Here’s a first effort (drafted, initially, at 2am on July 22) at a bibliography of computer-generated books.

These are books in the standard material sense, somehow printed, whether via print-on-demand or in a print run. I may include chapbooks eventually, as they certainly interest me, but so far I have been focusing on books, however bound, with spines. (Updated June 23, 2017: I added the first chapbooks today.) Books in any language are welcome.

So far I have not included books where the text has been obviously sorted computer (e.g. Auerbach, Reimer) or where a text has been produced repeatedly, obviously by computer (e.g. Chernofsky). Also omitted are computer-generated utilitarian tables, e.g. of logarithms or for artillery firing. Books composed using a formal process, but without using a computer, are not included.

I have included some strange outliers such as books written with computational assistance (programs were used to generate text and the text was human-assembled/edited/written) and one book that is apparently human written but is supposed to read like a computer-generated book.

I’d love to know about more of these. I’m not as interested in the thousands of computer-generated spam books available for purchase, and have not listed any of these, but let me know if there are specific ones that you believe are worthwhile. I would particularly like to know if some of the great NaNoGenMo books I’ve read are available in print.

Updated in 2016 11:43am July 22: Since the original post I have added Whalen, Tranter, Balestrini, and five books by Bök. 5:35pm: I’ve added Thompson and Woetmann. 8:37am July 23: Added Bogost. 8:37pm July 24: Added Bailey, Baudot, Cabell & Huff, Cage x 2, Huff, Hirmes. October 12-14: Added Archangel, Seward, Dörfelt. Updated in 2017 June 12: Added Morris, Pipkin. June 23: Added Clark, Knowles 2011, The Maggot, and four chapbooks: Knowles & Tenney, Parrish, Pipkin (picking figs…), Temkin. September 5: Added Mize. Updated in 2018 September 18: Added the first six Using Electricity books, Montfort, Perez y Perez, Parrish, Zilles, Bhatnagar, Läufer; also, Montfort 2018, King Zog, Goodwin. November 29: Added the three Constant 2013 books. Updated in 2019 February 21: Added Feldman, Giles, Lavigne x 2, Parrish (The Wcnsske…), Waller, Ye. March 5: Added Zolf. September 10: Added Allison, Donnachie, Marche, McConnell, and Soft Ions. September 25: Added Brzeski. October 31: Added Moure, Pentecost, and Reed.

Archangel, Cory. Working on my Novel. New York: Penguin, 2014.

Allison, Karmel and Gregory Chatonsky. Machines Upon Every Flower. Montréal: Anteism Publishing, 2019.

Audry, Sofian. for the sleepers in that quiet earth. Boston and New York: Bad Quarto, 2018.

Bailey, Richard W. Computer Poems. Drummond Island, MI: Potagannissing Press, 1973.

Balestrini, Nanni. Tristano. Translated by Mike Harakis. London and New York: Verso, 2014.

Balousek, Matthew R.F. and Emma Stewart. Exchange of Letters. A Hive of Mechanical Wasps, third installment. Santa Cruz, 2017.

Balousek, Matthew R.F. Gold Chocobo. A Hive of Mechanical Wasps, fourth installment. Mount Vernon, 2018.

Balousek, Matthew R.F. Or, the Whale. A Hive of Mechanical Wasps, second installment. Santa Cruz, 2017.

Balousek, Matthew R.F. Post Meridiem. A Hive of Mechanical Wasps, first installment. Santa Cruz, 2016.

Baudot, Jean. La Machine a écrire mise en marche et programmée par Jean A. Baudot. Montréal: Editions du Jour, 1964.

Bhatnagar, Ranjit. Encomials: Sonnets from Pentametron. Using Electricity series. Counterpath: Denver, 2018.

Bogost, Ian. A Slow Year: Game Poems. Highlands Ranch, CO: Open Texture, [2010].

Bök, Christian. LXUM,LKWC (Oh Time Thy Pyramids). San Francisco: Blurb, 2015.

Bök, Christian. MCV. San Francisco: Blurb, 2015.

Bök, Christian. Axaxaxas Mlo. San Francisco: Blurb, 2015.

Bök, Christian. The Plaster Cramp. San Francisco: Blurb, 2015.

Bök, Christian. The Combed Thunderclap. San Francisco: Blurb, 2015.

Brzeski, Samuel. I laugh while crying. And I barely cry. What’s wrong with me? TEXSTpress, Bergen. 2019

Cabell, Mimi, and Jason Huff. American Psycho. Vienna: Traumavien, 2012.

