Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak November;

And each separate bit and pixel wrought a novel on GitHub.

April may be the cruelest month, and now the month associated with poetry, but November is the month associated with novel-writing, via NaNoWriMo, National Novel Writing Month. Now, thanks to an offhand comment by Darius Kazemi and the work of Hugo van Kemenade, November is also associated with the computer-generation of novels, broadly speaking. Any computer program and its 50,000 word+ output qualifies as an entry in NaNoGenMo, National Novel Generation Month.

NaNoGenMo does have a sort of barrier to entry: People often think they have to do something elaborate, despite anyone being explicitly allowed to produce a novel consisting entirely of meows. Those new to NaNoGenMo may look up to, for instance, the amazingly talented Ross Goodwin. In his own attempt to further climate change, he decided to code up an energy-intensive GPT-2 text generator while flying on a commercial jet. You’d think that for his next trick this guy might hop in a car, take a road trip, and generate a novel using a LSTM RNN! Those who look up so such efforts — and it’s hard not to, when they’re conducted at 30,000 feet and also quite clever — might end up thinking that computer-generated novels must use complex code and masses of data.

And yet, there is so much that can be done with simple programs that consume very little energy and can be fully understood by their programmers and others.

Because of this, I have recently announced Nano-NaNoGenMo. On Mastodon and Twitter (using #NNNGM) I have declared that November will also be the month in which people write computer programs that are at most 256 characters, and which generate 50,000 word or more novels. These can use Project Gutenberg files, as they are named on that site, as input. Or, they can run without using any input.

I have produced three Nano-NaNoGenMo (or #NNNGM) entries for 2019. In addition to being not very taxing computationally, one of these happens to have been written on an extremely energy-efficient electric train. Here they are. I won’t gloss each one, but I will provide a few comments on each, along with the full code for you to look at right in this blog post, and with links to both bash shell script files and the final output.

OB-DCK; or, THE (SELFLESS) WHALE

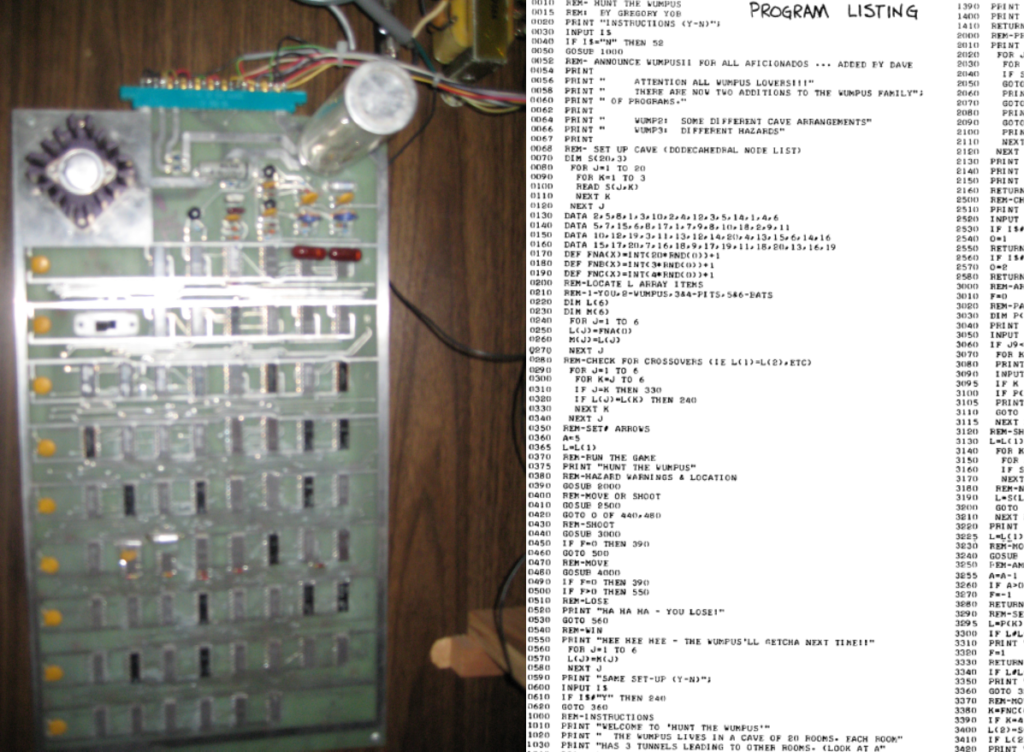

perl -0pe 's/.?K/**/s;s/MOBY(.)DI/OB$1D/g;s/D.r/Nick Montfort/;s/E W/E (SELFLESS) W/g;s/\b(I ?|me|my|myself|am|us|we|our|ourselves)\b//gi;s/\r\n\r\n//g;s/\r\n/ /g;s//\n\n/g;s/ +/ /g;s/(“?) ([,.;:]?)/$1$2/g;s/\nEnd .//s’ 2701-0.txt #NNNGM

WordPress has mangled this code despite it being in a code element; Use the following link to obtain a runnable version of it:

OB-DCK; or, THE (SELFLESS) WHALE code

OB DCK; or, THE (SELFLESS) WHALE, the novel

The program, performing a simple regular expression substitution, removes all first-person pronouns from Moby-Dick. Indeed, OB-DCK is “MOBY-DICK” with “MY” removed from MOBY and “I” from DICK. Chapter 1 begins:

Call Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in purse, and nothing particular to interest on shore, thought would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever find growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in soul; whenever find involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral meet; and especially whenever hypos get such an upper hand of , that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, account it high time to get to sea as soon as can. This is substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with .

