Yes, It’s a Nonsense Word

The lowdown on Zork‘s name, inasmuch as a lowdown has been provided in print, was given by authors Dave Lebling, Marc Blank, and Tim Anderson in 1979 in the article “Zork: A Computerized Fantasy Simulation Game,” Computer 12:4, 51-59 (April 1979):

The first version of Zork appeared in June 1977. Interestingly enough, it was never “announced” or “installed” for use, and the name was chosen because it was a widely used nonsense word, like “foobar.”

This is a clear explanation, but it raises the question of how this particular nonsense word came into wide use at MIT. It seems reasonable to pursue this question, and reasonable that there would be some discernable answer. After all, there’s a whole official document, RFC 3092, explaining the etymology of “foobar.” It could be interesting to know what sort of nonsense word “zork” is, since it’s quite a different thing, with very different resonances, to borrow a “nonsense” term from Edward Lear or Lewis Carroll as opposed to Hugo Ball or Tristan Tzara. “Zork,” of course, doesn’t seem to derive from either humorous English nonsense poetry or Dada; the possibilities for its origins are more complex.

Slouching from “Zorch”?

In the first part of “The History of Zork,” The New Zork Times 4:1 (Winter 1985), Tim Anderson adds to the earlier discussion and suggests a possible derivation for the word:

Zork, by the way, was never really named. “Zork” was a nonsense word floating around; it was usually a verb, as in “zork the fweep,” and may have been derived from “zorch.” (“Zorch” is another nonsense word implying total destruction.) We tended to name our programs with the word “zork” until they were ready to be installed on the system.

“Zorch” is listed in Peter R. Samson’s 1959 “TMRC Dictionary” – the dictionary of the Tech Model Railroad Club, an organization that was important in helping to begin and foster recreational computing. The term meant, at that time, “to attack with an inverse heat sink” – that is, to attack with a heat source – and is explained as “Another of David Sawyer’s sound effects, which I reinterpreted as a colorful variant of ‘scorch.'” It could also be imagined as a variant of “torch” – either way, the application of heat is suggested. This definition is consistent with the sense of “zorch” that Anderson gives, although a bit more specific. It is quite possible that “zork” does derive from “zorch,” as Anderson and others guess, but it is not clear why a word so derived would then be used as a placeholder program name. It’s also at least arguable that “zork” sounds less destructive than “zorch,” as the unintimidating back-formations “scork” and “tork” suggest. If that’s the case, why would a less intense term come to be used when the original term is more intense and very comical? While the “zorch” etymology might be right, it at least seems worthwhile to look to other possibilities.

Textbook Examples

“Zork” occurs occasionally, although rarely, as a proper name in various print sources in the decades leading up to 1977. Google Book Search reveals that some more nonsensical uses occur in some textbook examples in the 1970s. In Introduction to Experimental Psychology by Douglas W. Matheson, Richard Loren Bruce, and Kenneth L. Beauchamp (1970, 2nd. ed 1974) the meaningless “zork” model is introduced as a contrast to a medical model. “Zork” is also used as a fictional place name in Henry F. DeFrancesco’s 1975 Quantitative Analysis Methods for Substantive Analysts. There is some chance that the term was picked up from such a source. Zork explicitly pokes fun at the material nature of textbooks by including a “this space intentionally left blank” joke, which refers to a message sometimes printed on textbook’s blank pages to let readers know that they have not been left blank due to a printing error. Given this, it would be hard to rule out to possibility of the term “zork” coming from a textbook. Of course, the term could have appeared at MIT indirectly, in an example given in a lecture, on a problem set, or on a test, even if a book with the example in it was not assigned as a text. But there is nothing to strongly recommend this etymology, either. And while the former textbook example is clearly the more vivid, it is also much less likely to have been encountered by the Zork authors, [updated January 10] since they were involved with a computer science research group, Dynamic Modeling. MIT does not now have a department named psychology, but Course 9 (now Brain and Cognitive Sciences) was called Psychology from 1960-1985.

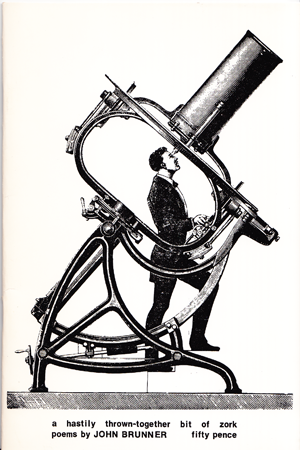

There has been some speculation – specifically, in this mailing-list thread – that the term “zork” may come to MIT via John Brunner, whose poetry chapbook A Hastily Thrown-Together Bit of Zork was published in 1974. Although the sense of the word as it appears in the title is completely consistent with the MIT meaning of the term, it is not clear that this 24-page pamphlet, published by Square House Books in an edition of 200 (50 numbered and signed), had made it to MIT by the time Zork coalesced, beginning in 1977. Nevertheless, the idea of a science-fictional vector for the term is appealing.

