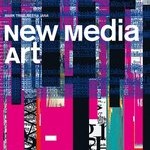

Here’s a nice slice of recent digital art – online, in performance, and installed – expertly introduced. The book is well-illustrated (no surprise from this publisher) and has a welcome emphasis on the computational. Sure, some of the purest pieces of software art (Galloway’s fork bomb, obfuscated code, and the like) aren’t mentioned, but port scanning, packet sniffing, and the glitchy transformation of HTML are all represented. As with all Basic Genre Series books, there’s an introduction followed by page spreads, each on a single work. The format has its pros and cons, but the results, in this case, certainly offer a nice adjunct to Christiane Paul’s similarly introductory book, Digital Art. The engagement of artists with social issues, the critique of technology, video gaming, and free software are particularly evident in New Media Art. And, how great that Super Mario Clouds and the work of Jodi now sit on the shelf beside books on abstract expressionism, Greek art, and the still life.

Pablo Gervás to Speak at MIT

Next week, the Purple Blurb series offers a special talk by a leading European researcher in creative text generation.

Pablo Gervás works as associate professor (profesor titular de universidad) at the Departamento de Ingeniería del Software e Inteligencia Artificial, Facultad de Informática, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. He is the director of the NIL research group and also of the Instituto de Tecnología del Conocimiento.

His research is on processing natural language input, generating natural language output, building resources for related tasks, and generating stories. In the area of creative text generation, he has done work on automatically generating metaphors, formal poetry, and short films.

He will speak on Wednesday May 20, 6pm-7pm, at MIT in room 14E-310. The talk is (as with all Purple Blurb presentations) open to the public, and (as with all Purple Blurb presentations so far) will be in English.

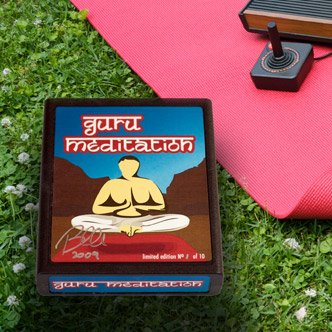

Guru Meditation

Ian Bogost has just released his new game Guru Meditation for two platforms: Atari VCS and iPhone. Yes, really. The game is a reimplementation – a reimagining – of an in-house game created at Amiga, the developers of the Wii Fit’s granddaddy, the Joyboard. The iPhone game is 99¢; the object d’atari, which includes a console, Joyboard controller, yoga mat, and cartridge, is sure to be a bit more dear. (The price is available upon request.) But if it’s the only thing in the world that will lead you to your center … why not?

Cheating

Two main methodologies are used in Cheating to understand how and why people cheat at video games. The first is the analysis of how print publications and devices surrounding games (Nintendo Power, strategy guides, the Game Genie, and the like) help to shape our concept of these games, providing the axes along which they can be evaluated and how they should be played. Next, Consalvo interviews gamers and explores an MMO to find out what players consider cheating and what boundaries they draw as they play. What results is some real insight into single-player and multiplayer cheating and into various corporate, industrial, and legal perspectives as well as those of individual players. The book does not work toward a single definition of cheating; rather, it shows how players and game-makers are actively negotiating what’s fair and what isn’t, working to allow the enjoyment of the game, to map or adapt “real-life” ethics into the magic circle, and to build the gaming equivalent of cultural capital.

Children of Arcadia

In Cambridge’s City Hall Annex, Children of Arcadia provides a wide vista onto a virtual world as well as a station for interacting. A visitor can guide a female character to different parts of the landscape. The pastoral scene, with the ruins of Wall Street buildings scattered about, features weather and other atmospheric effects that are keyed to current financial conditions. Plummeting stock prices seem to manifest themselves in darkness, rain, and billowing columns of smoke. Bullish markets would lead to sun and clear skies. Steering an avatar through this world could be more enjoyable. It seems that the character can’t affect anything or interact with other wanderers. Still, the view of the landscape and the connection to real-time data makes for a powerful, relevant image and works well in the installation context. The economic crisis is found “in arcadia” here, where the helplessness of the steerable characters is at least appropriate.

Violet

At long last, this is a discussion – a review, of sorts – of Violet, an interactive fiction piece by Jeremy Freese. It isn’t the sort of review that tells you whether or not you should go play the game. Violet is an excellent game, and if you’ve been waiting on my recommendation, spongemuffin, you’ve been silly. It won the 2008 IF Comp along with four XYZZY awards, including Best Game. Go play it if you haven’t. If you have, read on for my mildly spoilery but hopefully incisive comments.

