Thanks to Neural.it, the very long-running, vigorously-firing Italian site and magazine on digital media art and related topics. This publication did a writeup of my and Stephanie Strickland’s poetic system Sea and Spar Between. It’s available in English and in Italian.

Conferencing on Code and Games

First, as of this writing: I’m at the GAMBIT Summer Summit here at MIT, which runs today and is being streamed live. Do check it out if video game research interests you.

A few days ago, I was at the Foundations of Digital Games conference in Bordeaux. On July 1 I presented the first conference paper on Curveship since the system has been released as free software. The paper is “Curveship’s Automatic Narrative Style,” which sums up or at least mentions many of the research results while documenting the practicalities of the system and using the current terminology of the release version.

Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Malcolm Ryan, Michael Young (next year’s FDG local organizer) and Michael Mateas in between sessions at FDG 2011.

At FDG, there was a very intriguing interest in focalization, seen in Jichen Zhu’s presentation of the paper by Jichen Zhu, Santiago Ontañón and Brad Lewter, “Representing Game Characters’ Inner Worlds through Narrative Perspectives” and in the poster “Toward a Computational Model of Focalization” by Byung-Chull Bae, Yun-Gyung Cheong, and R. Michael Young. (Zhu’s work continues aspects of her dissertation project, of which I was a supervisor, so I was particularly interested to see how her work has been progressing.) Curveship has the ability to change focalization and to narrate (textually) from the perspective of different characters, based on their knowledge and perceptions; this is one of several ways in which it can vary the narrating. I’ll be interested to see how others continue to explore this aspect of narrative.

Before FDG was Digital Humanities 2011 at Stanford, where I was very pleased, on June 22, to join a panel assembled by Rita Raley. I briefly discussed data-driven poetic practices of different sorts (N+7, diastic writing, and many other forms) and presented ppg256 and Concrete Perl, which are not data-driven. I argued that as humanists we should be “digging into code” as well as data, understanding process in the new ways that we can. It was great to join Sandy Baldwin, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, and John Cayley on this panel, to discuss code and poetry with them, and to hear their presentations.

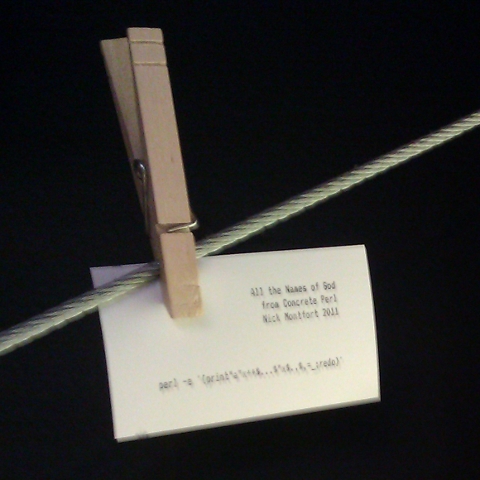

Concrete Perl

h d d k x v d r k y p s b a b a n i k d u u

v r c q i e z j s s v h t l i r k k n k n n m

z b q b k x m d u z f s g p u z v y v m f s

i u p p z r n t k f b h v q l x w h x f x c i w v f

k h l a i o q s z n z u n c l w d a d a m j b e

m n b q o u o e n s r b o j b q q t q s f n i f u l

Concrete Perl

a set of four concrete poems realized as 32-character

Perl programs

by Nick Montfort

– All the Names of God

– Alphabet Expanding

– ASCII Hegemony

– Letterformed Terrain

You can download the linked Perl files and/or simply copy and paste the following four lines, which correspond to the four titles above:

– perl -e '{print"a"x++$...$"x$.,$,=_;redo}'

– perl -e '{print$,=$"x($.+=.01),a..z;redo}'

– perl -e '{print" ".chr for 32..126;redo}'

– perl -e '{print$",$_=(a..z)[rand$=];redo}'

For purposes of determining the platform precisely and counting characters, the rules of Perl Golf are

used. These rules, for instance, do not count the (optional) newline at the end of a one-line program. The Concrete Perl programs work on all standard versions of Perl 5.8.0 and have been verified as 32 characters long using a count program.

