of a a literally electric encouter. To some, it could suggest that a woman can contribute approximately one bit, or one tongue, to the activities of the demoscene – that women can be at best mascots.

That would be an antagonistic reading, but consider that the cyborg-like woman is turning the industrial product of the battery from its intended use in consumer goods to the purpose of sensory stimulation. She is entering into an aesthetic relationship with this compact power source. And, as her image appears on row after row of homogenous computer monitors, she turns the banal laboratory and the corporate workplace into the creative frenzy of the demo party.

### 4. fr-025: the.popular.demo

[An anti-virus warning came up at this point – the demo had been identified as a dangerous program. With the help of Finnish-speakers, I indicated that the computer should run the program.]

As game companies outsource the production of full motion video to pad their products with pre-rendered cutscenes, the demoscene, interested in “the art of real-time,” insists on rendering during execution and limits precalculation. This real-time quality is present in all demos, including the one shown earlier and the one other demo I will show. This one, “The Popular Demo” by farbrausch, was the 1st place PC demo from Breakpoint 2003. Yes, everything you see was produced by almost ten-year-old code, code that is practically classic.

Again, a reading that takes note of gender is interesting. Here we have an exuberant, highly reflective dancing figure. This dancing figure becomes first a trio of dancers and then a crowd. And this crowd, even if the original figure is slightly androgynous, is a crowd of dancing guys, relfecting not only the light but the typical almost entirely male demo party. Actually, the figure seems to me to be male because of the silvery Jockey shorts he is wearing.

We could chastise the demoscene for its lack of inclusiveness and for its occasional sexualization of women, but compare these demos to the recently released trailer for the videogame _Hitman Absolution,_ in which a group of women dressed as nuns casts off their habits, is seen to be wearing sluttly attire and sporting weapons, and then, after attacking the extremely bad-ass hitman, go on to be slaughtered one by one in gruesome detail. This trailer is not really that innovative in the area of violence against women — it simply conflates numerous action-movie clichés. But it still makes a much worse impression than demoscene productions do, because these productions are not, ultimately, about dominance and sadism. Demoscene productions are about exuberance, about abundance, about harmony. If they overlook or slight women now and then, this is a failing that should be remedied. It is one that can be remedies without altering the core dynamic of the scene and of productions.

Demoscene productions can be dark at times, but even when they are more industrial or grim, they are about elements working together and in sync. There is no player being thwarted by the stutter-step of the attacking computer, no need to break the pattern – only a pleasing spectacle, a dance of color and computation, a dance that results from the connection between coder and computation.

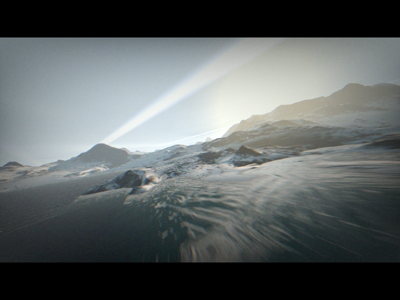

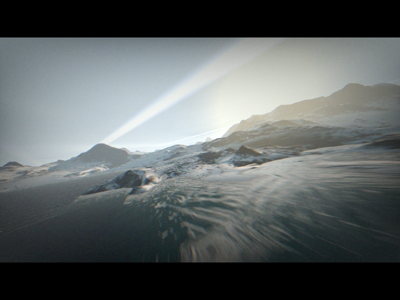

### 5. Elevated

[As I was starting this one, a conference organizer said “please! The lowest resolution! This one is very demanding!”]

As games become more and more extensive in terms of assets and total program and data size, the demoscene flies into smaller and smaller pockets of inner space, creating self-contained 64K demos and 4K intros that run on standard operating systems – one scener, Viznut, even described in late 2011 how “256 bytes is becoming the new 4K.” Viznut, by the way, is from a country that starts with F, where people still smoke a reasonable number of cigarettes, that is not France. Viznut’s recent work has been to creating a 16-byte VIC-20 demo and to develop numerous very short C programs that generate music when their text output is redirected to /dev/audio.

The demo, or more precisely, intro that we are watching now is considerably larger, although all the code for it will comfortably and legibly fit on the screen. This is “elevated” by Rgba & TBC, the 1st place 4k Windows intro from Breakpoint 2009.

Notice the highly mannered, highly artificial way that the so-called camera (completely a second-order construction of the code, of course), calling attention to itself constantly, moves over this model of the natual world, this landscape. The landscape itself approaches the sublime, but the musical score and the movement and cutting work against that sublimity at least as much as they work to evoke it. And what could cut against the sublime more strongly that these beams of light, emanating as if from a club, or several clubs, calling the viewer to think of the music as diegetic, to imagine it happening on this alternate Earth.

Just as the city pulsed to the beat in “Computer Candy Overload,” just as the planet itself did, here the landscape remains static but emits these club-like clarions of light. The terrain itself is part of the party, nature blended with man without being violated. The elevated landscape is augmented without being touched so it can also kick out the jams.

### 6. Platform Studies & _10 PRINT_

A notable distinction between the demoscene and gaming is seen in their relationship to platform. Demoscene productions celebrate and explore the different capabilities of specific platforms, old and new, while the pressures of the market compel cross-platform game development, the smoothing over of platform differences, and the abandonment of older platforms. I don’t mean to say that game developers themselves aren’t aware of the differences between a mobile phone and a desktop, or even between an XBox 360 and a PC, which have very similar hardware but are distinct, for many reasons, as platforms. I simply mean that the impulse in game development is to try to smooth over the differences between platforms as much as possible, while those in the demoscene seek to explore and exploit particular platforms, showcasing their differences.