Cage, John. Anarchy (New York City, January 1988). Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Cage, John. I-IV. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Carpenter, J. R. GENERATION[S] Vienna: Traumawien, 2010.

Cayley, John and Daniel C. Howe, How it Is in Common Tongues. Providence: NLLF, 2012.

Cayley, John. Image Generation. London: Veer Books, 2015.

Chamberlin, Darick. Cigarette Boy: A Mock Machine Mock-Epic. [Seattle]: Rogue Drogue: 1991.

Chan, Paul. Phaedrus Pron. Brooklyn: Badlands Unlimited, 2010.

Clark, Ron. My Buttons Are Blue and Other Love Poems from the Digital Heart of an Electronic Computer. Woodsboro, Maryland: Arcsoft Pub, 1982.

Constant Verlag Brussels. The Death of the Authors: James Joyce & Rabindranath Tagore & Their Return to Life in Four Seasons. Brussels, Belgium. 2013.

Constant Verlag Brussels. The Death of the Authors: Rabindra[na]th Tagore & Virginia Woolf & Their Return to Life in Four Seasons. Brussels, Belgium. 2013.

Constant Verlag Brussels. The Death of the Authors: Sherwood Anderson & Henri Bergson & Their Return to Life in Four Seasons. Brussels, Belgium. 2013.

Daly, Liza. Seraphs: A Procedurally Generated Mysterious Codex. [San Francisco]: Blurb, 2014.

Donnachie, Karen Ann and Andy Simionato. A Nonhuman Reading of Sabri Cetinkunt’s Mechatronics (2006): Part A. The Library of Nonhuman Books, 2019.

Feldman, Shira. the limits of my language are the limits of my world. n.p., n.d.

Friedhoff, Jane. it is a different/friction. 2015.

Fuchs, Martin and Peter Bichsel. Written Images. 2011.

Funkhouser, Christopher. Electro þerdix. Propolis Press. Least Weasel Chapbook Series. 2011.

Giles, Harry Josephine and Martin O’leary. New Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (Dialecty). Book Works, 2018.

Goodwin, Ross. 1 the Road. Jean Boîte Éditions: Paris, 2018.

Hartman, Charles and Hugh Kenner. Sentences. Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Press, 1995.

Heldén, Johannes and Håkan Jonson. Evolution. Stockholm, OEI Editör, 2014.

Hirmes, David. Directions From Unknown Road to Unknown Road. [Handmade edition of 10.] The Elements Press: 2010.

Huff, Jason. Autosummarize. [McNally Jackson]: 2010.

Kennedy, Bill and Darren Wershler-Henry. Apostrophe. Toronto, ECW Press, 2006.

Kennedy, Bill and Darren Wershler. Update. Montréal: Snare, [2010.]

King Zog. Google, Volume 1. Jean Boîte Éditions: Paris, 2013.

Knowles, Alison, James Tenney, and Siemens System 4004. A House of Dust. Köln & New York: Verlag Gebr. König, 1969.

Knowles, Alison. Clear Skies All Week. Onestar Press, 2011.

Larson, Darby. Irritant. New York and Atlanta: Blue Square Press, 2013.

Läufer, Milton. A Noise Such as a Man Might Make. Using Electricity series. Counterpath: Denver, 2018.

Lavigne, Sam. SELF HELP BOOK. New York, NY: Self Published, 2018.

Lavigne, Sam. Taxonomy of Humans According to Twitter. New York, NY: Self Published, 2018.

Maggot, The. Heroic Real Estate Otter of the 21st Century. lulu.com, 2013.

Marche, Stephen. “Twinkle, Twinkle.” Wired. Dec. 2017, pp. 108-115.

McConnell, Gregory Austin. Today is Spaceship Day. n.p., 2019.

Mize, Rando. Machine Ramblings. n.p., 2016.

Montfort, Nick. World Clock. Cambridge: Bad Quarto, 2013.

Montfort, Nick. Zegar ?wiatowy. Translated by Piotr Marecki. Krakow: ha!art, 2014.

Montfort, Nick. #! Denver: Counterpath, 2014.

Montfort, Nick. Megawatt. Cambridge: Bad Quarto, 2014.

