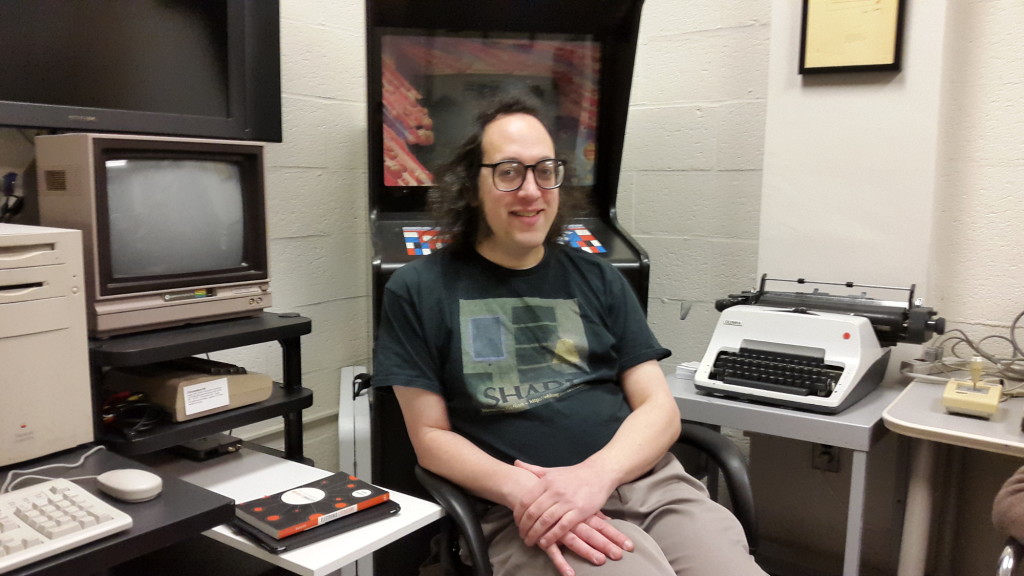

Taper, an online literary magazine published twice yearly, is now in its 12th issue. An independent editorial collective (Kyle Booten, Angela Chang, Kavi Duvvoori, Leonardo Flores, Helen Shewolfe Tseng, and Andy Wallace, for this issue) makes all the decisions about selections, themes for forthcoming issues, and so on, and also handles all communication with authors. They do all the work! Editors are allowed to submit works, in which case they recuse themselves from the collective’s discussion. I’m proud to be publisher of this magazine — although it’s really the editorial collective that makes it happen.

My “Gram’s Fairy Tales” was selected for this issue, with “Tools” as its theme!

For those who haven’t visited Taper, when you do, you’ll find that the poems are computational and are no more than 2KB (2048 bytes) in size. (Issue #1 hosted 1KB poems and issue #3 had ones that were 3KB, but Goldilocks found the ideal constraint in 2KB.) Issue #12 features a lot of general-purpose programs that are true tools, textual or otherwise, as well as dynamic text generators that speak to the theme. In fact, the issue is our largest yet, with 32 selections.

To read what the author/programmers say about their work, in their statements, you generally have to “View Page Source” (or choose the similar option in your browser) and look at a comment at the top of each page, which is licensed as free (libre) software so you can make use of it in any way you like. However, given the theme of this issue, I wrote “Gram’s Fairy Tales” to not only give access to the underlying HTML5, but also to let people write grammars that can be placed in a text area and used to generate stories. Given this, I’m going to pull a bit from my “author statement,” found in complete form in the comments, and post it here. I’ll also provide three novel story grammars written by others: Jhave Jhonston (author of ReRites), Kyle Booten (author of Salon des Fantômes), and Kavi Duvvoori (author of Common Is That They).

Inspirations, Instructions – Jhave’s – Kyle’s – Kavi’s

Two Inspiring Systems, and Instructions

As I developed “Gram’s Fairy Tales,” I was thinking about two remarkable story generation systems, very different ones, both quite simple.

