Nick Montfort & Páll Thayer

Programs at an Exhibition

At the Boston Cyberarts Gallery

141 Green Street, Jamaica Plain, MA 02130

Located in the Green Street T Station on the Orange Line

Phone number: 617-522-6710

The exhibit runs March 6 through March 16.

Opening: 6pm-9pm, Thursday March 6.

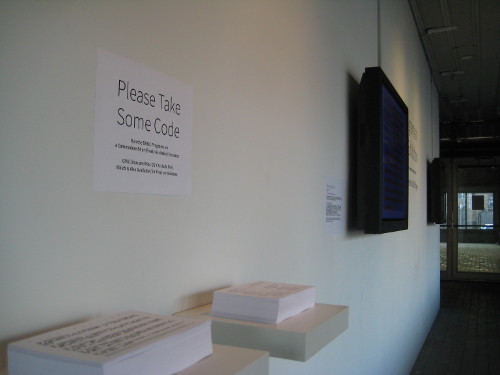

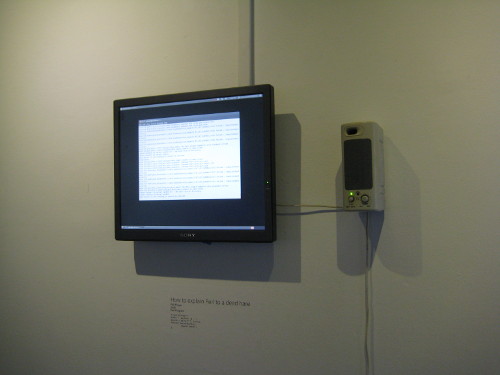

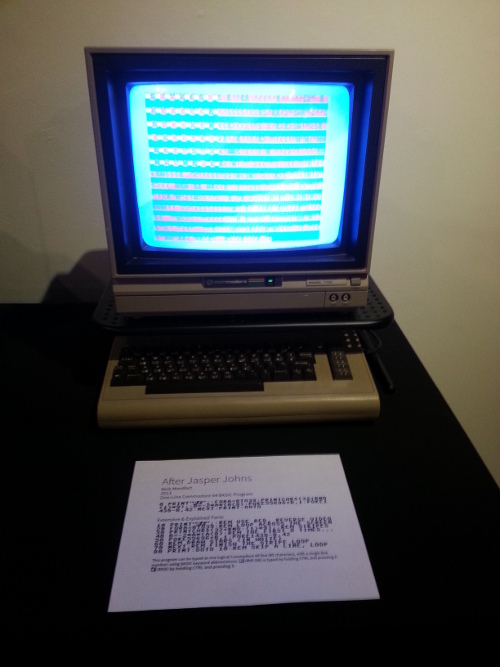

Part of the life of remarkable artworks is that they are appropriated, transformed, and made new. In Programs at an Exhibition, two artists who use code and computation as their medium continue the sort of work others have done by representing visual art as music, by recreating performance pieces in Second Life, and by painting a mustache and goatee on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa. Programs at an Exhibition presents computer programs, written in Perl and Commodore 64 BASIC, each running on its own dedicated computer. The 20th century artworks reenvisioned in these programs include some by painters and visual artists, but also include performances by Joseph Beuys and Vito Acconci. All of the underlying code is made available for gallery visitors to read; they are even welcome to take it home, type it in, and run or rework these programs themselves.

