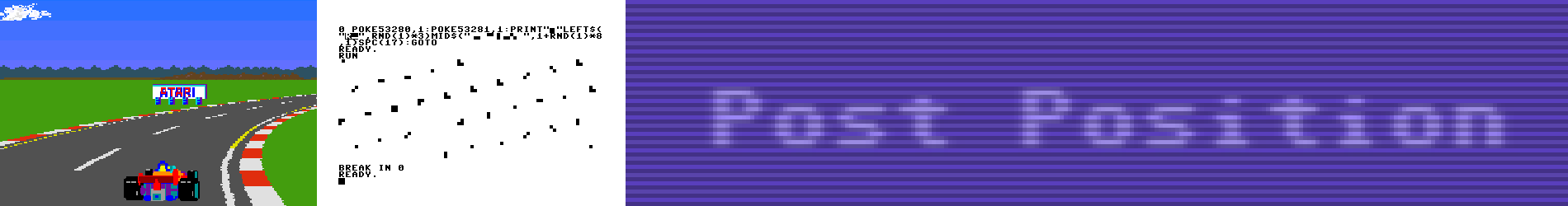

During Synchrony 2019, on the train from New York City to Montreal, two of us (nom de nom and shifty) wrote a 64 byte Commodore 64 program which ended up in the Old School competition. (It could have also gone into the Nano competition for <=256 byte productions.) Our Alphabit edged out the one other fine entry in Old School, a Sega Genesis production by MopeDude also written on the train.

The small program we wrote is not a conventional or spectacular demo; like almost all of the work by nom de nom, it uses character graphics exclusively. But since we like sizecoding on the Commodore 64, we wanted to explain this small program byte by byte. We hope this explanation will be understandable to interested people who know how to program, even if they may not have much assembly or C64 experience.

To get Alphabit itself, download the program from nickm.com and run it in a C64 emulator or on some hardware Commodore 64. You can see a short video of Alphabit running on Commodore 64 and CRT monitor, for the first few seconds, for purposes of illustration.

these bytes load

at: 02 08 01 00 00 9E 32 30

$0808 36 31 00 00 00 20 81 FF

$0810 C8 8C 12 D4 8C 14 D4 C8

$0818 8C 20 D0 AD 12 D0 9D F4

$0820 D3 8C 18 D4 D0 F5 8A 8E

$0828 0F D4 AE 1B D4 E0 F0 B0

$0830 F6 9D 90 05 9D 90 D9 AA

$0838 88 D0 E0 E8 E0 1B D0 DB

Load address. Commodore 64 programs (PRG files) have a very simple format: a two-byte load address, least significant byte first, followed by the machine code which will be loaded at that address. So this part of the file says to load at $0802. The BASIC program area begins at $0801, but as explained next, it’s possible to cheat and load the program one byte higher in memory, saving one byte in the PRG file.

BASIC bootloader, $0802–$080c: This program starts with a tiny BASIC program that will run when the user types RUN and presses ENTER. When run, this program, a bootloader, will execute the main machine code. In this case the program is “0 SYS2061” with the line number represented as 00 00, the BASIC keyword SYS represented by a single byte, 9E, and its argument “2061” represented by ASCII-encoded digits: 32 30 36 31. When run, this starts the machine code program at decimal address 2061, which is $080D, the beginning of the next block of bytes.

Advanced note: Normally a BASIC program would need at least one more byte, because two bytes at $0801 and $0802 are needed to declare the “next line number.” You would have to specify where to go after the first line has finished executing. But for our bootloader, any non-null next line number will work as the next line number. Our program is going to run the machine code at $080d (decimal 2061) and then break. So we only need to fulfill one formal requirement: Some nonzero value has to be written to either $0801 or $0802. For our purposes, whatever is already in $0801 can stay there. That’s what allows this program to load at $0802, saving us one byte.

On the 6502: There are three “variables” provided by this processor, the accumulator (a general-purpose register, which can be used with arithmetic operations) and the x and y registers (essentially counters, which can be incremented and decremented).

Initialization, $080d–$081a: This sets up two aspects of the demo, sound and graphics. Actually, after voice 3 is initialized, it is used not only to make sound, but also to generate random numbers for putting characters on screen. This is a special facility of the C64’s sound chip; when voice 3 is set to generate noise, one can also retrieve random numbers from the chip.

ldy #$85), the program can simply increment y (iny), which takes only one byte. After storing $85 in those two registers, the goal is to set the border color to the same as the default screen color, dark blue, $06. Actually any value with 6 for a second hex digit will work, so again the program can increment y to make it $86 and then use this to set the border color. Finally, the y register is going to count down the number of times each letter (A, B, C … until Z) will be written onto the screen. Initially, the program puts ‘A’ on screen $86 times (134 decimal); for every subsequent letter, it puts the letter on screen 256 times — but that comes later. The original assembly for this initialization: iny ; $85 works for the next two...

sty $d412 ; voice 3 noise waveform

sty $d414 ; voice 3 SR

iny ; $86 works; low nybble needs to be $6

sty $d020 ; set the border color to dark blue

Fortunately, the x register already is set up with $01, the screen code of the letter ‘A’, thanks to SCINIT. In this loop, the value of the current raster line (the lowest 8 bits of a 9-bit value, to be precise) is loaded into the accumulator. The next instruction stores that value in a memory location indexed by x; as x increases during the run of the program, this memory location will eventually be mapped to the sound chip registers for voices 1 and 2, starting at $d400, and this will make some sounds. This is what gives some higher-level structure to the sound in the piece, which would otherwise be completely repetitive. After this instruction, however many characters are left to put onto the screen (counting down from 255 to 0) goes into the volume register, which causes the volume to quickly drop and then spike to create a rhythmic effect. With the noise turned on it makes a percussive sound. All of this takes place again and again until that raster line value is 0, which happens twice per frame, 120 times a second.

raster:

lda $d012 ; get raster line (lowest 8 bits)

sta $d3f4,x ; raster line --> some sound register

sty $d418 ; # of chars left to write --> volume

bne raster

txa

random:

stx $d40f ; current letter --> freq

ldx $d41b ; get random byte from voice 3

cpx #240

bcs random

sta $0590,x ; jam the current letter on screen

sta $d990,x ; make some colors with the value

tax

dey

bne raster

brk as part of this PRG, but hey, this is a 64-byte demo with a BASIC bootloader, written one day on a train. If the program has more letters to go through, it branches all the way back up to the beginning of the “each letter loop.” inx

cpx #27 ; have we gotten past ‘Z’?

bne raster