One is the mid-1980s Story Machine, which I’ve known about for a while in its Commodore 64 incarnation. It is a strangely animistic system in which any entity can perform any transitive or intransitive action. While there are multimedia elements and some notion of state, it essentially develops narratives one independent sentence at a time.

The other is a system by Joseph Grimes, operational in Mexico City in 1963. Only one text from this story generator is documented. It seems to have produced stories based on a story grammar, with formalist structures. So, a hero would be challenged in some way and overcome the challenge. The one-page magazine article about the system suggested that it could be called “Grimes’s Fairy Tales.”

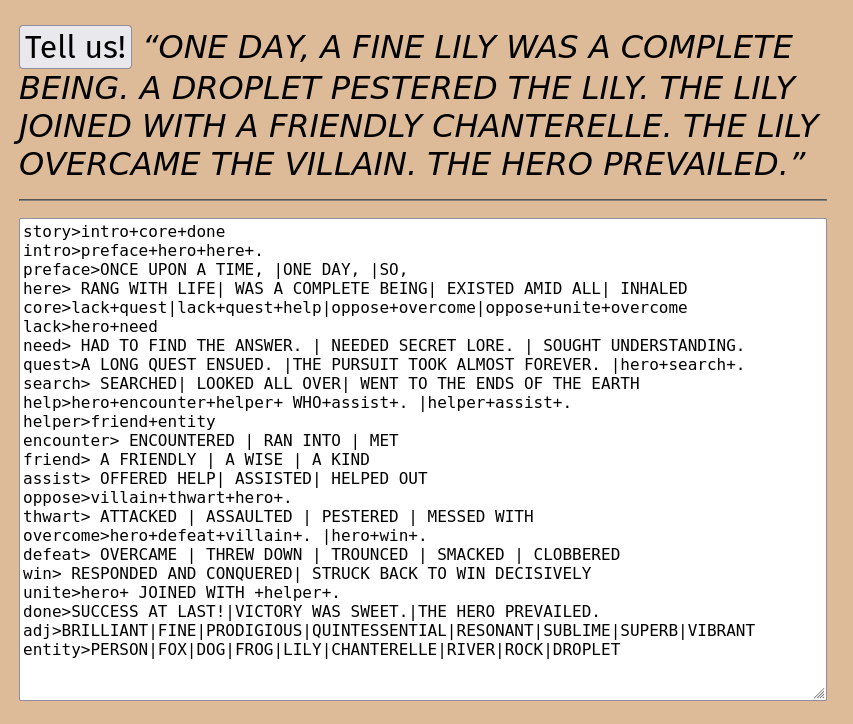

“Gram’s Fairy Tales” uses a simple grammar to generate stories. There are special “hero” and “villain” tokens, which always refer to the same two entities, selected from the “entity” rule. You don’t have a pool of good guys and bad guys; any entities are equally likely to be heroes and villains.

Beyond those special tokens, the other nonterminal tokens (the lowercase ones) expand according to rules, with each represented as one line in the text field.

The “|” indicates alternatives; these are split apart first.

The “+” indicates a conjunction of elements; all of those will appear.

Tokens keep getting expanded until eventually there is a run of text which in my example grammars are in all caps. These are “terminals,” and ends up being presented as is, without any further transformation.

Your grammar needs to begin with a “story” rule, and it should have “adj” and “entity” rules so a hero and villain can be determined. Anything else is up to you. Indeed, you don’t actually have to refer to a hero or villain.

My terminals are in all caps (making for an all-caps story) simply because it’s tricky to get the capitalization of sentences right. It would make things harder for those who want to edit the grammar and create their own stories, and the grammar is already a bit tricky.

Spaces have to be included properly at the beginning and ending of terminals, for instance, except for the terminals that come at the very end of stories.

Also, if you have entities or adjectives that begin with a vowel sound, you’ll end up with grammatical mistakes. The solution in this simple tool (or toy) — simply use adjectives and entities that all begin with consonant sounds!