These programs are also written to work and to be visually pleasing on terminal windows (or terminals) of any geometry.

To present them all at once, you can tile four windows and run one program in each window. For instance, running Linux with Compiz as the window manager and the Grid plugin installed and active, create four windows and assign them to the four corners of the screen using Ctrl-Alt-Num Pad 7, Ctrl-Alt-Num Pad 9, Ctrl-Alt-Num Pad 1, and Ctrl-Alt-Num Pad 3. In this

mode if the resolution of the display is not particularly high, you may wish to decrease the font size a notch in each window.

Concrete Perl was released onto the demoscene and discussed by me for the first time in my talk “Beyond Data-Driven Poetry: ppg256 and Concrete Perl,” on the panel “Literary Practice and the Digital Humanities, Redux: Data as/and Poetry,” Digital Humanities 2011, Stanford, June 22, 2011.

I have printed the four programs/poems on a dot matrix printer on business cards and am handing them out and, in some cases, adding them to the “Interactive Poetry Wall” at Stanford University’s “Coho” coffeehouse.

p j o c v v n v t g k t i s h f j v e d v c e b

p z p e s s d o f z v p s t z i b f j w l

p z y f j w k k p k y n v f g u m r m k x i w l s a t n b a f

w q y u t p r p w p m d x j c j j n z k a j z i s

w a w q k j y y k c r d i b p f z h i x i

c o x f p f u d g z y f b y v q v g v o j l

XO and GUI Found in Curveship’s Alphabet Soup

I went by to OLPC (One Laptop Per Child, the nonprofit that has created and deployed worldwide the green laptop for kids) yesterday for some discussion of narrative interfaces. I explained the basics of Curveship and what was interesting about it from my perspective, mentioning that one could hook the narrating engine up to something other than an interactive fiction world. I also found out that others had some of their own, very interesting, ideas.

Chris Ball, for instance, showed a proof-of-concept where he hooked up the simulated world of Curveship’s Cloak of Darkness, the classic simulated example world, to a graphical display and a graphical system for inputting commands:

Source is available on github. While it doesn’t generalize to every Curveship game, what it presents on the screen here is done without any additional game data: Chris’s system determine that the south room is dark and obscures it, determines where the exits are, places objects in rooms, and generates rooms of random size since there is no way to determine how big or small a room is. The only thing the systems knows about the underlying simulated world is what’s in fiction/cloak.py, the file I put together to demonstrate Cloak of Darkness in the usual textual interface.

On the one hand, it more or less discards all of the work that fascinates me the most, the text generation and narrative variation part of the system (*). But on the other, it’s the most radical narrative variation yet – replacing the textual interface with a graphical one. A pretty neat twist on the system, and one which is very interesting from a research standpoint if one’s interested in comparing image and text in narratives.

I hope work on this will continue and that we’ll find other mutually beneficial ways to connect Curveship with the OLPC project.

(*) It doesn’t really discard these or truly “replace” the text channel. You also get to read the textual description of rooms and the textual representation of actions in windows as you play the game. But it makes the main interface a GUI rather than a textual exchange.

World’s Hottest Platforms 2011

Ian Bogost and I were thinking about the Platform Studies series today, as we are wont to do. There are two books in the series that are nearing completion now, which we are delighted about, but there are many more to be written. We were talking about some platforms that we thought were large and low-hanging fruit for any interested authors – ones that would be great to write about. These are a few platforms or families of platforms that seem to us to have interesting technical aspects, diverse and important historical connections, a good amount of worthwhile cultural production, and a number of adherents:

– Apple II

– BASIC

– Commodore 64

– Flash

– Game Boy and/or Game Boy Advance

– iPhone and iPad

– Java

– Macintosh

– MSX

– NES

– PC

– System/360

– Unix and Linux

– Windows (“Wintel”)

In case there’s anything that seems puzzling about this list: A platform, as far as the Platform Studies series is concerned, is something that supports programming and programs, the creation and execution of computational media. (This is pretty much what Wikipedia defines as a computing platform, too.) So BASIC, Java, and Flash are as much platforms as the mainly-hardware consoles and computers that are listed, as are the operating systems on the list.

