About 12 hours ago I was reading “The New Art of Making Books” by Ulises Carrión, a text I’d read before but which I hadn’t fully considered and engaged with. As I thought about Carrión’s writing, I felt compelled to put together a short piece on the Web. That took the form of a Web page containing a rapidly-moving concrete poem. The work I devised is called “Una página de Babel.”

Many will surely note that it is based on Jorge Luis Borges’s “Una biblioteca de Babel” (The Library of Babel). And, I hope people are aware of some the other interesting digital projects based on this story. I have seen one from years ago on CD-ROM; one that is very nice, and available on the Web, is Jeremiah Johnson’s BABEL. There’s also the exquisite Library of Babel by Jonathan Basile.

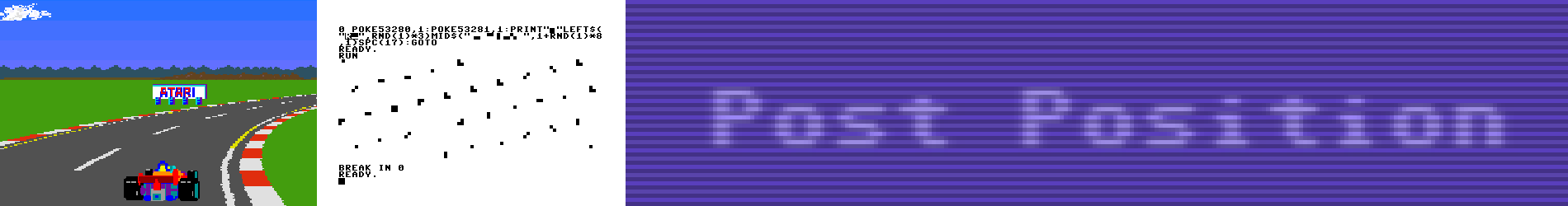

My piece does not try to closely and literally implement the library that Borges described, although it does have a page that is formally like the ones in Borges’s library: 80 characters wide, 40 lines long. Given this austere rectangular regularity, I assumed a typewriter-like monospace font.

The devotion of “Una página” to what the text describes stops there; instead of using the 23-letter alphabet that Borges sketches to populate this 80×40 grid, I use the unigram probabilities of letters in the story itself, in the Spanish text of “La biblioteca de Babel.” So, for instance, the lowercase letter a occurs a bit less than 8.4% of the time, and this is the probability with which it is produced on the page. The same holds for spaces, for the letter ñ, and for all other glyphs; they appear on the page at random, with the same probability that they do in Borges’s story. Because each letter is picked independently at random, the result does not bear much relationship to Spanish or any other human language, in which the occurrence of a glyph usually has something to do with the glyph before it (and before that, and so on).

“Una página” is also non-interactive. One can zoom, screenshot, copy and paste, and so on, but the program itself does not accept user input.

I sketched the program in Python before developing it in JavaScript, and when I was done with the HTML page that includes the JavaScript program, I thought I’d make a Python version, too. But when I did, I was disappointed; the Python program isn’t a page, and doesn’t produce a page, and so doesn’t seem to me to fit the concept, which has to be that of a page. Thus, I’m not going to release the Python program. The JavaScript version is the right one, in this case.