To get an idea of how to write your own grammar, you may want to start with an extremely simple one, such as:

story>hero+ FOUGHT +villain+.|hero+ TOOK A NAP. adj>CLEVER|STRONG entity>FOX|CHICKEN

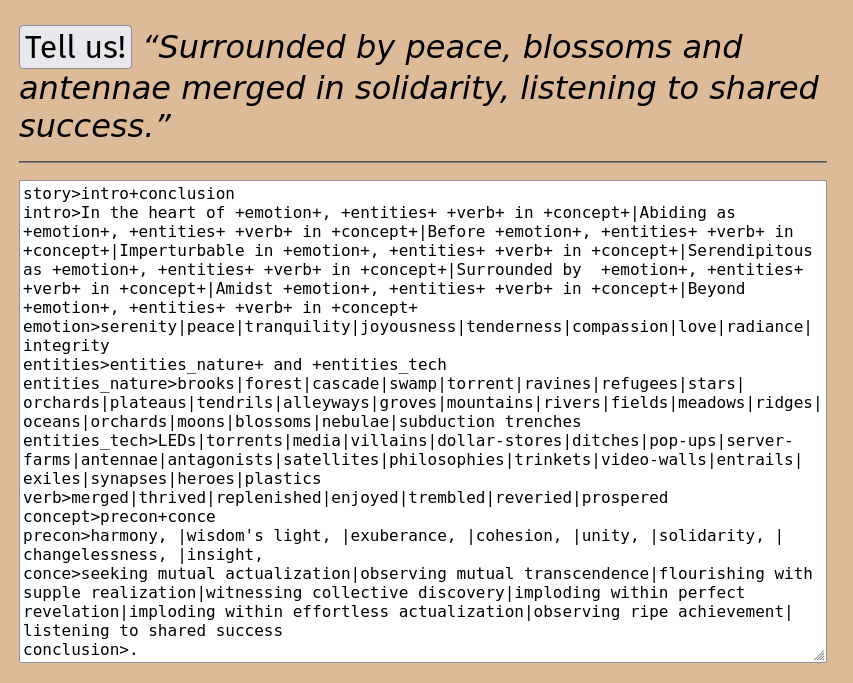

Jhave’s Grammar: A Harmonious Moment

Here’s a striking project by Jhave Johnston, who is my colleague at the University of Bergen Center for Digital Narrative and winner of the Robert Coover Award. You’ll notice that Jhave wrote his grammar to enable proper capitalization, despite the difficulty of that. Although the right side of the text is hidden, you can select it all and paste it into “Gram’s Fairy Tales” to see how it works.

story>intro+conclusion intro>In the heart of +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Abiding as +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Before +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Imperturbable in +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Serendipitous as +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Surrounded by +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Amidst +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+|Beyond +emotion+, +entities+ +verb+ in +concept+ emotion>serenity|peace|tranquility|joyousness|tenderness|compassion|love|radiance|integrity entities>entities_nature+ and +entities_tech entities_nature>brooks|forest|cascade|swamp|torrent|ravines|refugees|stars|orchards|plateaus|tendrils|alleyways|groves|mountains|rivers|fields|meadows|ridges|oceans|orchards|moons|blossoms|nebulae|subduction trenches entities_tech>LEDs|torrents|media|villains|dollar-stores|ditches|pop-ups|server-farms|antennae|antagonists|satellites|philosophies|trinkets|video-walls|entrails|exiles|synapses|heroes|plastics verb>merged|thrived|replenished|enjoyed|trembled|reveried|prospered concept>precon+conce precon>harmony, |wisdom's light, |exuberance, |cohesion, |unity, |solidarity, |changelessness, |insight, conce>seeking mutual actualization|observing mutual transcendence|flourishing with supple realization|witnessing collective discovery|imploding within perfect revelation|imploding within effortless actualization|observing ripe achievement|listening to shared success conclusion>.