Spoilers

As you know if you’re reading the text in this box, Violet is a game in which you try to defeat distraction and work on your dissertation. The things that happen in the simulated world are narrated to you by the (imaginary) voice of your Australian girlfriend, Violet. While Violet won the XYZZY award for Best NPC, she isn’t an NPC, at least, any more than Lord Flathead is an NPC in Zork. She’s a narrator, and her narration is both lively for its own sake (filled with hilarious and diverse pet names) and suggestive of a relationship that is meaningful and interestingly textured. For a game with no NPCs at all (in the simulation itself), there is a lot of information being provided about other characters: The PC’s ex, Julia, and the “dork” she is talking to, the zombie horde visible through the window, the former occupant of the office, and of course our erstwhile narrator, Violet. The game shows how other characters can meaningfully manifest themselves even when they don’t do anything in terms of picking up objects, manipulating the state of the world, or serving as an explicit opponent (as the Thief did in Zork) or helper (as Floyd does in Planetfall).

This delights me; Violet is the second IF Comp winner in a row that features very unusual and effective narration. The whole point of my in-development IF system, Curveship, is allow for even more radical and general types of wacky narration. Violet shows that you can do something powerful already, just as hypertext allows you to model and manipulate space, with effort. If there were facilities for narrating provided – the way that there are facilities in IF for modeling objects, containers, action, and so on – it seems to me that significantly more could be done along these lines.

Violet demonstrates that it’s more interesting if the game’s replies vary and have some texture, as one would expect when reading a novel or poem. Even if the difference is just in a pet name, it’s a lot better than nothing, and provides some pleasure to the player. Of course, there’s much more in Violet that amuses: The tone of polite refusals to do certain actions and the recollections of a pleasant relationship and a brilliant personality, all mentioned at suitable moments during the course of ordinary actions.

The characters (again, none of which are simulated) are certainly great elements of Violet. The overall situation is also an interesting one: The PC has to get rid of, rather than acquire, objects, and shut out distraction to focus on a task. There’s the trial that the PC go though, the degradation that goes along with that, and the fitting ending in which the day’s accomplishment reveals a different course of life. The narrative as well as the narration works well.

If there’s anything that’s a bit awkward in Violet, it’s the puzzles themselves. Manipulating objects reveals things about the main relationship in the story, which is nice, but it doesn’t seem to fit into the scheme of the world as powerfully as quotidian actions do in Shade, for instance. There’s a lot of trial and error and mechanical manipulation (of projectiles, of one’s head) that is required. In the end, it’s neither an indication that a profound riddle has been solved or a powerful, revelatory gesture – it’s just showing you the extreme, absurd ends that you shouldn’t be going to.

That’s a minor criticism, though, particularly given the good hint system that is included in the game. And it doesn’t stop the the narrated characters, the overarching situation of the day, and the concluding twist from having their effect. Most of all, Violet shows that brilliant narration can be done in a comp game and can be done in a very different way than Lost Pig did it, and that, in a different way, the joys of reading can work together with those of game playing.

Video Games Tending To Zero

I’ve been interested in testing the lower limits of digital objects, looking at how simple and minimal something can be while still being understood as falling into a fairly familiar category. My ppg256 series, which consists of 256-character Perl poetry generators, is in this vein, as are my attempts at very small stories and poems in forms, “Ten Mobile Texts.” In the realm of sound, Tristan Perich’s One-Bit Music and Shifty’s One-Bit Groovebox are somewhat similar projects that attempt to show that if you bring eight bits, you aren’t bringing eight bits too few – you’re bringing seven too many.

It’s also possible to wonder what the smallest possible video game is, or how to push video games toward minimality. First, let’s take a step back to see what the smallest possible game of any sort might be: The Game, in which one simply tries to avoid thinking of The Game, and, if one does think of the game, one loses. This one’s interesting because it can’t be won. Neither can Space Invaders, of course, but The Game is different: a player can’t even be conscious of playing without losing.

*************** . ***************** 5 **************** . **************** 5 *************** . ***************** 5 ************** .****************** 4 *************** .***************** 4 ************** .****************** 3 ************* .******************* 2 ************** . ****************** 2 *************** . ***************** 2 **************** . **************** 2 *************** .***************** 2 **************** .**************** 2 ***************** .*************** 2 **************** .**************** 2

Somewhat akin to ppg256 and The Game is Jason McIntosh’s obfuscated (or at least very compressed) game fall.pl, a 494-character Perl program in which you plunge down a canyon, inflecting yourself left and right to try to avoid hitting the walls of a canyon, which slant and are unseen until the last moment. fall.pl is made of a very small amount of code, but there are plenty of games with less – Pong, for instance, is simply a circuit and doesn’t have any code. One thing I find interesting about fall.pl and pleasing in some minimal games is the highly abstract nature of the visuals, something also seen in Pong. This Perl game actually has many of Pong‘s luxuries as well, including multiple lives and a report of your score at the end of the game.