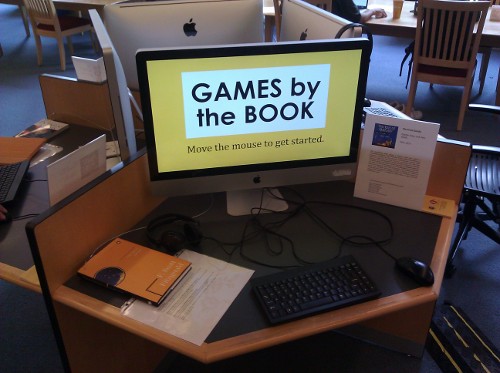

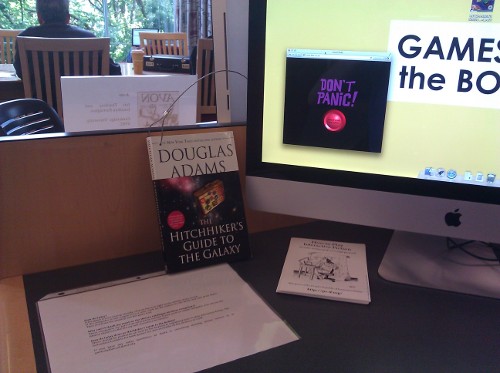

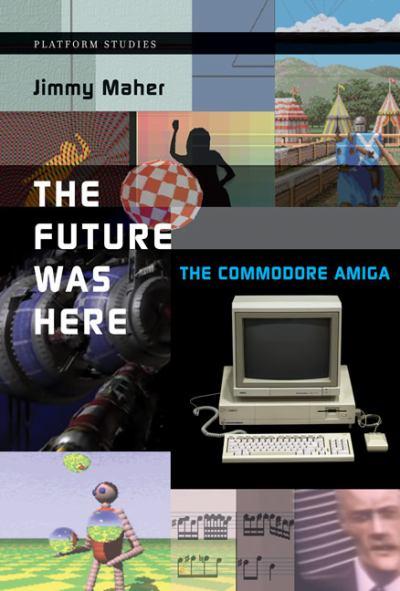

Ian Bogost and I have developed an approach to digital media that follows the demoscene in its concern for particular platforms, what they can and cannot do, and what their construction and use has to say about computing and culture. The approach is called platform studies, and book-length scholarly works using this approach are now being published in the Platform Studies series of the MIT Press.

_Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System_ by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost is the first book in this series. … The second book is _Codename Revolution: The Nintendo Wii Platform_ by Steven E. Jones and George K. Thiruvathukal … The third book in the Platform Studies series is _The Future Was Here: The Commodore Amiga_ by Jimmy Maher …

In November, the MIT Press will print my next collaboratively-written book, which will be part of a different but related series – the Software Studies series. This book is _10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10_ by Nick Montfort, Patsy Baudoin, John Bell, Ian Bogost, Jeremy Douglass, Mark C. Marino, Michael Mateas, Casey Reas, Mark Sample, and Noah Vawter. You may have noticed that the title is practically unpronounceable and impossible to remember, and that the list of authors – there are ten of us – is also impossible to remember. We call the book _10 PRINT,_ and if you remember that you should be able to find out about it.

The book is an intensive and extensive reading, in a single voice, of the one-line Commodore 64 BASIC program that gives it its title. It is a transverse study of how this program functions, signifies, and connotes at the levels of reception, interface, form and function, code, and platform, considering both the BASIC language and the Commodore 64 as platforms. We discuss the relationship of randomness to regularity in this program and in computing, with one chapter devoted to randomness and one to various types of regularity, including the grid and iteration. We trace the academic origins and entrepreneurial implementation of BASIC for the Commodore 64, a programming language that was customized for the Commodore 64 by Ric Weiland and originally written for the 6502 processor by none other than Bill Gates himself. And we explain how the Commodore 64 shared features with other microcomputers of its time and was also distinct from them.

_10 PRINT_ is not a book about games, nor a game studies book, but it is a book that discusses computer games and relates them to another area of creative computing, hobbyist programming. The _10 PRINT_ program itself is neither a game nor a demo, but the book discusses the demoscene about as much as it does gaming, situating the practice of programming and sharing one-liners among these other practices.

The Library of Congress has assigned a call number for this book that places it among manuals for the BASIC programming language, so perhaps the book will be not only hard to recall by title and author but also hard to locate in libraries. It should be easy to read in another way, however, because like the demos I have been showing and discussing, like the 10 PRINT program, the _10 PRINT_ book will be made available online for free. The elite will want to purchase the beautiful physical object, a two-color book with custom endpapers designed by Casey Reas, the co-creator of Processing – but we make scholarship for the masses, not the classes.

But enough about books. Welcome back to the world of the scener, a world of parties, a world of exploring computation and the surprising abilities of specific platforms, a society of the spectacle that everyone can make. Here in the world of the scener, we are all equal and we are all totally elite. Think about a few questions this raises: Should your scholarship be distributed under the gamer model or the scener model? Are games all that can be done with computers, the only productions worth study, commentary, theorizing, and intellectual effort? I’m not inviting you to the next Assembly. I’m inviting us to see creative computing for what it is, something that includes videogames alongside hobbyist computing alongside digital art alongside electronic literature alongside the demoscene. Some of you know that it can be done, some believe that it can be done – so, a shout-out to you. And thanks to everyone for listening.

_The three demos I discussed are all available in executable form at pouet.net, which I have linked to and from which I have appropriated the three images. There is video documentation of them linked there, too._