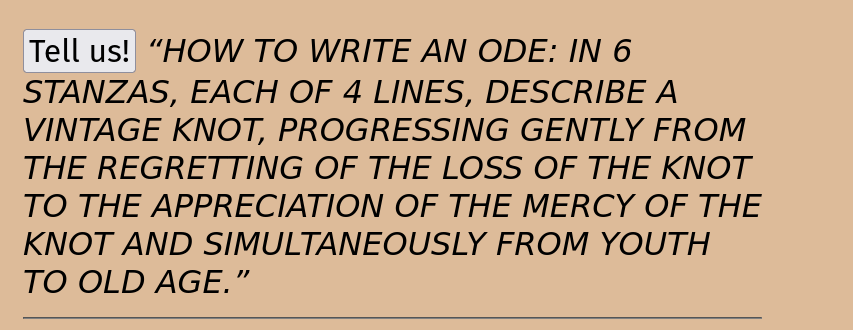

Kyle Booten’s Grammar: How to Compose an Ode

Kyle is a longtime member of the Taper editorial collective — since issue #5 in fall 2020! — and has long been working to have computer text generation provoke his own (and others’) writing. His grammar produces instructions for writing odes of different sorts, and is the most elaborate by far, clocking in at 70 lines, with several that are essentially comments or blank. Again, you can select all of these and paste them into “Gram’s” without trouble, although some of the text on the right side is obscured.