Because Ishmael is removed as the “I” of the story, on a grammatical level there is (spoiler alert!) no human at all left at the end of book.

consequence

perl -e 'sub n{(unpack"(A4)*","backbodybookcasedoorfacefacthandheadhomelifenamepartplayroomsidetimeweekwordworkyear")[rand 21]}print"consequence\nNick Montfort\n\na beginning";for(;$i<12500;$i++){print" & so a ".n;if(rand()<.6){print n}}print".\n"' #NNNGM

Using compounding of the sort found in my computer-generated long poem The Truelist and my “ppg 256-3,” this presents a sequence of things — sometimes formed from a single very common four-letter word, sometimes from two combined — that, it is stated, somehow follow from each other:

a beginning & so a name & so a fact & so a case & so a bookdoor & so a head & so a factwork & so a sidelife & so a door & so a door & so a factback & so a backplay & so a name & so a facebook & so a lifecase & so a partpart & so a hand & so a bookname & so a face & so a homeyear & so a bookfact & so a book & so a hand & so a head & so a headhead & so a book & so a face & so a namename & so a life & so a hand & so a side & so a time & so a yearname & so a backface & so a headface & so a headweek & so a headside & so a bookface & so a bookhome & so a lifedoor & so a bookyear & so a workback & so a room & so a face & so a body & so a faceweek & so a sidecase & so a time & so a body & so a fact […]

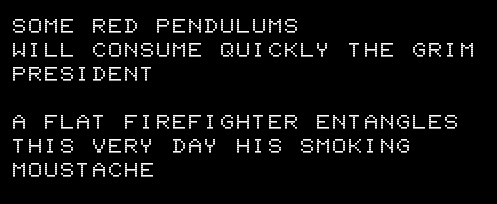

Too Much Help at Once

python -c "help('topics')" | python -c "import sys;print('Too Much Help at Once\nNick Montfort');[i for i in sorted(''.join(sys.stdin.readlines()[3:]).split()) if print('\n'+i+'\n') or help(i)]" #NNNGM

Too Much Help at Once, the novel

The program looks up all the help topics provided within the (usually interactive) help system inside Python itself. Then, it asks for help on everything, in alphabetical order, producing 70k+ words of text, according the GNU utility wc. The novel that results is, of course, an appropriation of text others have written; it arranges but doesn’t even transform that text. To me, however, it does have some meaning. Too Much Help at Once models one classic mistake that beginning programmers can make: Thinking that it’s somehow useful to read comprehensively about programming, or about a programming language, rather than actually using that programming language and writing some programs. Here’s the very beginning:

Too Much Help at Once

Nick MontfortASSERTION

The “assert” statement

**********************Assert statements are a convenient way to insert debugging assertions

into a program:assert_stmt ::= “assert” expression [“,” expression]