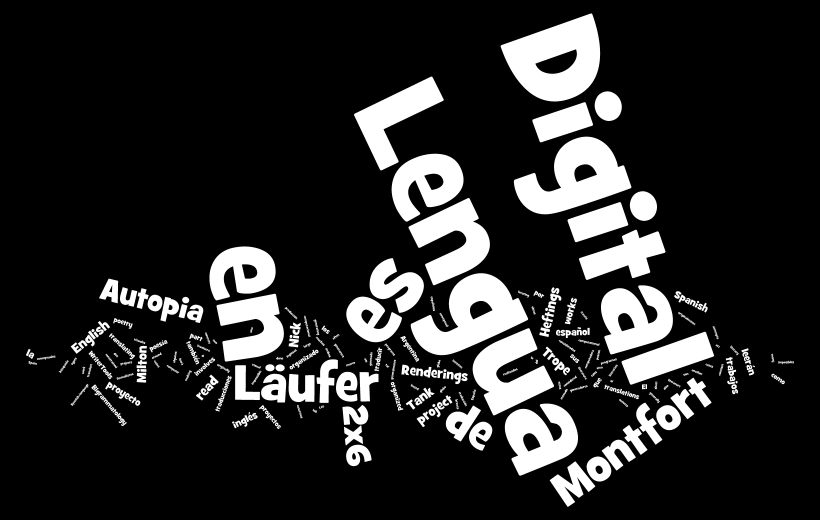

Montfort, Nick, Serge Bouchardon, Carlos León, Natalia Fedorova, Andrew Campana, Aleksandra Malecka, and Piotr Marecki. 2×6. Global Poetics series. Los Angeles: Les Figues, 2016.

Montfort, Nick. The Truelist. Using Electricity series. Counterpath: Denver, 2018.

Montfort, Nick. Hard West Turn. Cambridge: Bad Quarto, 2018.

Moure, Erín. Pillage Laud. Moveable Books, 1999. BookThug, 2011.

Morris, Simon. Re-writing Freud. York, England: Information as Material, 2005.

Parrish, Allison. The Ephemerides. Access Token Secret Press, 2015.

Parrish, Allison. Articulations. Using Electricity series. Counterpath: Denver, 2018.

Parrish, Allison. The Wcnsske-Gonshanshcoma Reconstructions. QUEER.ARCHIVE.WORK, 2018.

Pentecost, Stephen M. Thomas Browne’s Commonplace Book. robineggsky.com, 2016.

Pérez y Pérez, Rafael. Mexica: 20 Years–20 Stories [20 años–20 historias]. Using Electricity series. Counterpath: Denver, 2017.

Pipkin, Katie Rose. picking figs in the garden while my world eats Itself. Austin: Raw Paw Press, 2015.

Pipkin, Katie Rose. no people. Katie Rose Pipkin, 2015.

Racter. “Soft Ions.” Omni. Oct. 1981, pp 96-148.

Racter, The Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed. Illustrations by Joan Hall. Introduction by William Chamberlain. New York: Warner Books, 1984.

Reed, Aaron A. Subcutanean. USA, 2019.

Rosén, Carl-Johan. I Speak Myself Into an Object. Stockholm: Rensvist Förlag, 2013.

Dörfelt, Matthias. I Follow. Series of unique flip-books with computer-generated aspects of animation. Made by the artist. 2013-present.

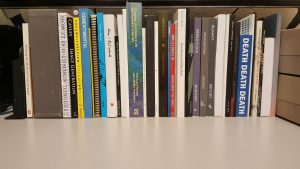

Seward, Rob. Death Death Death. VHS Design LLC, 2010.

Stewart, Emma. My Lovers Learn About the Economy of Debt. n.p., n.d.

Stewart, Emma. Slapping Bandaids on Earthquakes: Thoughts about life under surveillance. n.p., n.d.

Temkin, Daniel. Non-Words. Edition of 100, each with unique words generated by same algorithm used in @nondenotative. n.d.

Thompson, Jeff. Grid Remix: The Fellowship of the Ring. San Francisco: Blurb, 2013.

[Tiar, Louis-Charles]. Let us Now Praise 5,202 Persons. n.p., n.d.

Tranter, John. Different Hands. North Fremantle, Australia: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1998.

Walker, Nathan. Action Score Generator. Manchester: if p then q, 2015.

Waller, Angie. Seeing Like a Computer. New York, NY: Unknown Unknowns, 2018.

Whalen, Zach. An Anthrogram. Fredericksburg, Virginia: 2015.

Woetmann, Peter-Clement. 105 Variationer. Cophenhagen: Arena, 2015.

Ye, Katherine and A. Zhou. Hyperbible. SVN Systems, 2017.

Zilles, Li. Machine, Unlearning. Using Electricity series. Counterpath: Denver, 2018.

Zolf, Rachel. Human Resources. Coach House Books: Toronto, 2007.