Pindar Horace Hordar (An Ode-Gym) Kyle Booten story>HOW TO WRITE AN ODE: +ode_type ode_type>pindaric|pindaric|pindaric|pindaric|horatian|horatian|horatian|horatian|blended PINDARIC pindaric> ?+strophe+ ?+antistrophe+ ?+epode strophe>IN A STANZA OF +p_lines+ +short_or_long+ +meter1+ LINES, ADOPTING A +style1+ TENOR, DESCRIBE +hero+, WITH PARTICULAR ATTENTION TO THE +p_feature+ OF +hero+. meter1>DACTYLLIC|DACTYLLIC|DACTYLLIC|QUASI-AEOLIC|LOGAOEDIC meter2>meter_adjust+ +meter1|TROCHAIC|IAMBIC meter_adjust>NOT|ANYTHING BUT|ONLY IMPERFECTLY p_lines>6|8|8|10|12 short_or_long>BRIEF|BRIEF|BRIEF|LENGTHY|LENGTHY|LENGTHY|ABSURDLY LONG p_feature>LAUREL|ORDER|VIRTUE|LAW|DECREE|STRENGTH|CRIME|FATE style1>SOLEMN|MYSTICAL|GNOMIC|JAGGED|SUBLIME|MORALISTIC|GOVERNMENTAL|MUSCULAR|LAUDATORY|REVERENT|JUBILANT antistrophe>USING THE SAME STANZAIC STRUCTURE BUT NOW +style_or_mentioning+, CONTRAPOSE +hero+ WITH ITS INVERSE AND ENEMY, +villain+. style_or_mentioning>style2|MENTIONING +p_trait style2>ZANY|PIXELATED|EUPHORIC|REVERENT|BLOODTHIRSTY|STERN|RECURSIVE|VITUPERATIVE|BRUTALIST|PARANOID|ANGUISHED p_trait>THE STATE|A GOD|A WAR|A SPORT|A MORAL|A VIRTUE|A CONQUEST|A VICTORY|A NATURAL DISASTER epode>NOW, WITH +subtract+ FEWER LINES, AND THESE +ep_style+, IMAGINE HOW +hero+ SHALL +do_to_villain+ +villain+. ep_style>meter2|style1|style2|short_or_long|short_or_long+ AND +meter2|style1+ AND +style2|style2+ AND +meter2 subtract>2|2|2|3|3|3|4|4|5 do_to_villain>OVERCOME|OVERCOME|OVERCOME|REFORM|BANISH|DEMOTE|CENSURE|STEAL FROM|WED|WOUND|BECOME HORATIAN horatian>IN +stanzas+ STANZAS, EACH OF 4 LINES, DESCRIBE +hero+, +gradient+.|IN +stanzas+ STANZAS, EACH OF 4 LINES, DESCRIBE +hero+, +gradient+. +extra+. gradient>PROGRESSING GENTLY FROM+ +concept_statement|PROGRESSING GENTLY FROM+ +concept_statement+ AND SIMULTANEOUSLY FROM +concept_statement2 concept_statement>concept+ TO +concept2 concept>THE +cognizing+ OF THE +abstraction+ OF +object|THE +cognizing2+ OF THE +abstraction2+ OF +object concept2>THE +cognizing2+ OF THE +abstraction+ OF +object|THE +cognizing+ OF THE +abstraction2+ OF +object2 concept_statement2>GREEN TO BLUE|BLUE TO GREEN|WEALTH TO POVERTY|MORNING TO NIGHT|RAIN TO SLEEP|YOUTH TO OLD AGE|FALL TO SPRING|WINTER TO SUMMER abstraction>PAIN|SADNESS|LOSS|HUMOR|FRAILTY|YEARNING abstraction2>LOSS|GROWTH|MERCY|HISTORY|TIMELESSNESS|MORTALITY cognizing>AWARENESS|FORGIVENESS|HATRED|NON-AWARENESS|APPRECIATION|MISUNDERSTANDING|SYMPATHY cognizing2>ACCEPTANCE|PERCEPTION|REGRETTING|UNDERSTANDING object>hero|hero|hero|hero|LIFE IN GENERAL object2>hero|hero|hero|hero|villain|LIFE IN GENERAL stanzas>3|4|4|6|6|8|10 extra>REMARK IN THE +count_line+ LINE UPON +extra_object|prosody extra_object>THE +h_feature+ OF +hero|WINE|WINE|WINE|A MORSEL|A MORSEL|A FRIEND h_feature>FLAVOR|SIZE|TEXTURE|FAMILY|POSITION|TEMPERATURE|ECHO|INTERIOR|FORM|TEMPERAMENT|HONOR|HUE count_line>1ST|rel_num|rel_num+ TO LAST prosody>MIMIC +poet+’S METER poet>SAPPHO|ALCAEUS rel_num>2ND|3RD|4TH BLENDED blended>bl1|bl2|bl3|bl4|bl5|bl6 bl1>[STANZA 1: +pindaric_bit+] [STANZA 2: +pindaric_bit+] [STANZA 3: +horatian_bit+] bl2>[STANZA 1: +pindaric_bit+] [STANZA 2: +horatian_bit+] [STANZA 3: +pindaric_bit+] bl3>[STANZA 1: +horatian_bit+] [STANZA 2: +pindaric_bit+] [STANZA 3: +pindaric_bit+] bl4>[STANZA 1: +pindaric_bit+] [STANZA 2: +horatian_bit+] [STANZA 3: +horatian_bit+] bl5>[STANZA 1: +horatian_bit+] [STANZA 2: +horatian_bit+] [STANZA 3: +pindaric_bit+] bl6>[STANZA 1: +horatian_bit+] [STANZA 2: +pindaric_bit+] [STANZA 3: +horatian_bit+] pindaric_bit>meter1|meter2|short_or_long|style1|style1|style_or_mentioning|strophe|ep_style horatian_bit>gradient|gradient|extra|extra_object|cognizing|cognizing2|concept_statement|concept|concept2|concept_statement2|prosody adj>VINTAGE|COMMON|CIVIC|BROKEN|HONEYED|PAINTED|SACRED|HUNGRY|VERNAL|FLEETING entity>VASE|FRIEND|DOVE|DEER|FRUIT|LAKE|HOUSE|GAME|TUNE|STORM|GLEN|KNOT|VEIL|WRIT