If any of these interest you enough that you’d consider writing a book about them, please contact me and/or Ian. If you have a favorite platform that we haven’t mentioned and want to suggest that someone write about it, please leave us (and any potential authors who are reading) a comment.

A New Game Studies Brings Racing Reviews

A new issue of Game Studies, the pioneering open-access journal that deals with computer and video games, is out. Of particular note – to me, at least – is that among this issues eight book reviews are two reviews of the book I wrote with Ian Bogost, Racing the Beam.

The two reviews are “Hackers, History, and Game Design: What Racing the Beam Is Not” by José P. Zagal and “The fun is back!” by Lars Konzack.

Zagal, who has a very interesting take on our project, calls the book “an accessible nostalgia-free in-depth examination of a broadly recognized and fondly remembered icon of the videogame revolution” and notes that it is “a book that both retro-videogame enthusiasts and scholars should have on their bookshelves.”

It’s important to note that Konzack developed a layered model for how games (and other digital media artifacts) can be abstracted and situated within culture in his article “Computer game criticism: A method for computer game analysis.” With only a few alterations (merging the “software” and “hardware” layer together into a “platform” layer, for instance, and considering the cultural context as influencing all layers), this model is used in Racing the Beam and in the Platform Studies book series. Konzack finds the book “a worthwhile read if the reader wants to know how early videogame development took place and thereby get an understanding of how videogame development came into being what it is today.”

I’m very pleased, as Ian is, to read these critics’ resposes to our book.

Generador de la Historia “The Two” en Español

Thanks to Carlos León, there is now a Spanish version, “Los Dos,” of my simple but (I think) provocative story generator “The Two.” The system was previously translated into French as “Les Deux” by Serge Bouchardon.

Stop by and check them out; all three are available in JavaScript versions that run right away in a browser. For those who are interested, the original Klingon, er, Python, is also available for each of the three languages.

The reader who takes the time to try to actually understand the output and resolve the pronouns in it will see that often this task is complicated by ambiguity in gender, although syntax and power relations also work to suggest certain ways that pronouns can be resolved. The need to leave the gender of the characters indeterminate in the first line posed particular problems, and slightly different problems, for the French and Spanish translators, who each found a solution.

The Digital Rear-View Mirror

I’m at the intriguing and very sucessful third 2011 symposium of TILTS, the Texas Institute for Literary and Textual Studies. (Interestingly, TILTS can be spelled using only letter from “The X-Files.”) I might have written more about the event, but my computer has been identified by automated UT-Austin systems as being a rooted Windows machine (although it’s not a Windows machine at all) and is banned from the network. Desite my radio silence, though, the symposium has certainly been a space of lively discussion of digital media work, computational linguistics and its application to humanistic inquiry, and the representation of technology in media.

I’ll mention a bit about the talk I gave today, one entitled “The Digital Rear-View Mirror.” The title was based on the dictum of Marshall McLuhan: “We see the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backwards into the future.” The most obvious version of the digital rear-view mirror is the one on your Prius, but I started my comments about three specific topics (and one lament) by examining the nature of emulators, a type of rear-view mirror that’s been of great use to me.

I considered how emulators can be understood, via textual studies, as editions of computers, and how this helps us to better conceptualize the emulator and make more effective use of it in our work. This is a topic I wrote about recently here on Pole Position.

Then, I quickly introduced my current book project, which often involves emulators and is entitled “10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1);: GOTO 10”. I am writing a single-voice academic book with nine other authors; the book is about the one-line Commodore 64 BASIC program that is its title.

For the last of my three specific topics, I took my recent collaboration with Stephanie Strickland, Sea and Spar Between, a literary and aesthetic project which was based in part on consideration of the lexicon of Dickinson’s poems and of Moby Dick.

