From the Tables of My Memorie

Text from a well-known play, sorted in order but with many omissions, flits by repeatedly until someone holds down a button. As long as pressure is maintained, the screen displays one particular selection of one character's already-degraded lines. This allows visitors to read of forgetting and the loss of bodily form, and also to trace some material efforts that have been made to enhance memory, reaching from the dim history of the book into computing.

An interactive video installation presented in:

- More Human, Collision Collective 21

Boston Cyberarts Gallery, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, September 12-October 26, 2014. - International Conference on Digital Storytelling Exhibition

ArtScience Museum, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore, November 2-November 5, 2014.

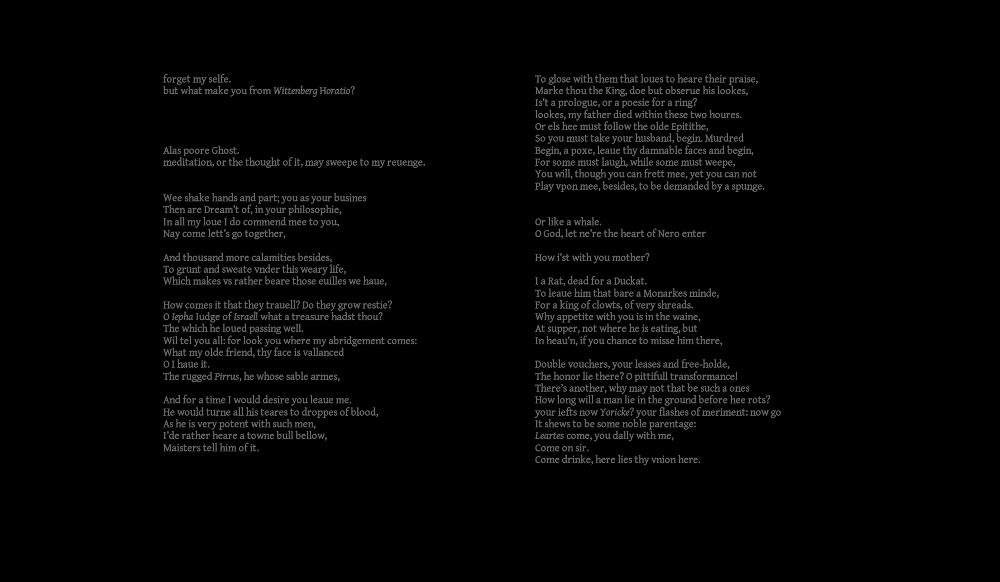

“From the Tables of My Memorie” uses as its source text part of the 1603 Quarto 1, or Bad Quarto, of Hamlet, and specifically is based on the lines to be spoken by Hamlet. Each text displayed consists of the random erasure of 966 of these 1032 lines (which includes blank lines, to indicate the break between speeches). The remaining 66 lines, which are kept in their original order, are shown.

The Bad Quarto is an example of forgetting. Scholars agree that it is a reconstruction of the play from memory by actors, principally the actor who played the minor part of Marcellus. The two colums of text are drawn only from Hamlet’s lines and are further reduced at random, using a simple method first employed in Montfort’s Python and Web piece “Through the Park” (also at nickm.com). In that work, a small number of sentences were written with the process of removal in mind, and the removal of texts was done on a sentence-by-sentence basis. In “From the Tables of My Memorie,” Shakepeare’s text is used without any alteration (except the alteration done in 1603) and is deleted a line at a time.

While the removal of text and the use of the Bad Quarto may make it difficult for those who are not Shakespearian scholars or actors to recognize the play, the Shakepearan language, the frequent references to Horatio, and the use of phrases that are highly memorable in global culture will signal something about the origin of this text to the reader, particularly if that reader considers a few screens closely. With effort, memory can prevail.

The careful reader will find Hamlet’s trajectory through the play represented in each screen. At the beginning, Hamlet greets and talks with Horatio; at least a few lines from this conversation will almost always appear. Other critical passages will also usually have at least a few lines to represent them: Hamlet encountering the ghost, speaking with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (called Rossencraft and Gilderstone in this text), talking with Ophelia, instructing the players, admonishing his mother and killing Polonius (called Corambis in this text), visiting the graveyard, and fencing with Laertes in the conclusion of the play. Hamlet will also proclaim parts of his famous soliloquies, although in the Bad Quarto they are shorter and the “To be or not to be” soliloquy occurs earlier.

Forgetting resulted in the Bad Quarto, and further algorithmic forgetting is used in “From the Tables of My Memorie,” but much persists despite all that has been misremembered and removed. The new configurations of text even have a sort of coherence and serve to characterize the speaker, particularly a speaker, such as Hamlet, who is metanoiac.

In this installation, erasures of Hamlet’s lines from the Bad Quarto cycle endlessly. The only way to hold a text fixed and read it is to hold the button down, which requires one’s presence and a good bit of effort. The would-be reader cannot simply look on, but must physically, materially commit by pressing and holding.