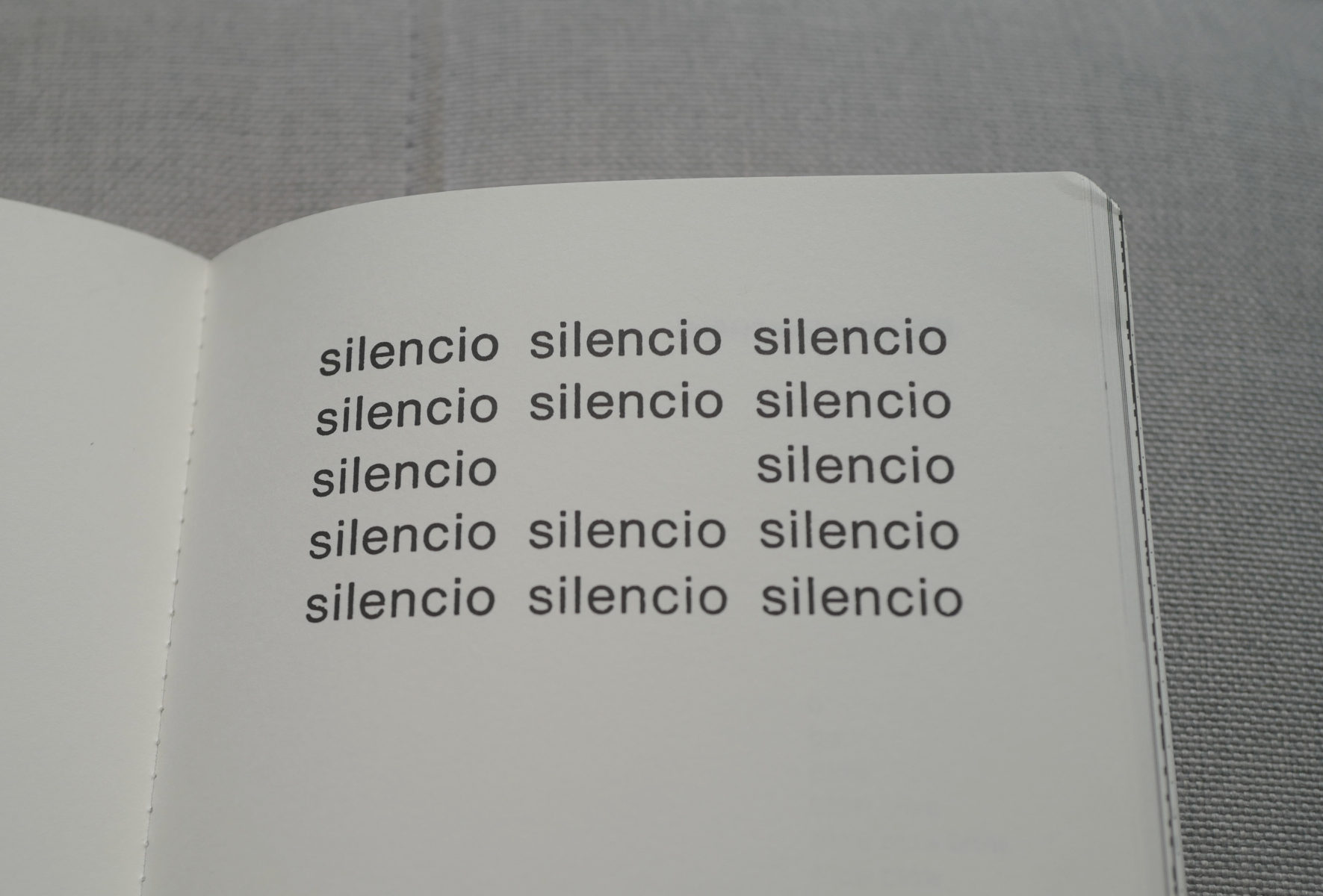

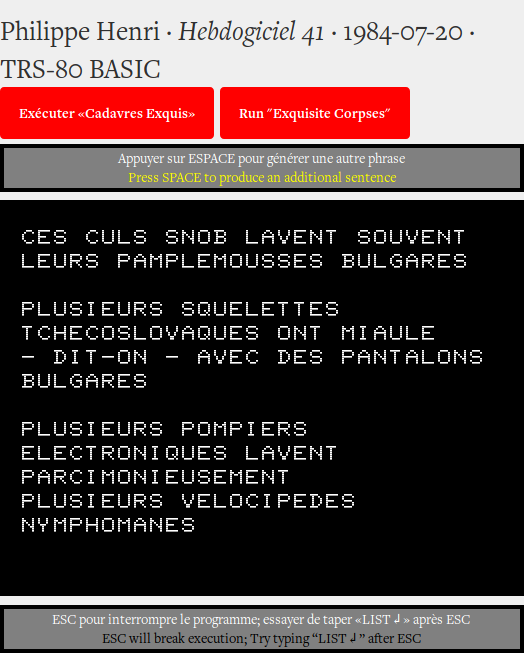

A plot

So far I have noted one other #NNNGM entry, A plot by Milton Läufer, which I am reproducing here in corrected form, according to the author’s note:

perl -e 'sub n{(split/ /,"wedding murder suspicion birth hunt jealousy death party tension banishment trial verdict treason fight crush friendship trip loss")[rand 17]}print"A plot\nMilton Läufer\n\n";for(;$i<12500;$i++){print" and then a ".n}print".\n"'

Related in structure to consequence, but with words of varying length that do not compound, Läufer’s novel winds through not four weddings and a funeral, but about, in expectation, 735 weddings and 735 murders in addition to 735 deaths, leaving us to ponder the meaning of “a crush” when it occurs in different contexts:

and then a wedding and then a murder and then a trip and then a hunt and then a crush and then a trip and then a death and then a murder and then a trip and then a fight and then a treason and then a fight and then a crush and then a fight and then a friendship and then a murder and then a wedding and then a friendship and then a suspicion and then a party and then a treason and then a birth and then a treason and then a tension and then a birth and then a hunt and then a friendship and then a trip and then a wedding and then a birth and then a death and then a death and then a wedding and then a treason and then a suspicion and then a birth and then a jealousy and then a trip and then a jealousy and then a party and then a tension and then a tension and then a trip and then a treason and then a crush and then a death and then a banishment […]

Share, enjoy, and please participate by adding your Nano-NaNoGenMo entries as NaNoGenMo entries (via the GitHub site) and by tooting & tweeting them!