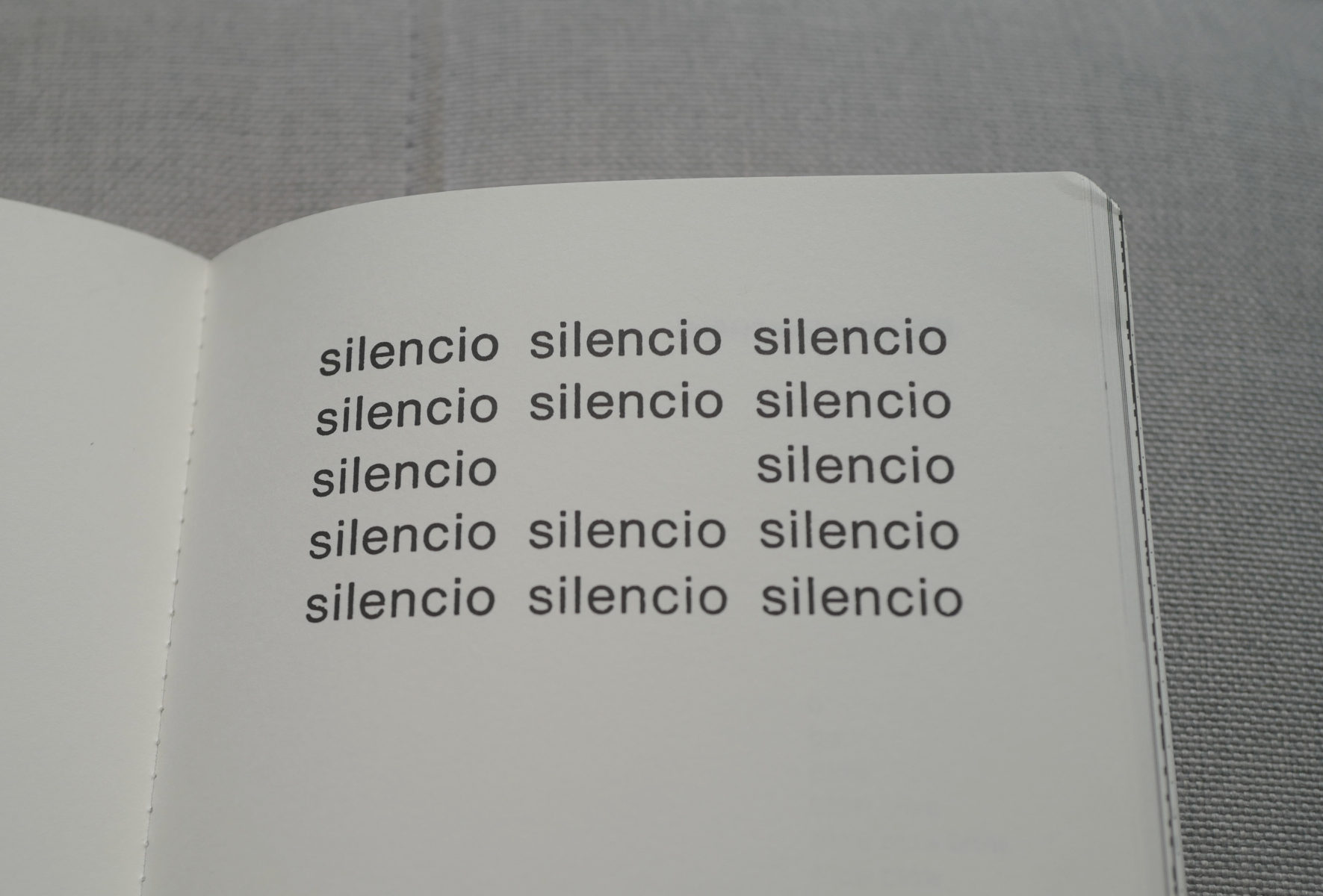

The untitled poem by Eugen Gomringer that we can only call “silencio” is a classic, perhaps the classic, concrete poem. According to Marjorie Perloff’s Unoriginal Genius, the “silencio” version of the poem dates from 1953. In my 1968 edition of The Book of Hours and Constellations I find the German manifestation of this poem (with the word “schweigen”) and the English poem (with the word “silence”), on the same page at the very beginning of the book — but no “silencio.” The place where I do find “silencio” is An Anthology of Concrete Poetry from 1967, edited by Emmett Williams. My copy is the re-issue by Primary Information.

Williams mentions tendencies and tries not to too strongly characterize any particular poets in the anthologies when he writes, in the introduction:

The visual element of their poetry [the concrete poets’ poetry] tended to be structural, a consequence of the poem, a “picture” of the lines of force of the work itself, and not merely textural. It was poetry beyond paraphrase … the word, not words, words, words or expressionistic squiggles …

There are several essential points here about the project of concrete poetry and how it differs from, for instance, the shapes of “Easter Wings” and the other poems in George Herbert’s The Altar, as well as the way Lewis Carroll presented the image of a mouse’s tail in words that tell the mouse’s tale in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. However brilliant these two writers were, in these cases they were using language to make pictures; the concrete poets, beginning with Gomringer, worked to create structures. Their poems are not just verse (lineated language), but made from lines of force. In many cases, as with the unnamed poem I must call “silencio,” an entire concrete poem can be understood to cohere as a word.