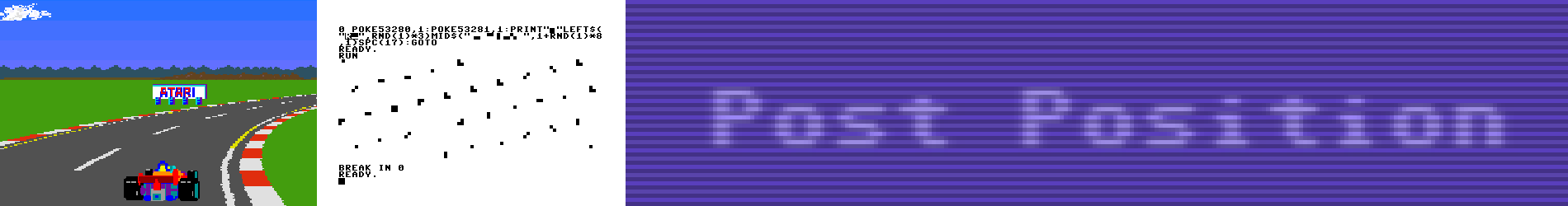

The programs (Commodore 64 BASIC by Nick Montfort, Perl by Páll Thayer) re-create aspects of the concepts and artistic processes that underlie well-known artworks, not just the visual appearance of those works. They participate in popular and “recreational” programming traditions of the sort that people have read about in magazines of the 1970s and 1980s, including Creative Computing. Programmers working in these traditions share code, and they also share an admiration for beautiful output. By celebrating such practices, the exhibit relates to the history of art as well as to the ideals of free software and to the productions of the demoscene. By encouraging gallery visitors to explore programming in the context of contemporary art and the work of specific artists, the exhibit offers a way to make connections between well-known art history and the vibrant, but less widely-known, creative programming practices that have been taken up in recent decades by popular computer users, professional programmers, and artists.

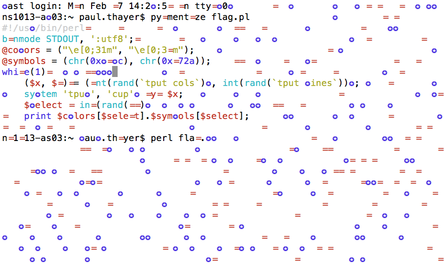

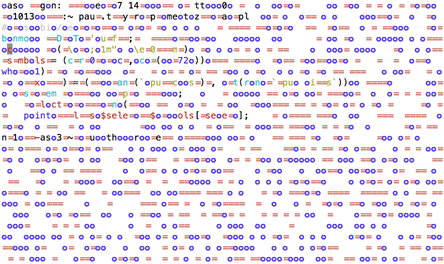

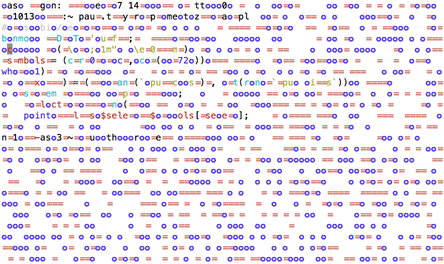

The Perl programs in the exhibit are from Microcodes, a series of very small code-based artworks that Páll Thayer began in 2009. Each one is a fully contained work of art. The conceptual meaning of each piece is revealed through the combination of the title, the code and the results of running them on a computer. Many contemporary programmers view Perl as a “dated” language that saw its heyday in the early ages of the World Wide Web as the primary language used to combine websites with databases. Perl was originally developed by Larry Wall, whose primary interest was to develop a language for parsing text. Because of his background in linguistics, he also wanted the language to have a certain degree of flexibility which has contributed to its motto, “There’s more than one way to do it.” “That motto, ‘TMTOWTDI,’ makes Perl challenging for professional programers who have to take over other’s people code and may struggle to make sense of it,” Thayer said. “But it’s one of the main reasons that Perl, a very expressive programming language, appealed to me in developing this project. This flexibility encouraged Perl programmers to explore individual creative expression in the writing of functional code.”

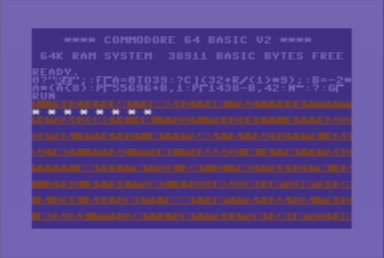

“Páll’s work in Microcodes engages explicitly with the way computer programs are read by people and hwo they have meanings to those trying to understand them, modify them, debug them, and develop them further,” Nick Montfort said. “The Perl programs in Microcodes are quite readerly when compared to my BASIC programs. I’ve tried to engage with a related, but different documented historical tradition — the one-line BASIC program — as it works in a particular computer, the Commodore 64, and to dive into what that particular computer can do using a very limited amount of code, given these many formal, material, and historical specifics. Because my programs are harder to understand, even though they are written in a more populist programming language, I’m including versions of the program that I have rewritten in a clearer form and that include comments.” Montfort’s related projects include a collaborative book, written with nine others in a single voice, that focuses on a particular Commodore 64 BASIC one-liner. The book, published in 2012, is named after the program that is its focus, 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10. Montfort also writes short programs to generate poetry. These include two collections of Perl programs that are constrained in size: his ppg256 series of 256-character programs, and a set of 32-character concrete poetry generators, Concrete Perl. His book #! (pronounced “Shebang”) collects these and other poetry generators, along with their output, and is forthcoming from Counterpath Press.