I wound up with some discussion of how the mainstream definition of the digital humanities, as effectively provided by funding agencies, does not clearly admit any of my specifics (building or using emulators, writing a book with nine others about a short program, collaborating on a poetry generator). None of these projects involve digitization or computational analysis of cultural heritage materials. Perhaps Sea and Spar Between, which involves computing on language but is not even a scholarly project, is actually closest to being a digital humanities project, but it isn’t that close.

Although people like our keynote speaker Johanna Drucker, Matt Kirschenbaum (who spoke on the panel with me), and Lev Manovich have done extremely significant work with contemporary objects of study and are also significant figures within the digital humanities, the exclusive fixation on the past means that we do not have major digital humanities projects about contemporary computational work – electronic literature, video games, computer music, digital installation art, etc.

So, I concluded with a plea to let there be some intersection between “digital media” and “the digital humanities” – to allow us a side-view mirror that would let us see what is happening alongside us, and in the recent past, as well.

The X-Files

[This is a review of, or summary of, or comment on on The X-Files – the complete, nine-season television series and the two movies – written under constraint.]

The title files, the X-Files, exist. His fief.

His silliest, fishiest thesis: Lithe, sexless elitist “eels” exist. These sliest eels flit. These eels felt his sis. Eels flee. Exit sis. She left: Exile.

She, steel theist, feels little. Little else lifts life.

His fetish: Elfish feet? He, slitless, sexless, sees little fetishist sex, feels less.

She sifts the lifeless: filth, shit. She lifts the sheet: The stiff. She sees his teeth, hefts his testis. The fifth stiff, the sixth stiff…

The telex testifies: Hellish flesh seethes, flies flit.

He hits the shiftiest sexist, fells his stilts. The sexist flees — the shit.

She, fleet, heelless, hits the feistiest, flexile thief.

Effete esthetes teethe filets.

His ties stifle.

She flexes; helix lilts.

He flees; she flees.

Hell itself seethes.

Islets: Sessile shellfish sit.

He tilts. He hexes, his hex hits. She feels his hilt. He feels titties. Sex! … Sex?

Charles Bernstein Sounds Off

Charles Bernstein just gave the keynote-like presentation at E-Poetry. (Actually, he used PowerPoint.) I’m providing a few notes, feebly extending in my subjective way some of his oral and photographic/digital presentation for those of you in the information super-blogosphere.

He started by mentioning the UB Poetics Program and its engagement with digital humanities, saying: “As Digital Humanities departs from poetics, it loses its ability to articulate what it needs to articulate.”

EPC and PennSound, he explained, are noncommerical spaces that aren’t proprietary, don’t have advertising, and are not hosted on corporate blogs or systems. These are dealing with digital archival issues – not as much computational poetry – but very important work to do on the Web. There was no foundation support for EPC, even though it was acknowledged as the most widely used poetry site on the Web.

PennSound, a project with the strong support of Penn thanks to the work of Al Filreis, has around 10 million downloads/year – even bigger than Billy Collins! There are about 40,000 individual files. This is bigger than anyone thinks poetry is today. But the NEH won’t fund the project because we aren’t mainly a preservation project; we don’t put audio on gold-plated CDs and place them in a vault.

Bernstein’s new book _Attack of the Difficult Poems_ gives an account of language reproduction technologies and poetics, explaining how different technologies exist overlaid at once. Hence, he explained that he is interested not only in e-poetry but also in d-poetry and f-poetry. Alphabetic, oral, and electronic cultures are overlaid today.

Talking machines, since Edison’s recitation of “Mary had a little lamb,” produce sounds that we process as if they were speech. The recorded voice only speaks and is private – unlike in the public of a live talk. The digital creates proliferations of versions, undermining the idea of the stable text even further.

Bernstein demonstrated the aesthetics of microphone breakdown and then explored the poetic possibilities of the presenter having difficulties with computer interface – he played some audio clips, too, showing that the “archives” we are discussing are productive of new works. Bernstein also welcomed an outpouring of “cover versions” of poems. Poets now only read each others’ work aloud at memorial gatherings. “Any performance of a poem is an exemplary interpretation.” Bernstein went though the specifics of four possibilities found in speech but not in text. Bernstein discussed “the artifice of accent” and how recorded voice, and digital access, have been important to this aspect of poetry.