How Brunner Happened upon “Zork”

On the unnumbered second page of A Hastily Thrown-Together Bit of Zork, Brunner notes that “the title resulted from Simon Joukes’s first encounter with a typewriter that didn’t speak Flemish.” According to this history of Dutch and Flemish fandom, Simon Joukes was active in Flemish fandom and was a part of the club Sfan, helping to publish Info-Sfan, which became SF Magazine.

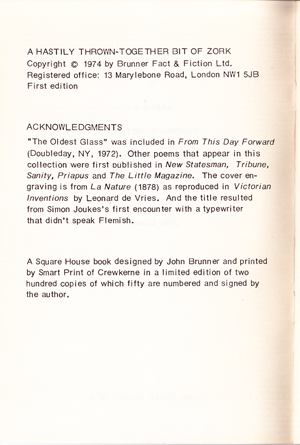

Here is a Belgian typewriter, manufactured by Olivetti. (This blog post is the source for the image.) The letters are laid out just as they are on a French typewriter, in the AZERTY scheme. As you can see, if you’ve learned to type the word “WORK” on a typewriter like this, and someone then substitutes a British (or US) typewriter without your noticing, and you then try to type that word without looking at the keys, you’ll type “ZORK.” (Since the “W” and “Z” are switched in this layout, the same thing would happen to a British typist who uses to a Belgian typewriter without noticing how the keys are labeled.)

It’s particularly appealing that this etymology makes zork an altered form of, or an alternative to … work.

Another Science-Fiction “Zork”

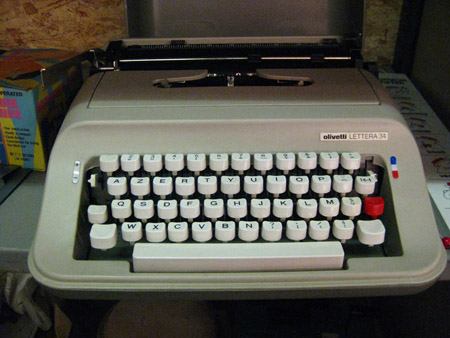

Brunner’s use of “zork” in the title of his book was not the first appearance of the word in science fiction. The word made an appearance earlier in Lin Carter’s novel The Purloined Planet, published in 1969. It was used in the name of an important character … “Zork Arrgh.”

It’s likely that Brunner at least glanced at the name of this key character. Lin Carter’s novel was published in a Belmont Double edition with “two complete science fiction novels.” The other was Brunner’s The Evil That Men Do.

While Simon Joukes may have typed out the word “Zork” and directly inspired Brunner’s 1974 title, the word may have rang out to Brunner as interesting and particulaly amusing because of Carter’s earlier use of it.

“Zork” and How She Is Spoke

There is some chance that people at MIT saw Brunner’s slim book of poems, but it seems far from certain. As of this writing, WorldCat lists only four university libraries in the United States that have this limited-edition book. MITSFS, the MIT Science Fiction Society, boasts the world’s largest open-stack library of science fiction and has 83 titles by Brunner in its catalog – but A Hastily Thrown-Together Bit of Zork is not among these. The Evil That Men Do / The Purloined Planet is in the collection, however.

Even when all of these additional leads are considered, it seems there is no strong conclusion to be drawn about the deeper etymology of the name of MIT’s, and Infocom’s, most famous text adventure. “Zork” might have been a corruption or further development of “zorch.” It may have entered the argot because of its use in an amusing curricular example, perhaps thanks to Quantitative Analysis Methods for Substantive Analysts or another textbook that hasn’t yet been ingested into Google Books. Or, science fiction may have been the vector for the word. If it was, though, it seems likely that it made its way into MIT speech not because of Brunner’s book of poems, but thanks to Zork Arrgh, a key character in 1969 novel by Lin Carter, one that was sitting on the shelves at MITSFS.

Perhaps more evidence will come to light, and the origins of the word “zork” as it was used at MIT in the late 1970s will become clear. Or, it may be that the origins of the word are lost forever – obliterated in a nook of a subculture’s linguistic history that has been irreversibly zorched.