Nick Montfort develops literary generators and other computational art and poetry, and has participated in dozens of collaborations. He is associate professor of digital media at MIT and faculty advisor for the Electronic Literature Organization, whose Electronic Literature Collection Volume 1 he co-edited. Montfort wrote the book of poems Riddle & Bind and co-wrote 2002: A Palindrome Story with William Gillespie. The MIT Press has published four of Montfort’s collaborative and individually-authored books: The New Media Reader (co-edited with Noah Wardrip-Fruin), Twisty Little Passages, Racing the Beam (co-authored with Ian Bogost), and most recently 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10, a collaboration with Patsy Baudoin, John Bell, Ian Bogost, Jeremy Douglass, Mark C. Marino, Michael Mateas, Casey Reas, Mark Sample, and Noah Vawter that Montfort organized. Nick Montfort’s site, with his digital poems and a link to a free PDF of 10 PRINT: http://nickm.com

Páll Thayer is an Icelandic/American artist working primarily with computers and the Internet. He is a devout follower of open-source culture. His work is developed using open-source tools and source code for his projects is released under a GPL license. His work has been exhibited at galleries and festivals around the world with solo shows in Iceland, Sweden, and New York and notable group shows in the US, Canada, Finland, Germany, and Brazil. Páll Thayer has an MFA degree in visual arts from Concordia University in Montréal. He is an active member of Lorna, Iceland’s only organization devoted to electronic arts. He is also an alumni member of The Institute for Everyday Life, Concordia/Hexagram, Montréal. Páll Thayer currently works as a lecturer and technical support specialist at SUNY Purchase College, New York. Páll Thayer’s Microcodes site: http://pallthayer.dyndns.org/microcodes/

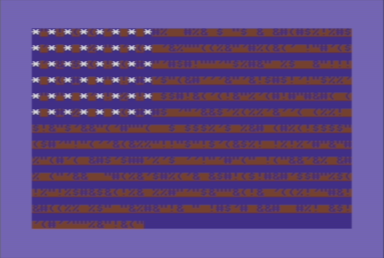

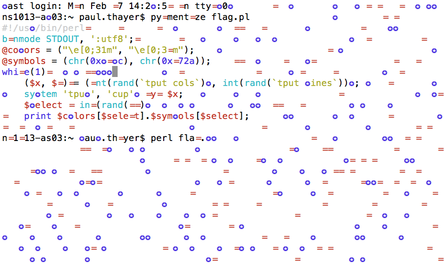

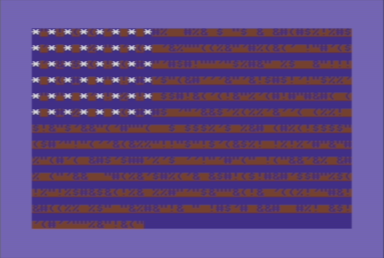

Ten programs will be exhibited, running on ten computers. Two of them, one in Perl by Páll Thayer and one in Commodore 64 BASIC by Nick Montfort, are based on the same artwork, Jasper Johns’s Flag:

Flag · Páll Thayer

Perl program · 2009

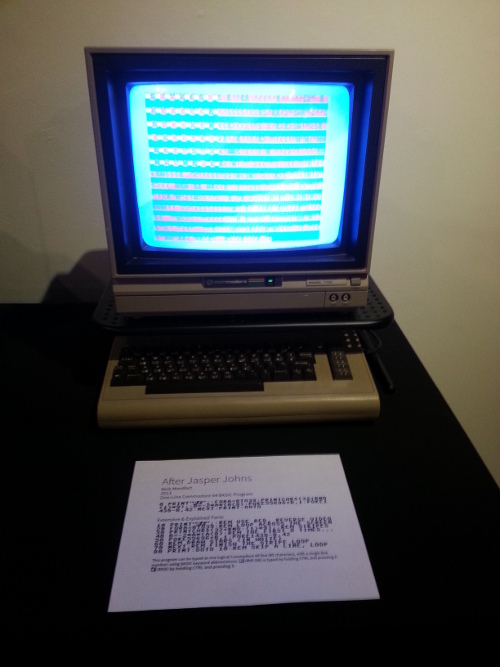

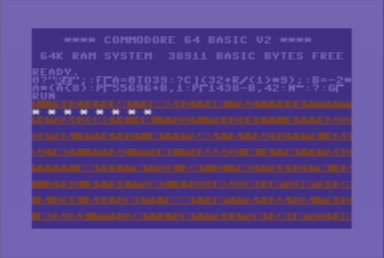

After Jasper Johns · Nick Montfort

one-line Commodore 64 BASIC program · 2013