Bernstein went on to discuss Woody Allen’s fear of books on tape, odd for someone for whom the more recent technologies of TV were so important. Charles presented his Yeats impersonation, which he suggests may be not as important as Yeats’ actual recorded reading, just as the Pope’s prayers may actually be more important even though we like to think that everyone’s are the same. Sound writing is the only kind of writing other than unsound writing.

I have a final image macro based on something Bernstein said immediately before he corrected himself. I hope this gives you some idea of why I’m a follower, a close follower, of Charles Bernstein…

Some Notes on E-Poetry

[If this is funny to anyone, it will probably be funny to people here at E-Poetry. Nevertheless, I offer it up here to the Internet as a curious digital relic of this gathering.]

An Alphabet in 25 Characters

I’m here at the University at Buffalo enjoying the E-Poetry Festival. Amid this discussion of digital work, concrete poetry, and related innovative practices, and among this great crowd of poets, I’ve developed a very short piece for anyone with Perl installed to enjoy – just copy and paste on the command line:

yes | perl -pe '$.%=26;$_=$"x$..chr 97+$.'

It does use “yes,” one of my favorite Unix/GNU commands, and the -p option to wrap the Perl code in a loop. So there’s some bonus stuff there on the command line. But the Perl code itself is only 25 characters long, not a bad length for a program that displays the alphabet.

“Wheel On” in Downtown Buffalo

I’m here in Buffalo for the E-Poetry Festival at UB. Last night I got to present work downtown at the Sqeuaky Wheel, a media arts center that has been helping artists produce video, film, and digital work since 1985.

With my collaborator Stephanie Strickland, I presented “Sea and Spar Between,” our recent poetry generator which offers an unusual interface to about 225 trillion stanzas arranged in a lattice.

The full program for the evening included Alan Bigelow’s presentation of his “This Is Not a Poem,” which allows you to become a “treejay” and modify Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees”; a presentation of the voice-acted, distributed disaster narrative L.A. Flood project by Mark Marino; and a tribute to Millie Niss presented by her mother and collaborator, Martha Deed. These were followed by a very nice set of motion pictures, including, for instance, Ottar Ormstad’s “When,” featuring hulks of cars, the lowercase letter y, and the color yellow.

It was great to present with Stephanie in this context. Thanks particularly to Sandy Baldwin for introducing us and to Tammy McGovern at the Squeaky Wheel for hosting us.

Choose Your Own Monster

Since I mentioned some funny CYOA-like smut that has recently issued from the IF community, I’ll also suggest a less lewd piece of branching narrative, one which allows the reader to make choices early in the text and in the story’s past: Andrew Plotkin’s The Matter of the Monster. Perhaps it’s a case of the folktale wagging the dog – in any case, it’s brightly written, cleverly put together, and worth reading.

Take This Narrative Diction

I believe that Curveship and the example game Lost One may have just recieved their first roasting, thanks to the firepower of the S.S. Turgidity and the intrepid, enterprising player character Stiffy Makane. The “erotic adventures” that unfold in The Cavity of Time, released as part of the Indigo New Language Speed IF, allow you to jump everything within reach. And, just to be clear, to fuck all of those things. If you were offended just now, let me suggest that you don’t fire up this Choose-Your-Own-Adventure-style garden of fucking paths. Otherwise, this offering, written in the slick Undum system, may please you. Not like that. I mean it may amuse you.

Here’s a snippet from the beginning of the “Hip Curves” section:

The professor notices something about the device-shaped object.

That was immediately before a glass was refreshed.

The professor will be making a comment about focus.

A dial is being turned.

“Sorry about that,” he says. “What I was trying to say is that the tense shifts you are experiencing are the results of a local fluctuation in the field exerted by Hip Curves, my most diabolical erotic creation. Can I interest you in a mojito, by the way? There you go.”

