I discuss the history and context of electronic literature in this article about the new digital novel The Silent History. The article, by Eugenia Williamson, appears in Saturday’s print edition of the Boston Globe.

The Silent History certainly looks like a compelling project.

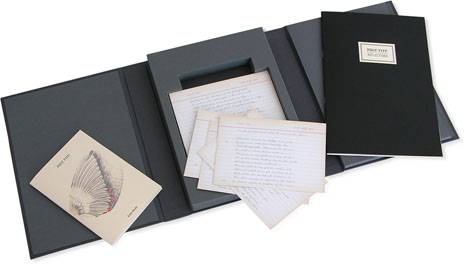

Another just-released digital novel which is also quite compelling, although it doesn’t have the same PR apparatus behind it, is Queerskins by Illya Szilak, designed by Cyril Tsiboulski. Although I’ve not read a great deal of this new novel yet, I’m impressed by its multimedia and literary engagement with a difficult aspect of recent American experience.

Queerskins explores the nature of love and justice through the story of a young gay physician from a rural Midwestern Catholic family who dies of AIDS at the start of the epidemic. Queerskins’ interface consists of layers of sound, text, and image that users can navigate at random or experience as a series of multimedia collages. Images of the mythic and the everyday, the sacred and the profane, from banal vacation footage to vintage burlesque, interact rhizomatically with text and audio monologues to subvert preconceived notions of gender, sexuality, and morality.

Queerskins can be read online for free, and it can be reading using free software; an iPad is not required. Although I’m a fan of location-based and other innovation and respect those working on all sorts of platforms, what I’d like for the future of literature is for it to be like this – fully accessible on even a public library computer and Internet-connected laptops throughout the world.