Although made up of a whole 1024 bytes each – of assembly – Ian Bogost’s game poems for the Atari VCS incline toward minimality. The most recent entry, Thunderstorm, is a game about watching a thunderstorm and guessing, after a flash of lightning, how long it will take for thunder to sound. Simple as it is, this game uses audio as well as video channels, features color (although rarely), supports two-player competition, and is winnable.

As it has in music, physical computing has weighed in on minimal video gaming. Rob Seward’s three-person Tag is played on a 5×7 LED grid and has been hailed as “the simplest video game in the world.” Interestingly, Clive Thompson goes on to note that Seward’s game Boo is even simpler, with a single light bulb for a display. One player lights the bulb and the other attempts to hit a button as soon as possible afterwards.

There are some things that all of these games have in common: Something surprising happens in all of them, and that surprising thing is critical to the gameplay. Randomness provides the surprise in fall.pl and Thunderstorm. The players provide it in Tag and Boo. A representational excuse (you’re falling into a canyon, we’re watching a storm, got you!) can be used, but it’s the unexpected, not the connection to reality, that makes these games work. And there’s just one last thing to note: I think that surprise even plays an important role in The Game. Ouch … I just lost The Game.

Have You Played Atari Today?

I have been wanting to have some sort of end-of-year fest, however small-scale and short-notice, and I was also looking for an excuse to unpack and reconfigure my office (a.k.a. the Trope Tank) after hauling much of my video game stuff back from the Boston Cyberarts Festival. So I decided to invite some MIT folks over, including CMS and GAMBIT game-players. Excuses to celebrate included this here new blog, Racing the Beam (not so new, but still a good excuse for a party), and MIT’s recent decision to promote and tenure me. I was very pleased to host a contingent from the Literature department, some CMS students and staff, and the person who has kindly loaned me that fine Asteroids cabinet, Jason Scott. There was an emphasis on the Atari VCS at the event. Players battled at Joust (and contemplated the symbology and implications of the game), played Space Invaders as a team, found Barnstorming simple but serene, figured out Yars’ Revenge, grooved with Tempest 2000 on the Jaguar, and failed to beat Ghosts ‘n Goblins on the NES. (Still, that was a lot better than I can do during an offhand attempt, Josh.) Thanks to all who stopped by.

Robot Jams

I heard Ensemble Robot last night at AXIOM. It was a suitably outrageous performance and a nice final event for the 2009 Boston Cyberarts Festival, which officially ends today. Ensemble Robot has robot musicians who play alone and with human performers. Two of them, a robot glockenspiel and a one-string robot instrument/performer, were at AXIOM last night. They played several pieces, including Belle Labs. The final number involved using one of the robots as an instrument, controlled by a MIDI guitar. It was a nice finale that sounded fittingly extreme, but I have to admit that “slaving” this former silicon-based collaborator to a person in this way disturbed me a bit. I also wish that there had been time for questions and discussion, so that I would have a better idea of how autonomous the robots were, if they were listening to the other performers, and so on. In any case, if you have a chance to hear this unusual group, I highly recommend it.

The performance, which included people playing on hacked-together non-electronic instruments, reminded me of the amazing sort of things that used to happen at MITRES, the MIT Electronics Research Society, back when they had their open mic/show and tell nights. I noticed that Ensemble Robot artistic director Christine Southworth is an MIT and Brown alumnus; perhaps the coincidence runs deeper.

Mario and the N64 Platform

Jason Scott, an archivist and documentary-maker who deals with creative computing, gave quite an interesting talk about Super Mario 64 at Notacon 6 in Cleveland on April 17. I believe it’s the first platform studies talk I’ve heard by someone other than Ian Bogost or me. Jason goes into the concept behind platform studies, pimps our book, Racing the Beam (special thanks for that one), and discusses how the substantial achievements and particular design of Super Mario 64 related to the corporate context of the time, the expectations of players, and the Nintendo 64 hardware. This was at an event that is a hacker conference, not an academic one – I hope we academics can keep up in terms of bringing technology and culture together. The talk is almost an hour long, with some questions at the end, and is well worth the bandwith and the time.