I feel that in addition to commenting upon this reference, I must also invite you – if you are one of the non-offended – to plunge into the work in the question, if it doesn’t offend your morals. Please, drill Sam Kabo Ashwell’s Cavity.

“Indy” Text Adventures in the Eastern Bloc

Interactive fiction aficianados who aren’t at MiT7 (Media in Transition 7) and who thus missed Jaroslav Svelch’s excellent presentation – please check out the corresponding paper which he’s helpfully placed online: “Indiana Jones Fights the Communist Police: Text Adventures as a Transitional Media Form in the 1980s Czechoslovakia.”

Emulation as Game Facsimile (or Computer Edition?)

I’ve noted here at MiT7 (Media in Transition 7) that we’re now achieved some very reasoned discussion and understanding of the virtues of different approaches to preserving and accessing computer programs. Not that we’ve solved the underlying problem, of course, but I’ve been pleased to see how our overall approach has evolved.

Instead of simply dismissing emulation, migration, or the preservation of old hardware, we’ve had some good comments about the ways in which these different techniques have proven to work well and about what their limitations are. We saw this in the plenary discussion on archives and cultural memory late this morning – audio of that conversation will be coming online. Update: Here it is.

Clara Fernandez-Vara’s presentation “Emulation as a Tool to Study Videogame History” [Abstract] developed this discussion extremely well with regard to one important tool, the emulator. She presented the idea of a game in emulation as facsimile – not the original edition, but also not the Cliff Notes that we’d have to consult otherwise. She showed us a range of work with emulators that gives reserach, teaching, and casual access to older games, which would otherwise be neglected. Saving state, speeding games up, and even playing several of them at once with the same inputs are all facilitated by emulators.

Fernandez-Vara went on to note some limitations of emulation, such as that the physical controller, often significant to play, cannot be replicated in hardware; nor can particular hardware features such as those of the Dreamcast’s VMU or of a C64 floppy drive, which would whirr when something interesting was about to happen in a text adventure. Boxes and manuals are often very important and can’t always be effectively digitized; with online games and worlds, keeping the context is even harder. Finally, emulators have to be updated for new contemporary platforms every few years.

Much of the work of building emulators, Fernandez-Vara also noted, is done by fans who work as volunteers – institutional support can help them and can allow libraries to accumulate holdings. It would be nice if current platforms (the PS3!) were more backwards-compatible, too. “Abandonware” could be officially made available for use, to clear up legal questions.

The only thing I’d add to Fernandez-Vara’s excellent discussion is a slightly different framing perspective on the emulator. The emulated game may be usefully understood as a facsimile, but I see a different way to understand the emulator itself.

My suggestion is that an emulator can be conceptualized as an edition of a computer.

The first edition would be the original piece of hardware – for the Commodore 64, the August 1982 beige keyboard-with-CPU. Actually, in the case of the Commodore 64, even keeping to the United States there are at least three different “hardware” editions, since there are three ROM revisions, one used in very early machines, one in 1982 and 1983 computers, and one that was used in Commodore 64s and in the C64 mode of the Commodore 128. The three ROM revisions are not the only things that changed during the time the Commodore 64 was manufactured and sold, but they do change the behavior of the system. I suppose these better understood as being different “printings,” since the changes are limited to the ROM. That would be an interesting discussion to pursue. Either way, though, printing or edition, there are three different sets of hardware, three hardware Commodore 64s.

When the creators of VICE (the emulator I use) produce a program that operates like a Commodore 64, I understand this as being an edition of the Commodore 64. Yes, it’s a software edition. It isn’t an official or authorized edition – only being a product of Commodore would allow for that. (There are official, authorized emulators, but this is not one.) It’s not, of course, the original and canonical edition. But it’s nevertheless an attempt to produce a system that functions like a Commodore 64, one which took a great deal of effort and is effective in many ways. Thinking of this an edition of the system seems to be a useful way to frame emulation, as it allows me to compare editions and usefully understand differences and similarities.