There are other interpretations of Gomringer’s poem that situate it in history, but I will give a simple one that situates it within the project of concrete poetry — followed by another that places it in a different and much longer-lived poetic tradition.

The lines of force of this poem are, most obviously, those that allow for the gap in the middle where the ground (the absence of text, the absence of “silencio”) becomes figure. As ink declares silence, or, if we read the text aloud, as our voice declares silence, attentive readers can’t help but notice a truer silence in the middle of the page.

At the next stage, there is silence between each “silencio,” horizontally and vertically. We overlook this gap, which is seen even when text is not presented on a grid. It too will be represented if we read the poem aloud, however, between each spoken word.

We can go further, although ear and eye would not agree about the silences. There are spaces, and thus silences of a visual sort, between each of the letters in “silencio,” too.

Fascinating, isn’t it, that John Cage’s 4’33” was composed and presented in 1952, preceding this poem? This poem, too, seems to structurally show, through its lines of force, that silence can take center stage.

In any case, without offering more than a brief appreciation, I mean to make it clear that this is a quintessential concrete poem. One can read it out loud, but that does not provide the listener with the effect of apprehending the structure of the poem on the page. The poem is not a picture of anything. It is a structure. And it is not squiggles or simply a bunch of words, even if the single lexeme “silencio” is repeated fourteen times. It is fitting to apprehend and read the whole poem as a word, not a bunch of words.

Accepting this, I would like to offer an interpretation of this poem that may seem perverse, but which I believe shows this poem’s radical versatility: It can be seen in the light of a poetic tradition that long predates concrete poetry. This poem is not only a concrete poem, but also a sonnet. Specifically, I’ll argue that although the repeated word is a Spanish word, it fits into the English-language tradition of the sonnet. Because concrete poetry is a transnational phenomenon and Gomringer writes in English as well as German and Spanish, this disjunction may be less unusual that it otherwise would be.

Consider that the poem consists of fourteen occurrences of “silencio,” which despite their unusual arrangement on the page can be read aloud as fourteen lines. It would be hard not to read them this way.

Because each word is the same, the poem follows the rhyme scheme of a sonnet — any rhyme scheme, including the Petrarchan or Shakespearean in English, including those typical in Spanish.

If some reader finds it impossible for the same line to be repeated fourteen times in a sonnet, I refer this reader to the 2002 “Sonnet” by Terrance Hayes, which consists of fourteen repetitions of the line “We sliced the watermelon into smiles.”

But is it metrical? The word “silencio” pronounced by itself has two metrical feet ( x / | x / ) and is in perfectly regular iambic dimeter. This is also the meter of Elizabeth Bishop’s last poem, “Sonnet,” which begins:

Caught — the bubble

in the spirit level,

a creature divided;

and the compass needle

There’s much more variation in Bishop’s poem, but the metrical regularity of Gomringer’s poem shouldn’t preclude it from being in this particular form. While I don’t have an example of a sonnet with repeated lines (like the one by Hayes) from before 1953, there are earlier sonnets in dimeter, or one, at least: a piece of light verse by Arthur Guiterman, published in The New Yorker on July 7, 1939.

Sonnets can be about anything, although the form does have a heritage. Reading the poem as a sonnet allows us to make a connection to the sonnet tradition if we wish. We can, for instance, ask whether this sonnet has anything to do with love, whether in the most traditional sense of love for a woman or, in John Donne and Herbert’s senses, religious love. Could the silence of this sonnet be that of being understood, and of not needing to say anything aloud?

Seeing this Gomringer poem as a sonnet also allows us to put it into conversation with other one-word texts (those that have several tokens but repeat a single type) that can also be viewed as sonnets, because they have fourteen tokens.

The one I know of, and which fascinates me, is Dance, a typing by Christoper Knowles that I saw contextualized as visual art in his 2015 solo show at the Philadelphia ICA. The page of this work is blank except for a line at the top that repeats the word “DANCE” (in capital letters) fourteen times, with a space between each occurrence. This makes for 83 characters: 5 × 14 = 70 for the word DANCE, plus the 13 spaces that go between each pair of words. While a sheet of paper is typically thought to accommodate 80 typewritten characters across its width, Knowles found that by beginning at the extreme left edge of the page and typing to the extreme right edge, he could fit exactly 83 onto it.

The typing Dance can be read as a sonnet in hemimeter — a term used by George Starbuck for “half-feet,” and associated with light verse. Where “silencio” offers a more static and contemplative structure, I can’t help but imagine Knowles typing DANCE repeatedly, his hands dancing on the typewriter, as he also produced a text that is a score, instructing us to dance. Not so much a structure, it seems to me, but an exhortation and a trace of its making. And, of course, a text that can be read in the sonnet tradition, asking us to consider how dance, repeated, insistent, filling the width of the page completely, relates to love.