Kavi Duvvoori’s Most Grammatical Grammar

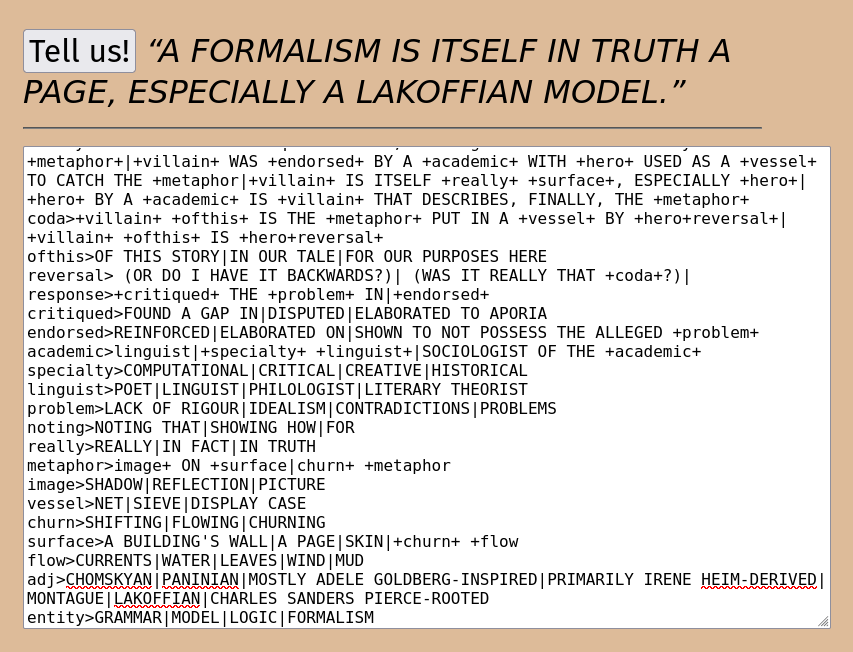

Kavi joined the editorial collective of Taper for this issue (#12) and has really put their shoulder to the wheel! They (like Jhave & Kyle) have been producing serious computer-generated texts and adjacent projects, of course with particular twists. Their grammar uses story elements (hero, villain) and does tell a story — but one about grammars.

story>theory+.|theory+. +coda+. theory>A +academic+ +critiqued+ +hero+, +noting+ +villain+ IS +really+ A +metaphor+|+villain+ WAS +endorsed+ BY A +academic+ WITH +hero+ USED AS A +vessel+ TO CATCH THE +metaphor|+villain+ IS ITSELF +really+ +surface+, ESPECIALLY +hero+|+hero+ BY A +academic+ IS +villain+ THAT DESCRIBES, FINALLY, THE +metaphor+ coda>+villain+ +ofthis+ IS THE +metaphor+ PUT IN A +vessel+ BY +hero+reversal+|+villain+ +ofthis+ IS +hero+reversal+ ofthis>OF THIS STORY|IN OUR TALE|FOR OUR PURPOSES HERE reversal> (OR DO I HAVE IT BACKWARDS?)| (WAS IT REALLY THAT +coda+?)| response>+critiqued+ THE +problem+ IN|+endorsed+ critiqued>FOUND A GAP IN|DISPUTED|ELABORATED TO APORIA endorsed>REINFORCED|ELABORATED ON|SHOWN TO NOT POSSESS THE ALLEGED +problem+ academic>linguist|+specialty+ +linguist+|SOCIOLOGIST OF THE +academic+ specialty>COMPUTATIONAL|CRITICAL|CREATIVE|HISTORICAL linguist>POET|LINGUIST|PHILOLOGIST|LITERARY THEORIST problem>LACK OF RIGOUR|IDEALISM|CONTRADICTIONS|PROBLEMS noting>NOTING THAT|SHOWING HOW|FOR really>REALLY|IN FACT|IN TRUTH metaphor>image+ ON +surface|churn+ +metaphor image>SHADOW|REFLECTION|PICTURE vessel>NET|SIEVE|DISPLAY CASE churn>SHIFTING|FLOWING|CHURNING surface>A BUILDING'S WALL|A PAGE|SKIN|+churn+ +flow flow>CURRENTS|WATER|LEAVES|WIND|MUD adj>CHOMSKYAN|PANINIAN|MOSTLY ADELE GOLDBERG-INSPIRED|PRIMARILY IRENE HEIM-DERIVED|MONTAGUE|LAKOFFIAN|CHARLES SANDERS PIERCE-ROOTED entity>GRAMMAR|MODEL|LOGIC|FORMALISM